Six Nations: Are Eddie Jones and Owen Farrell the new Ferguson and Keane?

- Published

- comments

Eddie Jones is a lucky coach.

He is lucky with the talent he has in key positions, he is lucky with the funds and facilities created for him and he is lucky that no other nation save New Zealand has the same strength in depth sitting on their replacements' bench.

But there is nothing lucky at all about how he utilises all of those to forge an England team that has already set new records and may yet set more impressive ones still.

It wasn't hard to see where England were going wrong in the first half against France. It was everywhere you looked.

A first line-out so bad it hit the back of Dan Cole's head. A yellow card for a tackle that was unnecessary and illegal. An inability to dent the blue defensive wall with ball in hand, a problem stopping the waves of French runners coming at them from deep and wide and fast.

The difficulty lay in working out what to do about it and how to make that plan work.

No Vunipolas to add muscle and metres made. No Chris Robshaw to slow the progress of a French back row charging and offloading like a French back row of old. An opposition liberated from the stylistic straightjacket of recent torpid years, and a Twickenham crowd silenced by unexpected uncertainty and fear.

Any coach could have torn into their team after a first 40 minutes as scrambled as that. Not so many could have sent them out again after half-time clear of mind and confident in their ability to turn that slump into success. Fewer still could have made not just the right changes to personnel but customised the positional and tactical ones so shrewdly too.

With 18 minutes to go, England were much improved but still four points down, Rabah Slimani's offload-inspired try threatening to end France's 12-year wait for a win in south-west London and mark the Six Nations' opening day with a second shock to match that of Scotland's thrilling win over Ireland.

Off came Joe Launchbury. On came James Haskell into the back row, forward went Maro Itoje into the second row. More pace. More power.

Five minutes later, George Ford and Jonathan Joseph off, Ben Te'o and Jack Nowell on, Owen Farrell to fly-half, Elliot Daly to inside centre. More power still, now pace spilling out everywhere, now a dynamism and drive and the sound from the stands of belief and excitement too.

Quick ball, sharper minds. Farrell found Te'o, Te'o found a soft opposition shoulder and the try-line opened up in front of him.

Farrell a future captain?

Jones salutes 'ugly' England win

"I always thought we were going to win," said Jones afterwards. "I thought we were awful, but I always thought we were going to win."

There were not many others so sure in the moment, fewer yet who could have prevented even subconscious anxiety and anger from transmitting itself to the players on the pitch.

France had three men - Scott Spedding, Virimi Vakatawa and Louis Picamoles - who all made over 120 metres with ball in hand. Northampton number eight Picamoles, not content with being as hard and lumpy and slippery to stop as an iceberg, also carried the ball 15 times, beat seven defenders, made five tackles, offloaded four times and won a turnover too.

France made 591 metres to England's 383, made 10 line breaks to their opponents' five and beat 24 defenders to England's 13.

Those are hard numbers to turn your way.

Tough too was the blocking tackle Farrell put in on Picamoles as the number eight thundered into the England half with the game still in the balance, and harder still does it become with each passing performance not to see Farrell as not just Jones' epitome on the pitch but his skipper in waiting too.

Jamie George is putting his own pressure on Dylan Hartley, even if the incumbent captain and hooker is still understandably rusty after his most recent lengthy suspension. Farrell, four from five from the tee on Saturday, hitting the post with his other pot, is increasingly making an unarguable case either way.

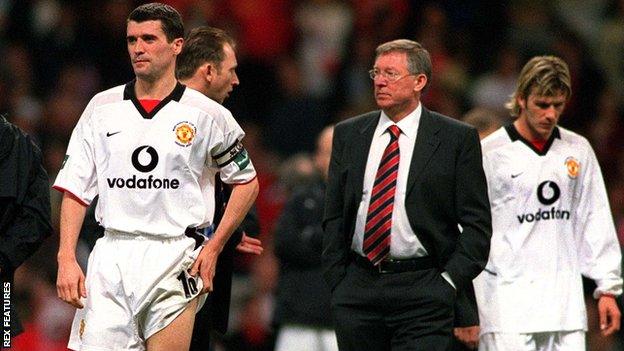

The best coaches have a leader on the pitch who shares their outlook, intensity and approach. Legendary Manchester United manager Sir Alex Ferguson had it best in outstanding midfielder Roy Keane: never a backward step, always pushing for better, intimidated by no-one and no situation.

Jones loves Hartley's obduracy. He appreciates his aggression, when it is focused and snarling just the right side of illegality.

Roy Keane captained Sir Alex Ferguson's Manchester United side to a historic treble in 1999

In Farrell's goal-kicking he sees a weapon that keeps better teams within reach and turns tight games his way. In the 25-year-old's youth he sees a man who will be at his physical peak at the next World Cup. In the apparent absence of self-doubt he sees a reflection of his own confident character.

Farrell is not as instinctive with ball in hand as his childhood friend and team-mate George Ford. He is not infallible with the boot, although he can sometimes make it look mighty close.

In a match like this, described afterwards by Jones as an ugly performance but a beautiful result, he is the backbone and the brains too: implacable, unshakeable, the on-field general who drags others along with him.

Jones isn't perfect. "I take full responsibility," he told the BBC on Saturday after the sub-par performance. "I didn't prepare them well enough."

Neither are his team, even if they have won more matches in a row - 15 - than any other England side in history. If he can solve problems, he must also be growing sick of the slow starts that cause them.

And he is certainly lucky. But so too are England, to have a coach who can take what he has been given and turn it into something better, who has set new standards and is still nowhere close to being satisfied.

More from rugby: |

|---|

Six Nations fixtures and Women's Six Nations fixtures |

For the latest rugby union news, follow @bbcrugbyunion, external on Twitter |

- Published4 February 2017

- Published4 February 2017

- Published4 February 2017

- Published4 February 2017

- Published1 February 2017

- Published17 March 2017