British and Irish Lions 2017: Six Lions wildcards to whet the appetite

- Published

- comments

The Lions won in Australia four years ago but face a huge task in New Zealand in June

On Tuesday, British and Irish Lions head coach Warren Gatland will sit down with his assistants and make his final selections for the 37-man squad to tour New Zealand.

Some of his decisions will be straightforward. Some will cause arguments. A few might even shock, for a Lions tour demands characters and skill-sets like no other, even if no-one should expect anything quite as eye-raising as the last time a Lions party was picked to meet the All Blacks, when Sir Clive Woodward also unveiled a specially commissioned pseudo-anthem called The Power of Four, with matching bracelets and lyric sheets for his players.

Historically, there has been no tougher place for a Lions team to tour than New Zealand; just six Test wins over 113 years, with 29 defeats. Great challenges require great selection. Should Gatland and his men require late inspiration, here are some of the most astute picks made by his predecessors over the past half a century.

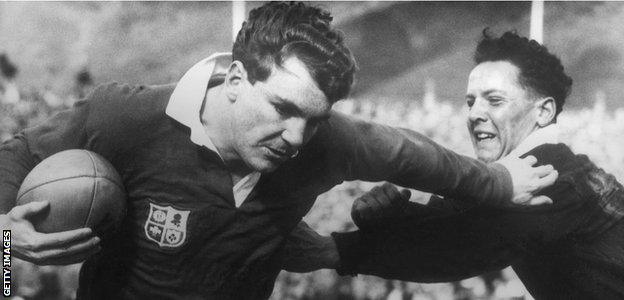

The tyro: Tony O'Reilly, 1955

Eighteen-year-olds and Lions tours should seldom go hand in hand, particularly when the destination is South Africa in the brutal mid-1950s and the itinerary is spread across three months. O'Reilly did not have much of a track record either - just five senior club appearances before being picked for Ireland, just four matches for his national side (three defeats and a draw).

What O'Reilly did have was precocious self-belief. And speed. And height. And a natural delight in the big stage and his own role upon it.

In future years his business empire would stretch from baked beans to newspapers to butter, zinc mines and fertiliser. On that tour he instead made hay, scoring two tries from the wing on his debut against a Northern Universities XV, bagging hat-tricks against the North Eastern Districts XV and Transvaal and starting all four Tests against the Springboks.

In the first, in front of 95,000 at Ellis Park in Johannesburg, he scored a try in the Lions' one-point defeat; as they won the fourth in Port Elizabeth to level the series at 2-2 he scored another.

That summer he would play a total of 15 games, scoring 16 tries. Four years later, in Australia and New Zealand, he played 23 and ran in 22 tries. As the 21-year-old George North would prove 54 years further on, age is less important on a Lions tour than the physical gifts that are beginning to blossom. And the chutzpah to make the most of them.

The back-row bolter: Peter Dixon, 1971

Dixon, a mobile and athletic back row forward, had been ignored by England's selectors for so long that he assumed his only involvement in the summer's tour to New Zealand would be reading about it in his newspaper two days after each match.

Coach Carwyn James, routinely ahead of the game, aware that to match the All Blacks he would need forwards with as much gas as they had grunt, thought otherwise.

In a team that boasted the attacking talents of Gareth Edwards, Barry John, Mike Gibson and JPR Williams, Dixon would go on to play three of the four Tests and score one of the most important tries of all.

After being rucked so badly in the second Test in Christchurch that he needed six stitches to the head, he returned for the fourth and decisive match at Eden Park in Auckland alongside Welsh Grand Slam winners Mervyn Davies and John Taylor to dive over for the only Lions try of the game.

It might not have been flashy - when the ball fell loose from a line-out, Dixon "just grabbed it and drove over," - but it set the platform for the draw that would seal the 2-1 series win, the only time the Lions have won a series in New Zealand.

Future Lions and World Cup-winning coach Graham Henry would later call that summer "the biggest wake-up call in New Zealand rugby history". Dixon, never the star, was a critical cog in that alarm clock. Kudos to Carwyn, as if the great innovator needed any more.

The second-string scrum-half: Brynmor Williams, 1977

John Dawes had captained that 1971 Lions tour and, having gone on to coach Wales before taking on the Lions job for their return to New Zealand, knew exactly what was required.

Which wasn't always what had worked for Wales, dominant though they had been in the Five Nations. Scrum-half Williams had never been capped by his national side when Dawes decided to take him to the other side of the world; his first appearance for Wales wouldn't come for another year, and his other two starts not until 1981.

Such were the issues that came with sharing eras with Gareth Edwards and Terry Holmes. But on that 1977 tour, Williams was outstanding in the narrow 16-12 defeat in the first Test in Wellington and the 13-9 win in Christchurch that levelled the series two weeks later.

In the third Test at the House of Pain in Dunedin it was Williams' break that set up Willie Duggan's first-half try and gave Dawes' men hope of a repeat of the triumph of six years earlier.

Instead, having torn his hamstring, Williams limped off early in the second half as the match and series slipped away. In his two and a half games, he had proved one of the old adages of Lions selection: it is not where you start in the pecking order that matters, but what you do to it.

The prince in waiting: Jeremy Guscott, 1989

Remarkable though it seems in retrospect - as well as at the time, when his form for Bath was so inspired - Guscott had not featured at all for England in their Five Nations campaign earlier that year. Neither was he initially selected for the Lions, but when England captain Will Carling withdrew with injury, coach Ian McGeechan decided he had seen all he needed.

The first Test had ended in a 30-12 defeat, their biggest ever on Australian soil. Guscott, along with Rob Andrew and Mike Teague, was among the critical changes McGeechan made for the second in Brisbane.

Guscott delivered immediately, cuffing a left-footed grubber through the Wallabies' defence before gathering the ball for the decisive try in a 19-12 win. When the final Test in Sydney was stolen 19-18, David Campese's fateful dally and dance and all, Guscott had become part of the only Lions team to come from a match down to win a series.

Eight years on, another swing of the boot - this time his a drop goal with his right - would seal another series win, the famous 2-1 triumph in South Africa. Having been a fly-half until the age of 19, perhaps that made sense.

So too did McGeechan's hunch. So confident and insouciant was Guscott, even before establishing himself with England, that he probably felt he should have been picked in the first place.

The professional: John Bentley, 1997

Bentley had faced his own battle with Carling, winning two caps for England aged 21 before realising that his face and background didn't fit with the national selectors in quite the same way as did the army officer from the private school.

He had gone off to play rugby league with Halifax and Leeds, before returning as part of the Rob Andrew revolution at Newcastle at the start of 1996. He played well that season, but it was in the second tier; aged 30, still nowhere near a recall with England, he was in few people's minds when McGeechan prepared to name his squad to play World Cup holders South Africa.

To McGeechan, as creative with his selections as he was as a fly-half and centre on the Lions tours of 1974 and 1977, Bentley's background was exactly what made him fit.

To beat the Springboks on their own turf he needed players who were fit, resilient and aggressive. His legion of league returnees - Allan Bateman, Alan Tait, Scott Quinnell, Scott Gibbs and Dai Young - would give him exactly that at a time when union in the northern hemisphere was still stumbling out of the faux-amateur era.

What McGeechan might not have envisaged was how much else Bentley would bring to the party. While his 70-metre try against Gauteng at Ellis Park and running battle with Springbok totem James Small against Western Province were unforgettable, so too were his contributions off the pitch - relentlessly upbeat, finding fun everywhere, the embodiment of the perfect Lions tourist.

The dasher: Jason Robinson, 2001

Robinson had a storied league career with Wigan, England and Great Britain before switching codes to join Sale, just seven months before the Lions tour to Australia.

While he had been picked three times for England in the 2001 Six Nations he had never started a rugby union Test and never scored an international union try. He was so convinced that he would not be picked by Lions coach Graham Henry that when the squad announcement was made he was in his back garden mending a fence.

Henry, helped by the counsel of his defence specialist Phil Larder, who had coached Robinson in the GB and England rugby league sides, believed when others did not. If Robinson could blow apart tightly organised league defences, he reasoned, he could do so if given ball and space in union.

So it proved. On his Lions debut Robinson ran in five tries against a weak Queensland President's XV; when the chance came in the first Test, with Wallabies full-back Chris Latham ahead of him and no space to work in at all, he swerved and skipped past just as he had so many times for Wigan.

Another try would follow in the third Test in Sydney. While the Lions would lose the tightest of series 2-1, Robinson would be back in Stadium Australia two years later to score England's only try in their World Cup final triumph.

Much of what Henry did on that tour came in for sustained criticism in the aftermath; his punt on Robinson never could.

- Published18 April 2017

- Published15 March 2017

- Published12 April 2017

- Published16 March 2017