'He was taller than me at 10' - meet the man who inspired Itoje

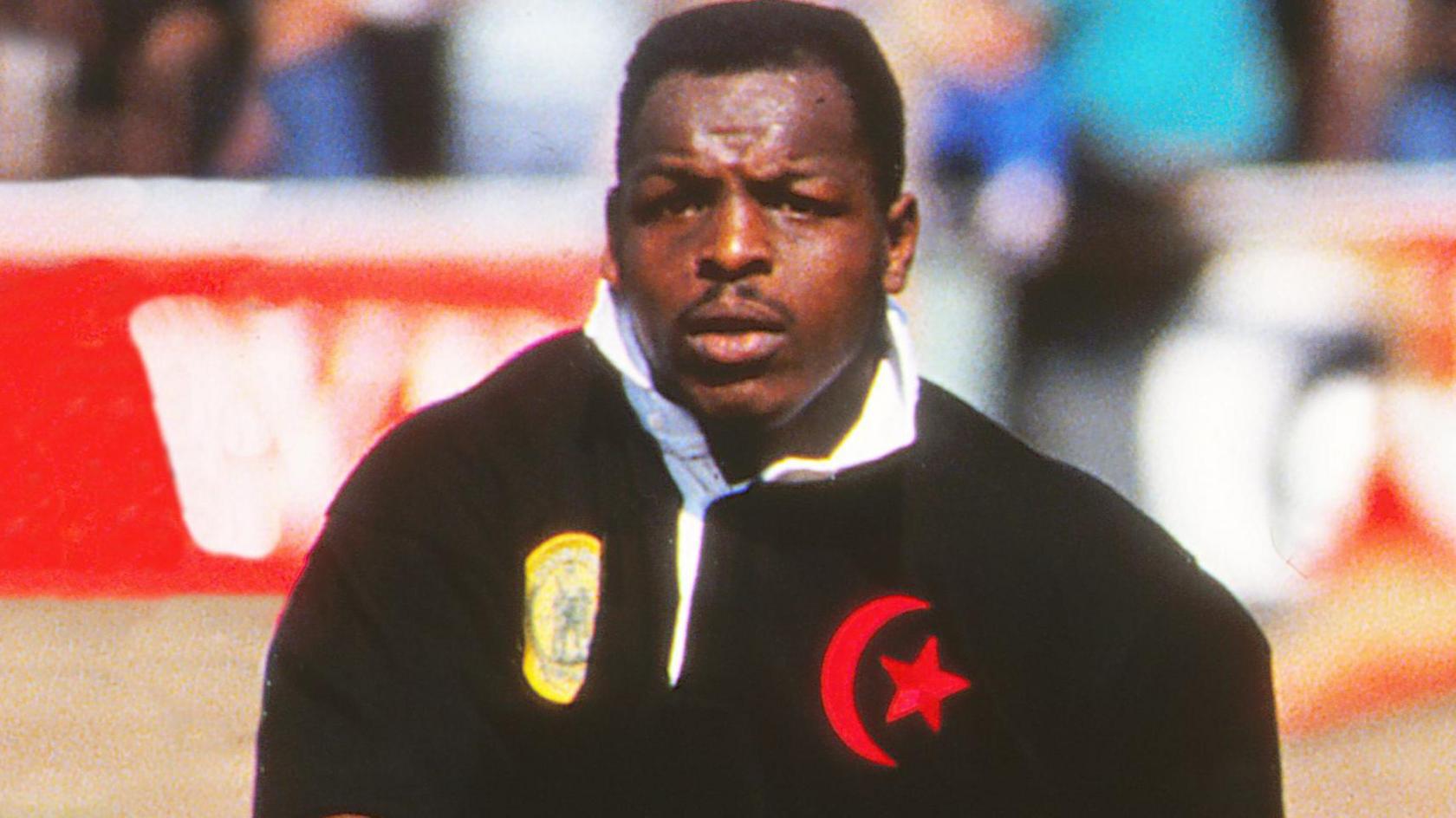

Floyd Steadman (left) was the first person to see Maro Itoje's potential as a rugby player

- Published

"When you hear stories of 10-year-olds running away, they'll run away for an hour or two and then they'll come back home. I stayed away from home on the run for nearly three weeks."

Floyd Steadman's story is one that some scriptwriters might say is too far-fetched.

Yet the man who first persuaded British and Irish Lions captain Maro Itoje to pick up a rugby ball has seen more in his 66 years than most - from poverty and abuse to being made an OBE, making rugby history and becoming a deputy Lord Lieutenant in his adopted home county of Cornwall.

Itoje to face Brumbies as Test team appears to form

- Published7 July

I was brash and naive in 2017, now I'm ready - Itoje

- Published9 May

British and Irish Lions fixtures for tour of Australia

- Published2 August

"My parents were part of the Windrush generation," Steadman explains.

"They came over in 1956 and I do remind people why a lot of those immigrants came from the Caribbean, from the countries of South Asia from East and West Africa.

"They answered the call to help rebuild the motherland after the destruction of the Second World War."

But while his family and migrants like them suffered racism and discrimination, Steadman suffered at home as well.

His mother walked out on his abusive father when he was just one year old, and years later Steadman would do the same - unable to take any more of the beatings and neglect he was subjected to.

Sleeping in a neighbour’s shed or a local park, 10-year-old Steadman had to become streetwise very quickly.

"I got a job on a milk round where they paid me in old money seven and six a day, that's about 36 or 37 pence,” he says.

"But it meant I could finish my milk round, go to the cafe, get a big-boy's breakfast and have enough money for a packet of biscuits later in the day.

"I survived like this on the run, a feral child in north-west London, for the best part of three weeks."

When he was eventually brought home by a policeman and a social worker after being taken in by one of his teachers, his father rejected him.

"The policeman knocks on the door, my father opens the door and the look of disgust my own father gave me," Steadman recalls.

"He turned to the policeman and said 'I don't want him back, take him away' - I was 10 years old and I was taken into care.

"So I then spent seven years in children's homes."

Floyd Steadman says there were few players like him when he was growing up

Growing up in care Steadman forged a love for rugby - starting out as a hooker, then a back row, before becoming a full-back as he was quick and could tackle.

But it was when he switched to scrum-half that it clicked - his school side became unbeatable and Steadman was called up to his county team and had trials for England schoolboys, though injury meant he never made the national side.

He was picked up by Saracens and went on to be their first black captain as players such as Mike Wedderburn, Chris Oti, Victor Ubogu, Steve Ojomoh and Jeremy Guscott became some of the first black stars of English rugby.

But for Steadman, while these players were great role models as forwards and backs, there were no black scrum-halves - other than him.

"This is a challenge that I ask every rugby player - you've got to name me another English-born black scrum-half that's played elite rugby at Premiership level. I don't think there is," he says.

"In today's age, where there are so many talented youngsters of all shades, there must be some brown and black boys and girls that are talented enough to play scrum-half.

"Partly I think because where are the role models for them? When I was a young rugby player my role model - and I don't mind telling you - was Gareth Edwards, the king of scrum-halves.

"My black role models as a boy were Muhammad Ali and Pele, two iconic sporting figures that probably transcended sport, and my all-time role model when I was growing up was Nelson Mandela."

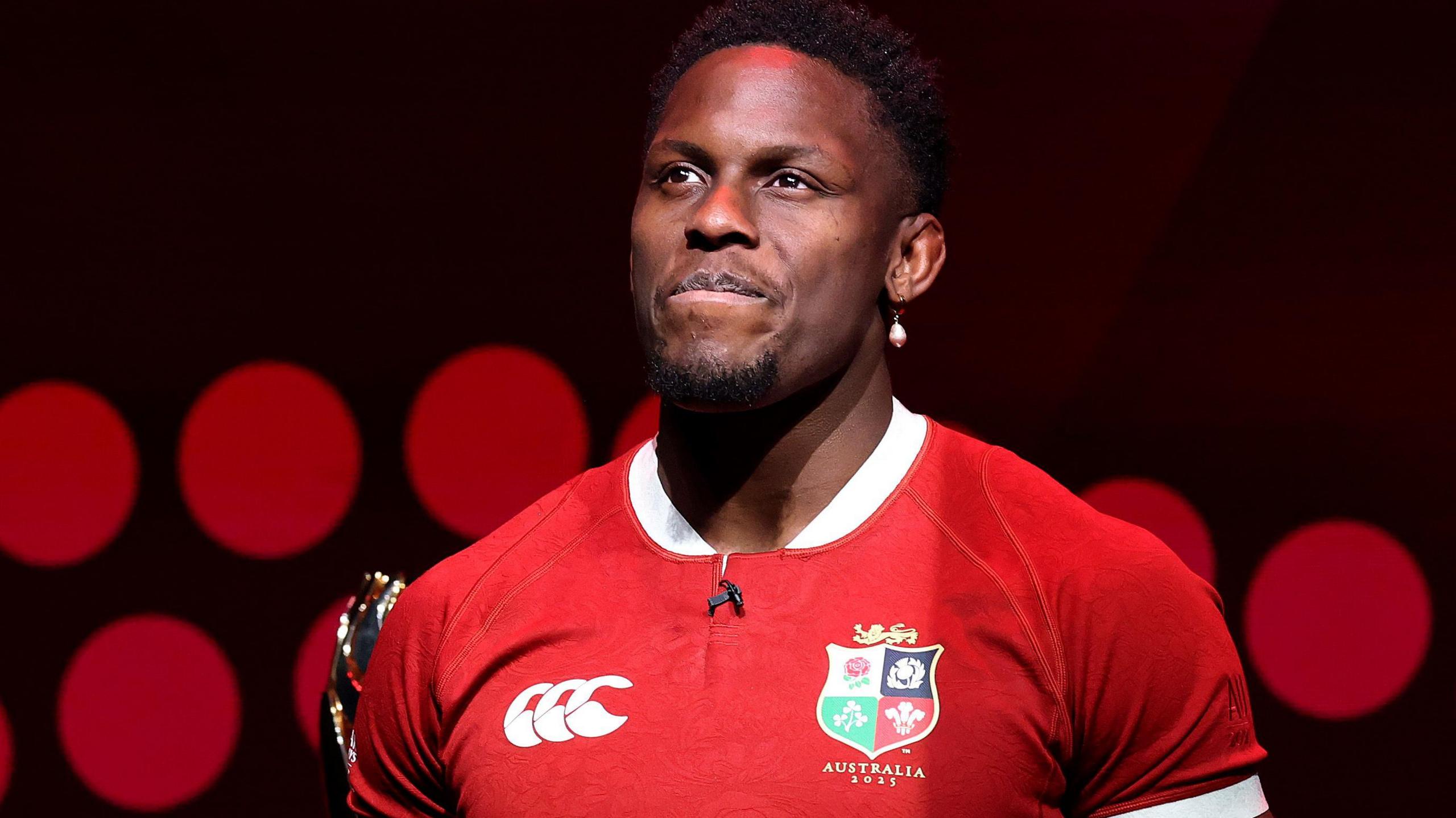

Maro Itoje will be the first England captain of the British and Irish Lions since Martin Johnson in 2001

While Steadman may not have had many role models when he was a young player, he was determined to become one himself.

After becoming a teacher he rose through the ranks and became headteacher at a number of prep schools - including Salcombe in south London.

It was there he first came across a young Itoje.

"From day one I remember seeing this 10-year-old black boy at my new school who was imposing, because physically he was big - he was taller than me and he was 10," remembers Steadman, who was awarded an OBE for services to rugby, education and charity in the 2023 New Year Honours.

"Normally he would have a basketball in his hand or a tennis racket or a football.

"Whatever he tried he was just outstanding, and one day I remember going over and saying 'Maro you should try this game rugby, you're built for rugby, you'd be good'.

"His eyes glazed over, but that evening I rang his father and said 'Mr Itoje, your son could be a very good rugby player, I suggest that in his senior school he starts playing rugby and please take him to Saracens, because Saracens will look after him'.

"I'm pleased to say that Mr Itoje listened to me, and although I didn't realise, Maro was listening because when he went to his senior school he did start playing rugby."

The rest, as they say, is history.

Itoje has gone on to earn 93 England caps, win five Premiership titles and three European Champions Cups with Saracens, and will captain the Lions on his third tour this summer - a role Steadman feels is perfectly suited to his former student.

"You're going to see someone that is very mature, very articulate," he says.

"I think he's learnt how to work the referees, unlike us chirpy scrum-halves.

"I've watched him this year and he's certainly at the crucial time just been there listening, just a subtle word in the ear and I congratulate him for doing that.

"I think he's incredibly fortunate to lead what looks like a very exciting squad for the British and Irish Lions."