Andy Murray: The making of a British sporting hero

- Published

- comments

Just imagine, just for a second, what it must have felt like for Andy Murray.

Leading in the final of the biggest tennis tournament in the world and on the verge of ending Britain's 77-year wait for a men's singles champion at Wimbledon.

And yet break point down, serving for the championship. Against Novak Djokovic, the best player in the world and famous for his comebacks. Having had three match points.

Don't know about you, but I'd be shaking so much I wouldn't be able to keep a single ball in play. I'm surprised Murray didn't serve underarm.

Thinking about it now - 48 hours on - it's still quite chilling.

While we get swept along by smart suits and talk of knighthoods, I think it's important to revisit those few incredible points on Centre Court at the All England Club to remind ourselves what happened, what Murray achieved.

Advantage Djokovic. At that point, the Serb was smirking to the crowd and nodding, suggesting he was still confident of victory against the British favourite, as if to say: "We're going to be out here for another three hours and I'm going to have you in five."

But Murray denied Djokovic a second Wimbledon title, winning that extraordinary 10th game of the third set to demonstrate his brilliance, his determination and his will to win.

The 24 hours that followed were chaotic to say the least. Murray immediately carried out a succession of television interviews, from Sue Barker at the BBC to our friends at Wow Wow in Japan, who seemed as excited as they would have been if one of their own had triumphed.

When he arrived in our little radio room half-an-hour later, he slumped into a chair and, after checking someone was getting him some sushi, muttered that he didn't want to leave because he was "so, so tired".

But sleep wouldn't happen for many hours yet. After more interviews, it was off to a plush Mayfair hotel for the Champions' Dinner.

He appeared at almost midnight, decked out in dinner jacket and bow tie, posing with the trophy, teasing Andrew Castle and looking chuffed to be there.

His magnificent support team also posed with pride, while Ivan Lendl actually smiled. In fact, I didn't see him stop smiling. Having reached two Wimbledon finals and never been victorious, Lendl has played a considerable part in Murray's success since joining the Scot's camp 18 months ago.

Likewise, Dani Vallverdu, the softly spoken Venezuelan, Murray's friend from academy days in Spain, whose influence is underestimated. Plus physical trainers Jez Green and Matt Little, physio Johan De Beer and Rob Stewart who keeps every part of Murray's life in order.

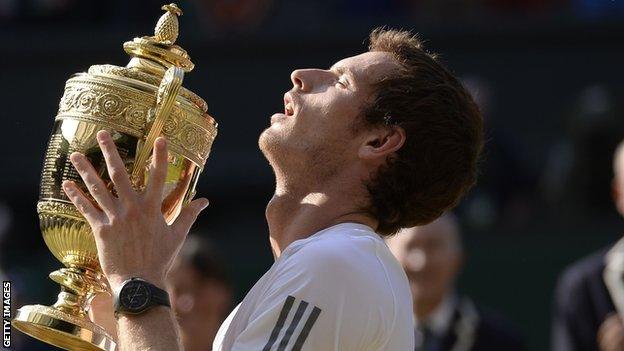

Andy Murray defeated world number one Novak Djokovic 6-4 7-5 6-4 to lift the Wimbledon trophy

A thought also for former physio Andy Ireland, who cut down on his work with Murray this year for personal reasons.

Without these guys, Murray would not be the man he is.

After one-and-a-half hour's sleep, a car bowled up outside Murray's house in Surrey to whisk him back to Wimbledon for breakfast interviews on Monday morning.

The place was deserted and had an eerie atmosphere as we waited to greet the champion. He ended up doing upwards of 30 interviews, from The Today Programme to Chris Evans, This Morning to Breakfast in America.

It was tiring, some of the chats perhaps an imposition too far, but amazing exposure for tennis.

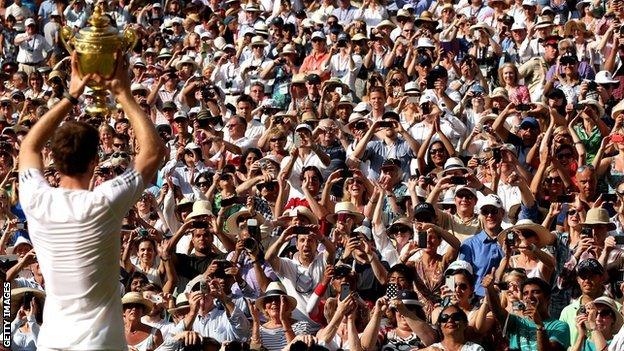

The moment Murray won Wimbledon

Then, via a sponsorship event in south London, to Downing Street and a meeting with Prime Minister David Cameron. Murray's wave to photographers may have been sheepish but when he stood there outside Number 10, thumbs in pockets, he looked like he owned the country.

When I think back to 2004 and the first time I met him, juggling tennis balls on both feet in a sports hall in Luxembourg, perhaps we should have known. He spent that Davis Cup weekend bending the ear of Tim Henman and Greg Rusedski, listening and learning.

Later that year, at the BBC's Sports Personality of the Year awards ceremony, he collared Sir Clive Woodward for the inside track on England's 2003 World Cup win., external He was young and naive but even then I knew he would be a star. He just seemed so sure of himself.

The following year, 2005, witnessed his breakthrough on the main ATP tour. A debut match in Barcelona was followed by his first wins at Queens and a three-set challenge to Grand Slam winner Thomas Johansson. Despite ending the match with a horrific bout of cramp, Murray's display marked him out as one to watch.

And so it proved at Wimbledon that summer. Radio 5 live sent Tony Adamson, one of my great broadcasting heroes, out to the old Court 2 to cover Murray's opening match with George Bastl., external

Little did I suspect that Tony, on match point, would get a little carried away. "Mark my words," said Tony. "This is a future Wimbledon champion!"

Andy Murray enjoyed an afternoon with the Prime Minister following his victory

Relatively fresh into the job of tennis correspondent for 5 live, I remember dampening expectations by insisting it was way too early to suggest Murray was destined to triumph at the All England Club.

I'm sorry Tony, we really should have believed you there and then.

A straight-sets victory over Radek Stepanek in round two, external was the first time I remember getting really excited about watching Murray.

I did that match, on Court 1, with former Wimbledon champions Michael Stich and Tracy Austin. They laughed when I overdid it in my commentary but, boy, were they impressed.

That was the day I knew Murray was heading for the top 10.

As 2005 progressed, it was refreshing to get to know young Andy a little more. Already aware of his anti-establishment leanings, I thought it was great for tennis in Britain, after the Henman years, to have someone a little brasher, a little more outspoken.

When he qualified for the US Open that August, he celebrated by putting his finger to his mouth in a sshh-style gesture much like Jose Mourinho.

We were on Court 46 at the time and there were not too many people in the small stand. It seemed a really strange thing to do.

Dunblane residents took to the streets to celebrate Andy Murray's victory

I chased him off court and down a corridor. When I caught up with him, he ranted into my microphone against those who suggested he was not fit enough. Still angry, Wimbledon's officials were his next target, complaining they should have done more to get him into the main draw at Flushing Meadows without the need to qualify.

All this after just winning a match…

He went on to beat Andre Pavel in the first round of the US Open,, external despite being violently ill on court. If stamina was in question, he had just provided a defiant response.

It was clear by this point that the media was going to play a huge role in the development of Murray, both as a tennis player and as a man.

When he lost in the first round of the Australian Open in 2006, he blamed the assembled journalists for putting too much pressure on him.

We watched the Champions League final in a Hamburg restaurant that May. As Barcelona beat Arsenal, external on the big screen, we talked about the media and this strange, all-consuming world he had been catapulted into. Over burgers, fries and lemonade, he was fascinating company and remains so.

Andy Murray talks to BBC Breakfast after historic Wimbledon win

The match that made me upgrade my "top 10" prediction to "potential Grand Slam champion" was the contest against Rafael Nadal in Australia in 2007., external The Spaniard won in five sets but Murray took the initiative, adapting his normal game for the challenge of playing a big star and almost won.

After the match, I got annoyed with a former colleague, who, despite the brilliant effort, kept ramming home the point that Murray had not won.

One day, Murray is a world beater; the next, he's a loser. Some people seem to think nothing exists in between.

Developing as a player but with so much still to learn off the court, those years in his early 20s were not easy for Murray.

His early coaches suggested the gym wasn't his favourite place and he needed to learn that the hard yards would benefit him long term. There were also claims he didn't like playing early in the morning because he liked his sleep too much. He lost a few silly matches, including some at Grand Slams, as a result.

Again, he did not like the criticism, but, on reflection, I'm sure accepts it was constructive.

He continues to improve as a person and a player every day.

And now, in the face of huge public pressure and an ever-decreasing minority of haters, he has conquered Wimbledon. It really is a boy's own story of hard work, achievement and inspiration.

- Published8 July 2013

- Published8 July 2013

- Published8 July 2013

- Published8 July 2013

- Published7 July 2013

- Published7 July 2013

- Published8 July 2013

- Published7 July 2013

- Attribution

- Published8 July 2013