American law: How non-US companies are affected

- Published

Should the US operate as a global sheriff?

Does the US have a legitimate right to intervene in the behaviour of companies and individuals, or indeed of countries, operating beyond its own borders?

The question is pertinent and timely, given that Standard Chartered, a UK bank, was accused this week of violating US law.

Not, that is, as a result of the bank's relatively limited activities in America.

Rather, the bank stands accused of hiding transactions for "Iranian financial institutions" that were subject to US economic sanctions. The bank denies the allegations.

US link

The case is just the latest example of how the US has been extending its so-called extraterritorial powers in recent years - where the US has been flexing its legal muscle outside its own territory.

"The issue boils down to the following concept," says Jacob Frenkel, chair of securities enforcement, white-collar crime and government investigations practice with the law firm Shulman, Rogers, Gandal, Pordy & Ecker.

"Any sovereign, whether a country, province, state or municipality, has a right to expect that a company or person doing business in that territory is subject to the laws of that territory.

"Just as a party doing business enjoys the protection of the laws, so too must a party comply with the laws."

That definition raises two further questions. First, how should "doing business in that territory" be defined? In other words, when is an individual or firm deemed to be doing business in the US?

It does not take much, according to David Pitofsky, a member of law firm Goodwin Procter's litigation department, who is currently involved in client work connected to the Libor scandal, and is representing the administrator of the Gulf Coast Claims Facility, which deals with claims from victims of the Deep Water Horizon oil spill.

"As long as dollars are involved, they will eventually touch a US institution," he says, referring to how almost all banking transactions, particularly in US dollars, will at some point in the process flow through the Federal Reserve Bank in New York.

The courts have made clear over the years that such flows of funds through New York is sufficient for asserting jurisdiction.

"Even if a transaction is done, say, in Japanese yen, if a blip in the system turns these into dollars - however briefly - that in theory could mean it falls under US law," says Mr Pitofsky.

Global patents

The US dollar is widely used in international business transactions

American patent lawyers are also eagerly eyeing activities abroad.

"Through both judicial and legislative efforts, [US patent law] has evolved from a strict territorial based set of laws asserting jurisdiction only over those infringements taking place on American soil," according to University of Alberta professors Moin Yahya and Cameron Hutchison.

US patent law, they say, has expanded into "a more expansive set of rules asserting jurisdiction over any event that may harm patent holders in the United States regardless of where the infringement is taking place".

"This, we argue, is contrary to the original purpose of patent law and inconsistent with American obligations under the International Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property," they write in a paper, external.

The Dodd-Frank Act

Another example of how the US legal system is extending its tentacles abroad is the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, external, a controversial piece of legislation that provides for extraterritorial jurisdiction for US courts over actions brought where US investors or markets are harmed by actions outside the United States.

Dodd-Frank, with its numerous registration and clearing requirements and its ongoing revisions, has caused considerable legislative uncertainty in a number of financial markets.

The act has resulted in particular concern among players in the so-called over-the-counter derivatives markets, which include interest-rate, currency or commodity swaps that are used by companies in a wide range of sectors to reduce investment, currency and trading risk.

"We have a rule that's being extended beyond its original scope, and that's concerning," says Don Thompson, managing director and associate general counsel at JP Morgan in New York.

Corruption outside the US

The second question raised by Mr Frenkel's definition of what the issue relates to is should non-US individuals and companies be bound by US law even when they operate outside the US, simply because they also do some business in America?

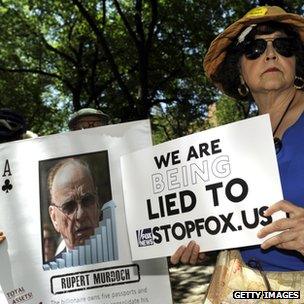

The behaviour of Rupert Murdoch's media operations in the UK brought him unwanted attention in the US

According to US anti-corruption laws, they should.

Two examples illustrate how such laws are increasingly used to target activities that take place in other parts of the world.

The media tycoon Rupert Murdoch's US-based global media group News Corporation is co-operating with the US Department of Justice (DoJ) which is looking into possible breaches of the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

The DoJ is examining allegations its now defunct UK newspaper subsidiary News of the World paid UK officials for information, something prohibited by the Act.

In 2010, industrial group Daimler, the owner of Mercedes-Benz, pleaded guilty in the US to corruption charges after admitting to paying tens of millions of dollars in bribes, external to government officials in at least 22 countries. The bribes were not paid in the US, yet the German company agreed to pay US authorities $185m (£118m) to settle the case.

Similarly, back in 2008 the German industrial group Siemens paid $800m to settle a US investigation into bribes paid to government officials in Argentina, Bangladesh, Iraq and Venezuela.

Extradition to the US

Individuals have also been targeted.

In 2009, Gary Kaplan, the boss of London-based gambling company BetOnSports, fell foul of a US law that bans Americans from placing bets online, external even on websites outside the US. He was jailed for four years.

In 2006, three British former NatWest bankers were extradited to the US to face fraud charges, in a case sparking anger in the UK business community, external.

At the time, the bankers said their crimes had taken place in the UK and the victim was a UK bank hence they wanted to be tried in Britain. But the US authorities said their actions had been linked to the collapse of the energy giant Enron and as such it was a US matter.

And earlier this year, retired UK businessman Christopher Tappin was extradited to the US on charges of exporting parts for Iranian missiles.

In fact, the US is tightening its sanctions against Iran, and thus the potential for legal action against anyone trading with the country - and not just those doing deals that would aid it in building a nuclear reactor.

Earlier this month, US Congress voted to impose sanctions that meant anyone who provided commercial goods, technology or financial services to Iran's energy sector could face punishment.

Regulatory bodies

Critics of the international reach of US legislation do not necessarily disagree with US ambitions, which range from protecting the global financial system to curbing the nuclear or military ambitions of a number of dictatorships.

But companies, whether in the financial services sector or in industry or elsewhere, do object to the one-sided approach of US legislation, pointing to a lack of reciprocity that would allow other countries' legal systems to also cover US firms.

That, however, is "an issue for the 'affected' sovereign", according to Mr Frenkel.

"There is nothing that prevents other sovereigns from adopting laws and courts of other sovereigns from enforcing laws as sweeping and with the breadth of US enforcement programs. That becomes an issue of sovereign willpower and allocation of enforcement resources."

Non-US critics have also vented their anger in instances where they deem US rulings unfair.

And many complain about the increased complexity of doing business, both within and outside the US.

The thicket of new regulations has the potential to create an uneven playing field in international markets, according to Dan Cohen, managing director and head of government relations for the Depository Trust and Clearing Corp, a non-commercial co-operative that serves as the primary post-trade infrastructure organisation for US capital markets.

Moreover, it could impede global regulatory co-operation and undermine efforts to increase market transparency and mitigate risk in the over-the-counter derivatives market, he says.

Others point to the added complexities for companies required to deal with the vast and growing number of regulatory bodies in the US.

Not only will they have to comply with the rules of federal bodies such as the US Securities and Exchange Commission, the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, there are also state bodies, such as The New York State Department of Financial Services, which is the regulator that accused Standard Chartered.

It is 10 months old and supervises some 4,500 institutions with assets of about $6.2 trillion.

Yet many had not even heard of it until this week.

- Published8 August 2012

- Published10 December 2012

- Published10 April 2012