Northern Ireland: Did anyone warn about Brexit checks?

- Published

The UK is seeking to change the Brexit deal for Northern Ireland - known as the protocol - because it says it is affecting trade, businesses and has led to a 'brewing political crisis'.

The protocol, part of the December 2019 deal that took the UK out of the EU, keeps Northern Ireland following many of the rules of the EU single market.

Since it came into force at the start of 2021, it has created checks on goods moving from Great Britain into Northern Ireland, and other border bureaucracy, which many loyalists bitterly oppose.

The EU is also looking at ways to address the growing tensions.

But what was said about Northern Ireland in the run-up to the 2016 EU referendum, and how many of these issues were predicted at the time?

Referendum campaign

The main campaign literature published by the Leave and Remain campaigns on a UK-wide basis in 2016 didn't mention it at all.

Leading figures on both sides made campaign visits to Northern Ireland, but its future status wasn't a big part of the national conversation.

It was only after the vote took place that more attention was paid to the fact that the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland was about to become the border between the UK and the EU.

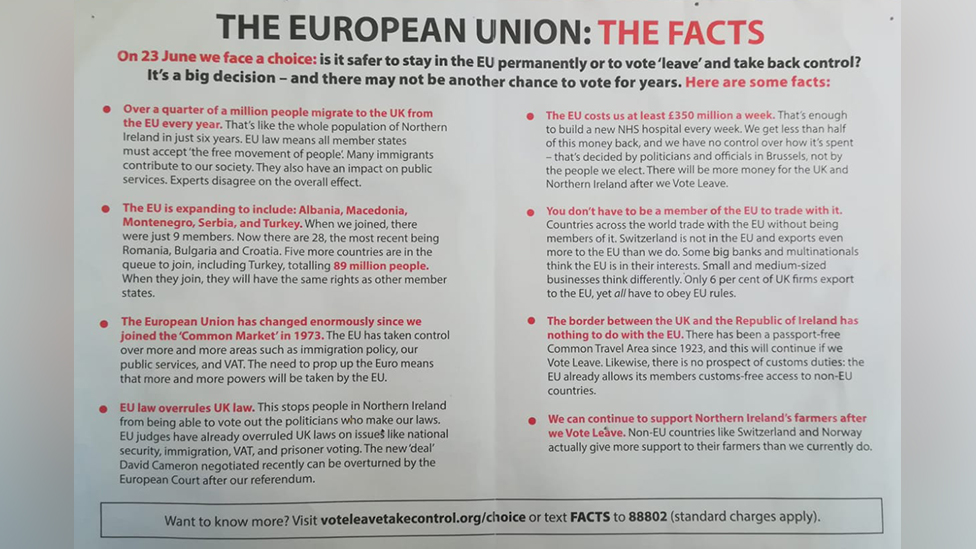

Even in campaign leaflets aimed specifically at Northern Ireland, which did at least mention the border issue, Leave focused first on immigration and ending free movement, while Remain emphasised protecting jobs.

Sinn Fein did use the slogan "Brexit means borders", and on a visit to Northern Ireland in June 2016, the then Chancellor George Osborne said there would have to be a hardening of the border, if the UK was outside the EU.

It raised the prospect of checks and even checkpoints returning to the border with the Republic, which the Northern Ireland peace process had removed.

That didn't happen because divorce negotiations between the UK and the EU agreed early on that avoiding a hard land border should be an absolute priority.

"For all the talk of 'taking back control' of borders," says Prof Katy Hayward of Queen's University, Belfast, "the overwhelming sentiment across the spectrum in Northern Ireland during the 2016 referendum was that there should not be any change to its borders."

What about a border in the Irish Sea?

Everyone assumed the only border up for discussion was the land border with the Republic. There was virtually no mention of what has emerged instead - border checks and bureaucracy between Great Britain and Northern Ireland - the so-called Irish Sea border.

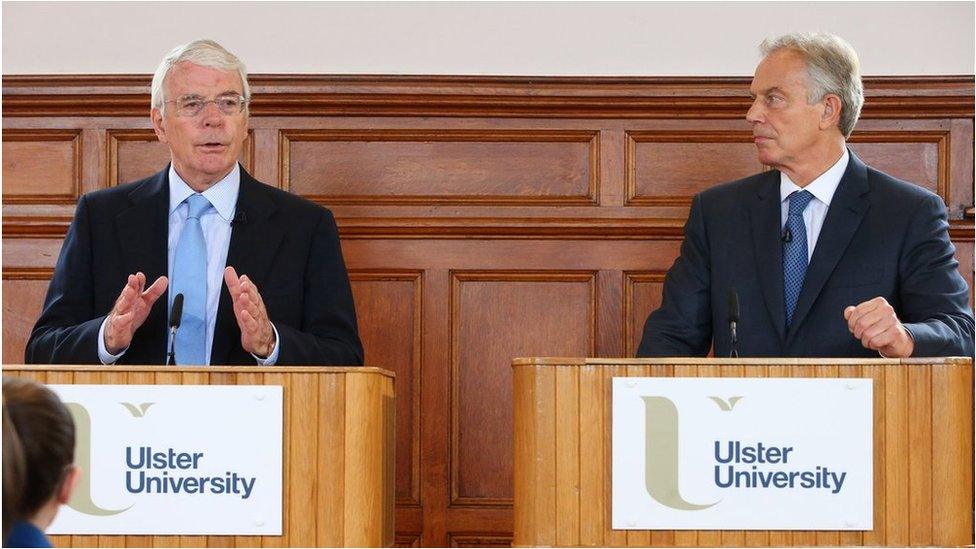

The prospect of this happening was briefly discussed during a visit to Londonderry on 9 June by two former prime ministers - Sir John Major and Tony Blair. Both were strong supporters of Remain.

Mr Blair argued a vote to leave would mean the only alternative to controls on the land border "would have to be checks between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, which would be plainly unacceptable as well".

Sir John warned it would be "an historic mistake" to do anything that risked destabilising the Good Friday Agreement, which brought the troubles in Northern Ireland to an end.

In response, the then Northern Ireland First Minister Arlene Foster spoke of "deeply offensive" scare stories from the Remain campaign, and the then Northern Ireland Secretary, Theresa Villiers, also a prominent leave supporter, said any suggestion that Brexit could have a negative impact on the peace process was "deeply irresponsible".

At the time, it was not clear what form of Brexit might emerge after a leave vote. Many people on both sides thought the UK could choose to remain in the EU single market (like Norway) while leaving the EU's political structures.

Confused by Brexit jargon? Reality Check unpacks the basics.

But the government pursued a different path. And with Britain outside the single market and the customs union, some border bureaucracy had to be introduced between GB and NI instead.

Referendum claims

Voters were never really told that this could happen, nor were they given a particularly accurate picture in referendum leaflets about how trade and borders operate.

The Remain campaign said "a vote to leave would result in tariffs being imposed", which would "push prices up". But under the new EU-UK free trade deal there are currently no tariffs (taxes on imports) on goods that originate in either the EU or the UK.

The Leave campaign said customs wouldn't be a problem, because "the EU already allows its members customs-free access to non-EU countries." That is only true for countries that are in the EU customs union. For Britain, it is incorrect.

Common Travel Area

Leading Remain supporters also warned of a threat to the Common Travel Area, external (CTA) between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

"The leave people say it will just stay," Mr Blair said. "But when you go into the detail you realise how difficult if not impossible that is."

A few days before the referendum, David Cameron also briefly raised the prospect that preserving the CTA, with Britain outside the EU, could lead to "some sort of checks" on people travelling from Northern Ireland to the rest of the UK.

These warnings were incorrect. The CTA, which was founded before both the UK and the Republic of Ireland joined the EU, survived Brexit unscathed.

Its importance had been emphasised earlier in 2016 by Boris Johnson, shortly after he declared allegiance to the Leave campaign.

"There's been a free travel area between the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland for, I think, getting on for 100 years," he said.

"There's no reason at all why that should cease to be the case."

The CTA was protected because of the joint determination to avoid a hard land border.

But as prime minister, it was Boris Johnson who signed up instead to the deal creating new border bureaucracy for trade between GB and NI.

And many loyalists now feel that pushes them further apart from the rest of the UK.

This piece was first published on 19 April and updated to add David Cameron's comment about the Common Travel Area.