How much market chaos did the mini-budget cause?

- Published

New Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has reversed almost all of the tax measures outlined by his predecessor Kwasi Kwarteng three weeks ago.

The mini-budget of 23 September - included £45bn of unfunded tax cuts - and was followed by days of turmoil on the markets, a fall in the value of the pound and rises in the cost of UK government borrowing and mortgage rates.

Prime Minister Liz Truss subsequently sacked Mr Kwarteng and acknowledged that "it is clear that parts of our mini-budget went further and faster than markets were expecting".

Previously, Ms Truss, Mr Kwarteng, Business Secretary Jacob Rees-Mogg and other ministers had defended the mini-budget, focusing on the effect of global factors like rising inflation and interest rates rather than acknowledging that the 23 September announcement had a profound impact.

So, what has been going on?

Global interest rates

It is true that interest rates have been rising around the world as central banks, including the Bank of England (BoE), try to control inflation, made worse by Russia's invasion of Ukraine and the energy price shock which followed.

On 22 September, the BoE announced it was increasing the UK's base rate by 0.5 percentage points, to 2.25%. This is the interest rate on which commercial banks base the amount you pay for borrowing money, and what banks pay you for saving money with them.

The day before, the US central bank had raised its interest rates by more - 0.75 percentage points to between 3% and 3.25%.

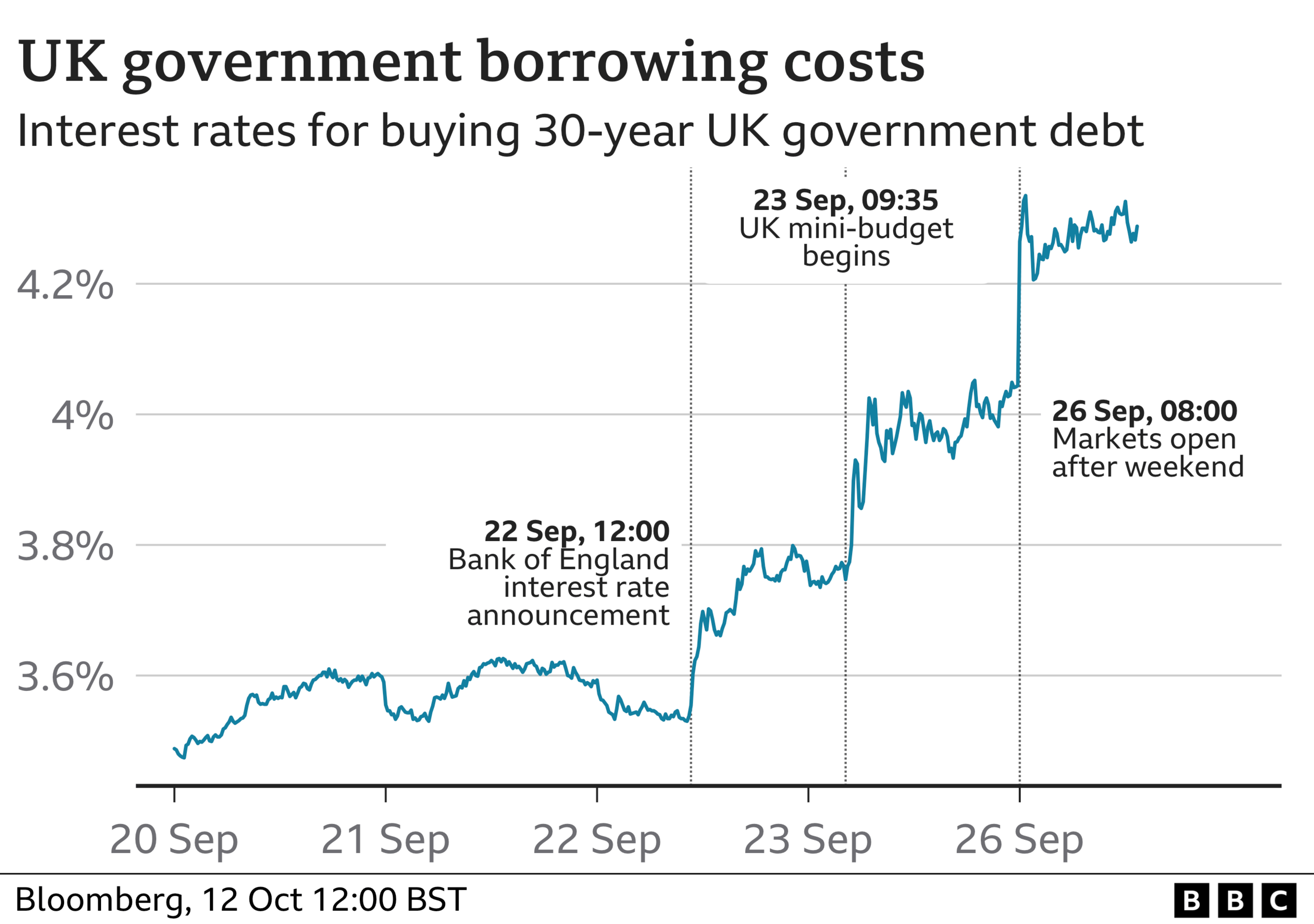

Following the BoE's decision, the UK government's long-term borrowing costs - the interest rate the government has to pay to borrow money on the international markets - rose immediately. By the BoE's own analysis, long-term gilt yields were 0.2 percentage points higher at the end of the day as compared with the start.

Government's mini-budget

The next day - 23 September - Mr Kwarteng delivered his mini-budget starting at 09:35 BST.

This included the government's support scheme for energy bills - which had already been announced. This was due to last two years for households and the Treasury estimated it would cost £60bn for the first six months.

It also included a cut in National Insurance and the reversal of a planned rise in corporation tax. These tax changes were pledged by Ms Truss during her Conservative leadership campaign and were widely expected to happen.

But Mr Kwarteng went further, announcing he would cut the basic rate of income tax a year earlier than expected and get rid of the top rate altogether.

The package of tax cuts announced in the mini-budget totalled £45bn and were unfunded in that the government did not set out what savings it might make.

The mini-budget was not accompanied by an assessment of its plans by the government's official spending watchdog - the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) - as happens at every budget.

Following the chancellor's statement, the UK government's cost of long-term borrowing rose sharply. According to the BoE, long-term gilt yields rose 0.3 percentage points over the course of the day.

The markets were closed over the weekend, but in a BBC interview on Sunday 25 September, Mr Kwarteng indicated there were more tax cuts to come.

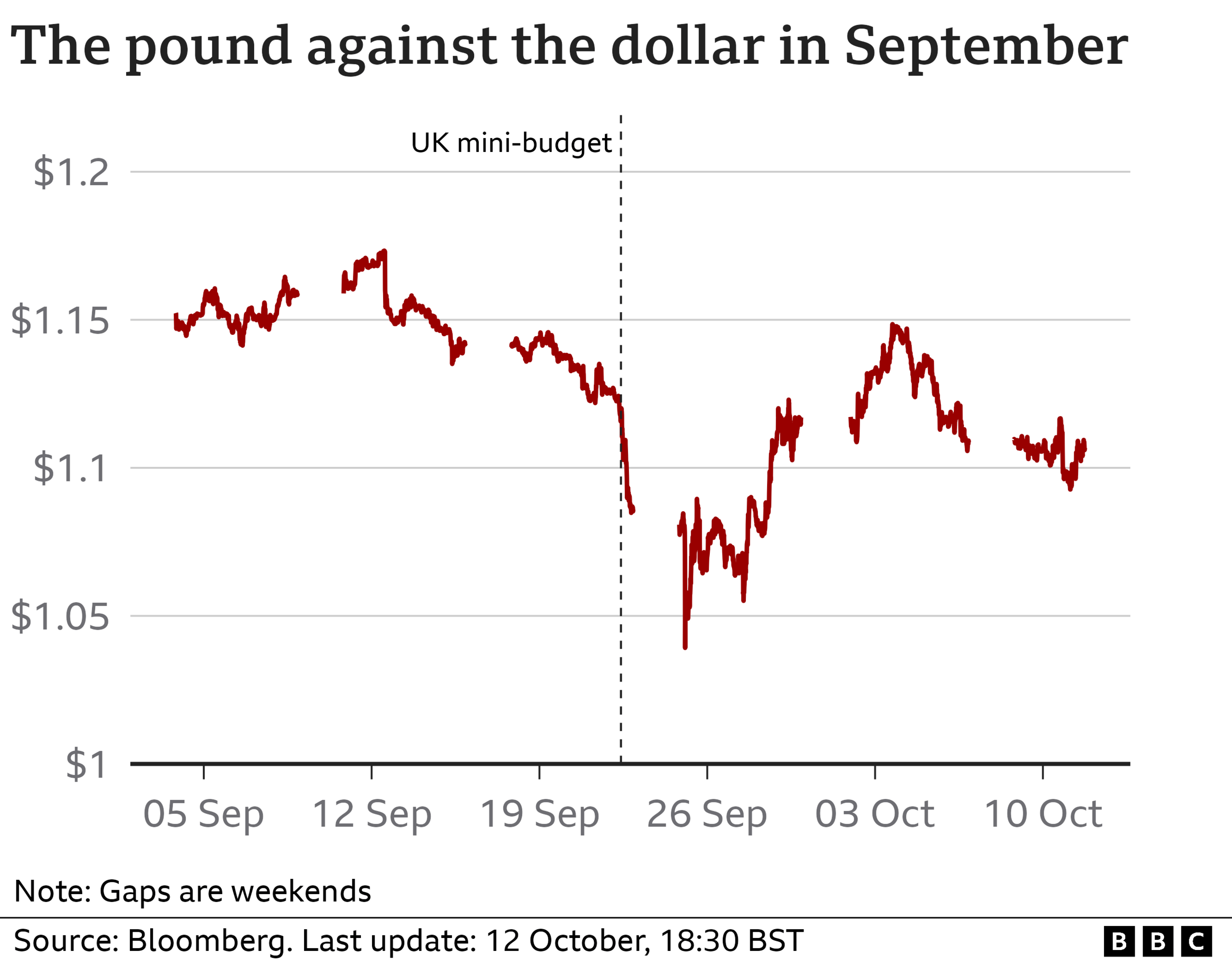

On Monday 26 September, the pound fell to record lows against the dollar in early trading in Asia. There was also a sharp rise in the cost of long-term government borrowing. Long-term gilt yields had gone up 0.5 percentage points by the end of the day, according to the BoE.

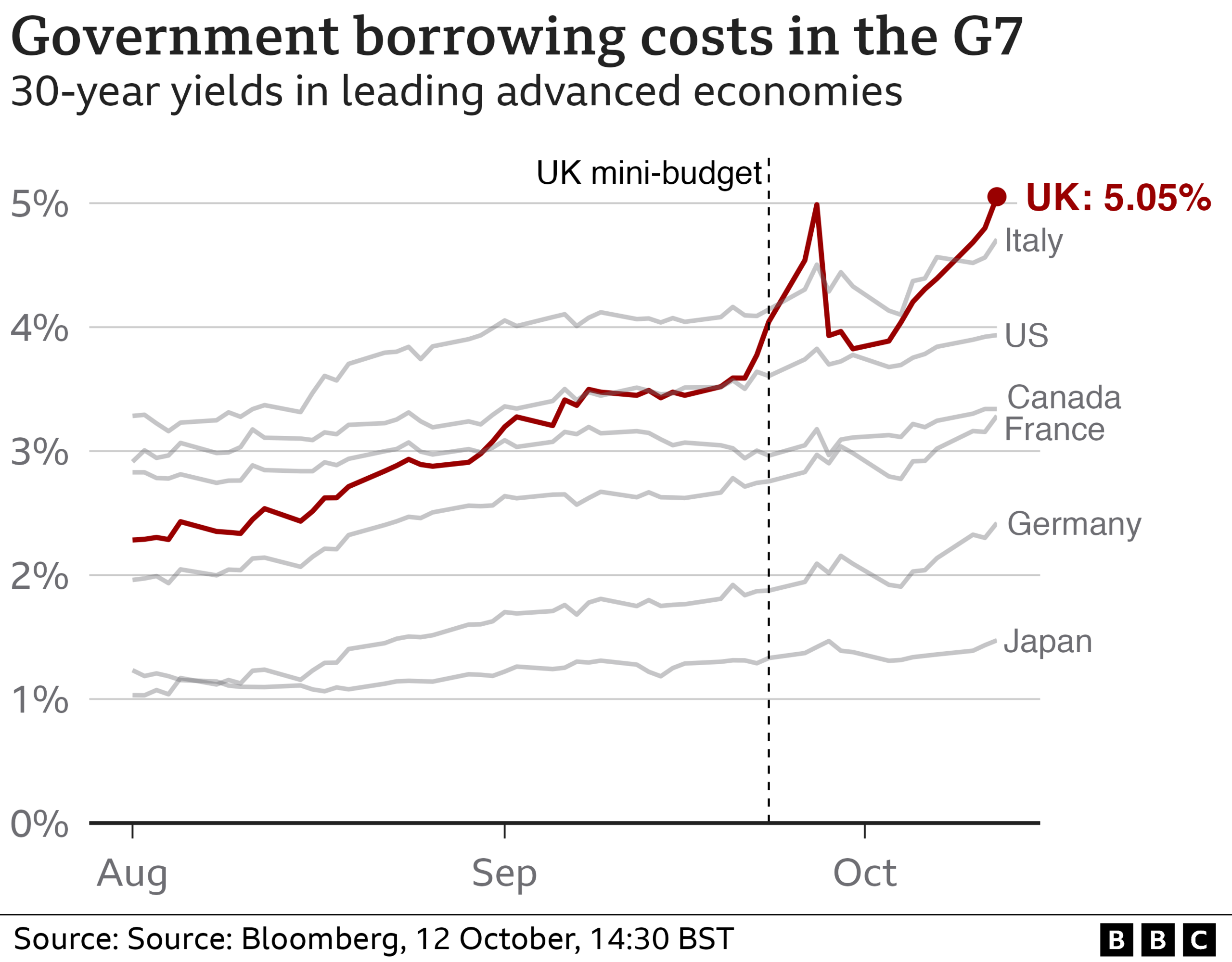

Comparing the cost of government borrowing - on this measure - across the G7 group of advanced economies, it is clear that there was a sharp spike in UK long-term borrowing costs following the mini-budget - which wasn't seen in the other countries.

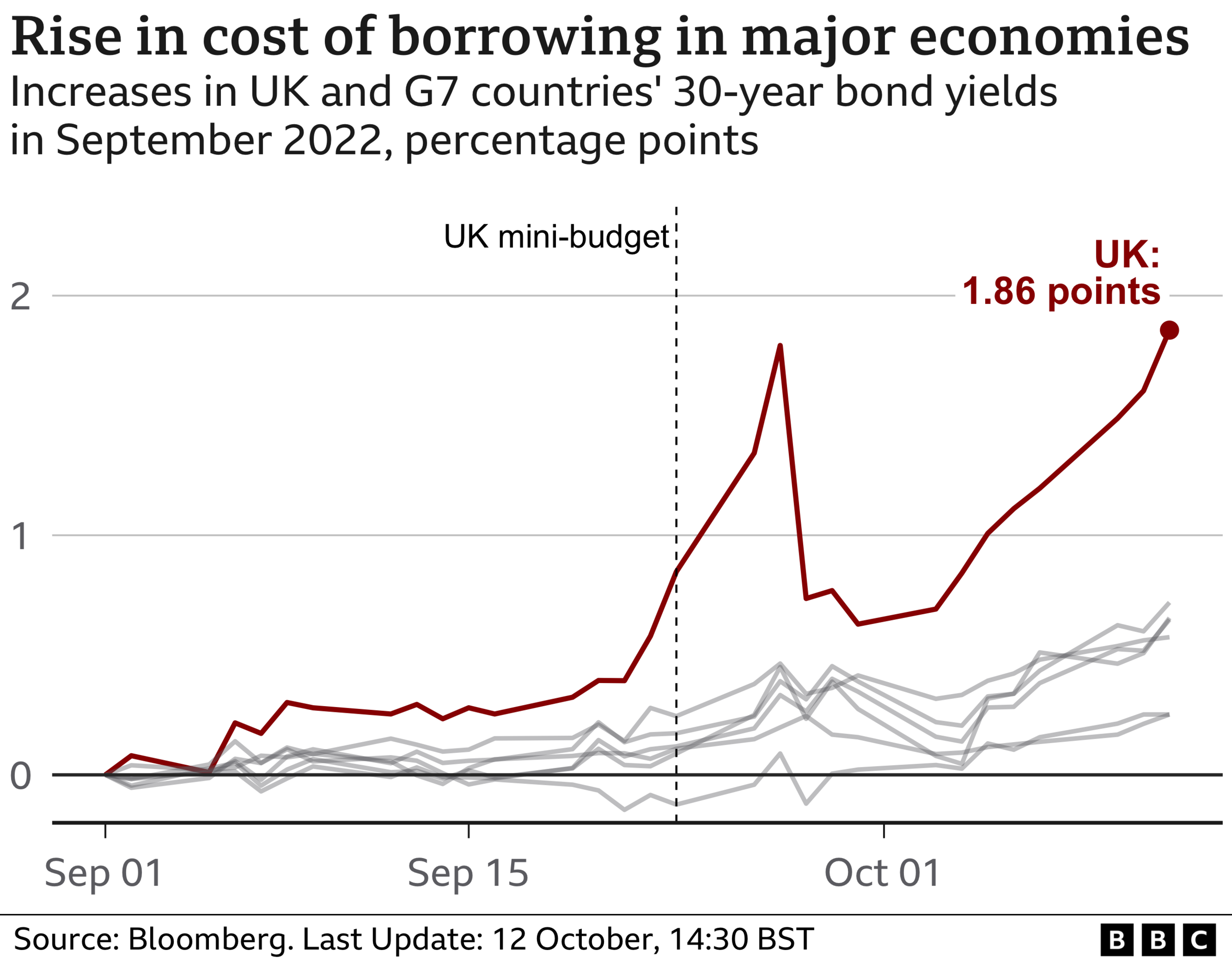

If you just look at the changes to the cost of government borrowing since 1 September (Liz Truss officially became prime minister on 6 September) the trend is even clearer.

The cost of borrowing for the UK government has risen considerably more in that period than it has in other G7 countries.

This increase fed through into rising mortgage rates with hundreds of products withdrawn from the mortgage market.

It also had an impact on UK pension funds - which trade in government debt (30-year gilts).

The BoE described, external the speed and scale of movements in interest rates on UK government bonds as "unprecedented". It had to step in to safeguard the pensions sector with a support scheme - worth a potential £65bn.

What was Liz Truss's involvement?

The change to corporation tax was a key pledge Liz Truss made during her Conservative leadership campaign.

On 11 August, she said she wanted to scrap the planned rise because, "I don't think that's a good way to get our economy going and to attract investment into our country."

The National Insurance cut was another of her campaign promises that made it into the mini-budget.

On the scrapping of the top rate of income tax, Ms Truss was asked who had come up with this - she said it was the chancellor's decision. Mr Kwarteng was asked whether he had got her backing for it before the announcement and replied, "of course".

On the absence of the OBR from the mini-budget, Ms Truss said the government didn't have time to wait for its forecast. The OBR wrote in a letter , externalthat it would have been in a position to produce an updated forecast for the 23 September announcement.

On the morning of 14 October, a Number 10 source told the BBC that the prime minister and chancellor were "in lockstep" - hours before she sacked him.

What are the experts saying?

Speaking on 29 September, BoE Chief Economist Huw Pill said the turmoil on the markets in part "reflects broader global developments... but there is undoubtedly a UK-specific component".

On 12 October, Sanjay Raya, chief economist at Deutsche Bank, told a committee of MPs that Russia's invasion of Ukraine as well as high inflation were causing global instability and volatility in the markets.

But he added that there was "absolutely a UK component here". Mr Raya said: "You throw on the 23 September event, you've got a sidelined fiscal watchdog, lack of a medium-term fiscal plan, one of the largest unfunded tax cuts that we've seen... since the early 1970s and it's sort of the straw that broke the camel's back."

Institute for Government chief economist Gemma Tetlow told the same committee that part of the problem had stemmed from the government undermining key economic institutions, "questioning their credibility and not asking for a forecast from the OBR".

She added that while the temporary emergency measures to limit energy prices probably could have been announced without an OBR forecast, "permanent changes to the tax system, which didn't need to be announced so quickly", could have waited for OBR assessments and "a full briefing from Treasury officials".

Gerard Lyons, an economist who advised Ms Truss and Mr Kwarteng during the leadership contest, speaking on the BBC's World at One programme admitted that the mini-budget "misread" the country's financial situation.

However, he argued that everything that has happened was not "solely due to the mini-budget" but also down to parts of the financial system that were vulnerable to interest rates going up.

What has happened since?

On 3 October, Mr Kwarteng U-turned on plans to scrap the top rate of income tax.

On 14 October, Ms Truss sacked Mr Kwarteng and announced a U-turn on corporation tax, confirming it will rise after all.

On 17 October, Chancellor Jeremy Hunt announced that "almost all" the tax measures of the mini-budget will be reversed - apart from the National Insurance cut and the changes to stamp duty. The energy bills support scheme will last for six months, rather than two years.