Blood scandal victim demands formal apology

Guernsey man Ian Walden believes those in power knew of the risks associated but failed in their duty of care

- Published

A Guernsey man who contracted hepatitis C from infected blood is calling on the UK prime minister to issue a formal apology over the scandal that destroyed thousands of lives.

Ian Walden, 61, wants the UK government to admit liability for failing to protect patients prescribed high-risk blood products imported from the US in the 1970s and 1980s.

He is one of the victims who submitted written testimony to the infected blood inquiry, external, which is set to conclude next month.

As a child Mr Walden spent countless hours receiving plasma transfusions to manage the inherited bleeding disorder haemophilia, which affects the body’s ability to clot.

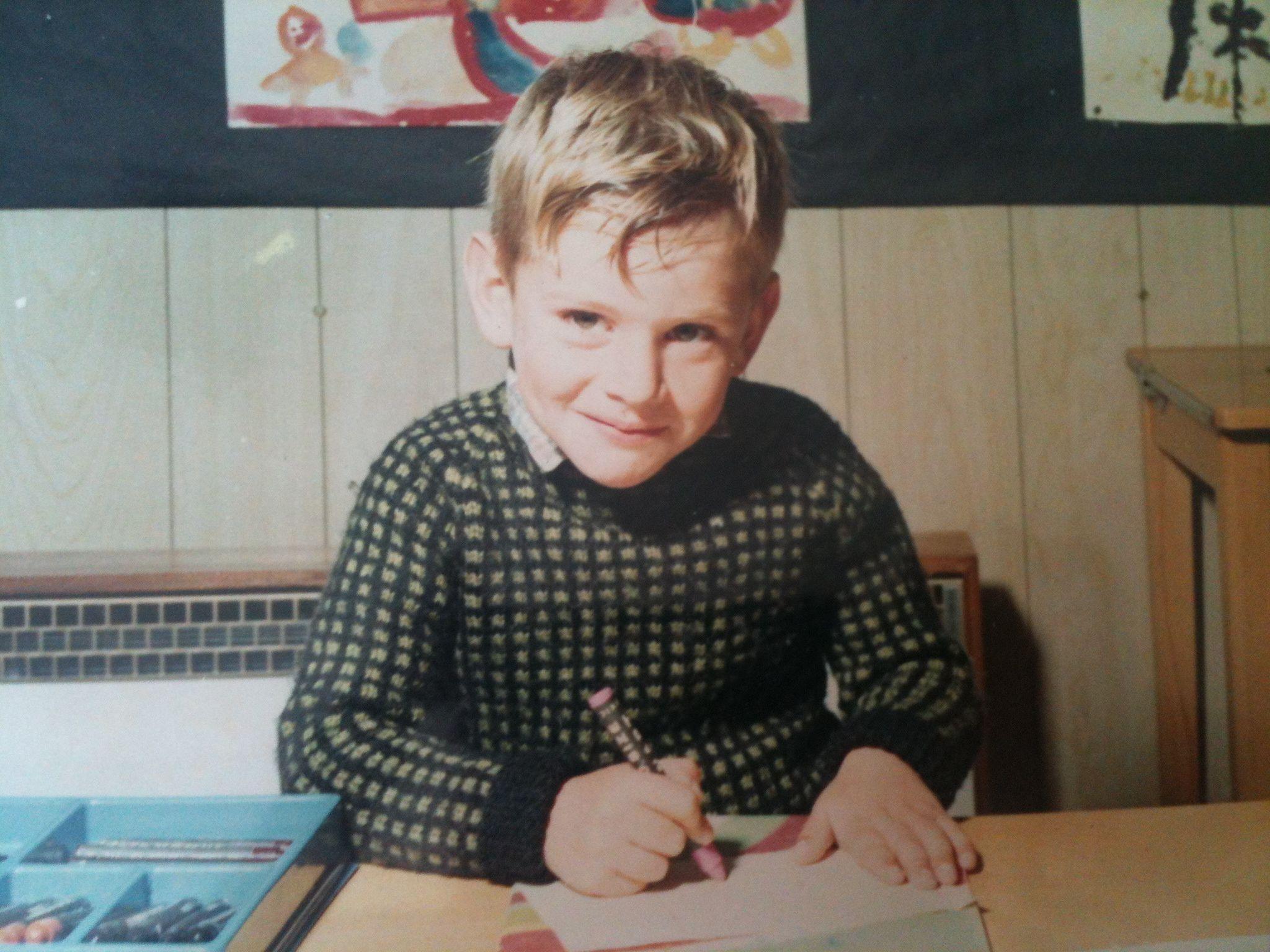

Ian Walden missed a lot of his schooling because of his blood disorder

"You’d go to school, get hurt and end up at the hospital that night with damage to the joints," he said.

"My youngest memory was having treatment in the children's ward over here – having frozen plasma dripping away.

"I missed a lot of schooling."

By the late 1970s he was prescribed a blood-clotting product, known as Factor VIII, that was seen to be highly effective for stopping bleeds but also widely known to be contaminated with viruses.

The treatment, which was a quick injection compared to lengthy transfusions, allowed him to lead a relatively normal life.

Mr Walden said: "I was older and here in Guernsey. I was doing a lot of gardening at the time and it was brilliant – it was a wonder product.

"You’d have an injection of that and know the bleeding would stop straight away."

What is the infected blood scandal?

The infected blood scandal involved some patients being given imported blood products, tainted with the HIV virus and other blood-borne viruses such as hepatitis B and C.

In many cases people died from complications from these blood-borne viruses.

It followed a high demand for blood-clotting treatments in the 1970s, with blood bought in from the US.

Some of this was donated from high-risk donors such as prison inmates and drug-users.

Victims say manufacturers, governments and medics knew of the risks associated but failed in their duty of care.

After years of campaigning, the UK-wide infected blood inquiry was announced in 2017.

Led by former judge Sir Brian Langstaff it took evidence between 2019 and 2023.

The inquiry is expected to publish its final report on 20 May.

Mr Walden said he was never warned of the risks of contracting viruses, such as HIV and hepatitis C and B, from the new treatment brought into the island from the UK.

Made from the blood plasma of thousands of US donors including prisoners and drug addicts, even one infected individual could contaminate a whole batch of the lifesaving concentrate.

In 1994 Mr Walden discovered he was one of 30,000 British residents the inquiry estimated were infected with a deadly virus.

It was only when he read a news article on the BBC television text service Ceefax about haemophiliacs with hepatitis C suing the government, that he requested a test.

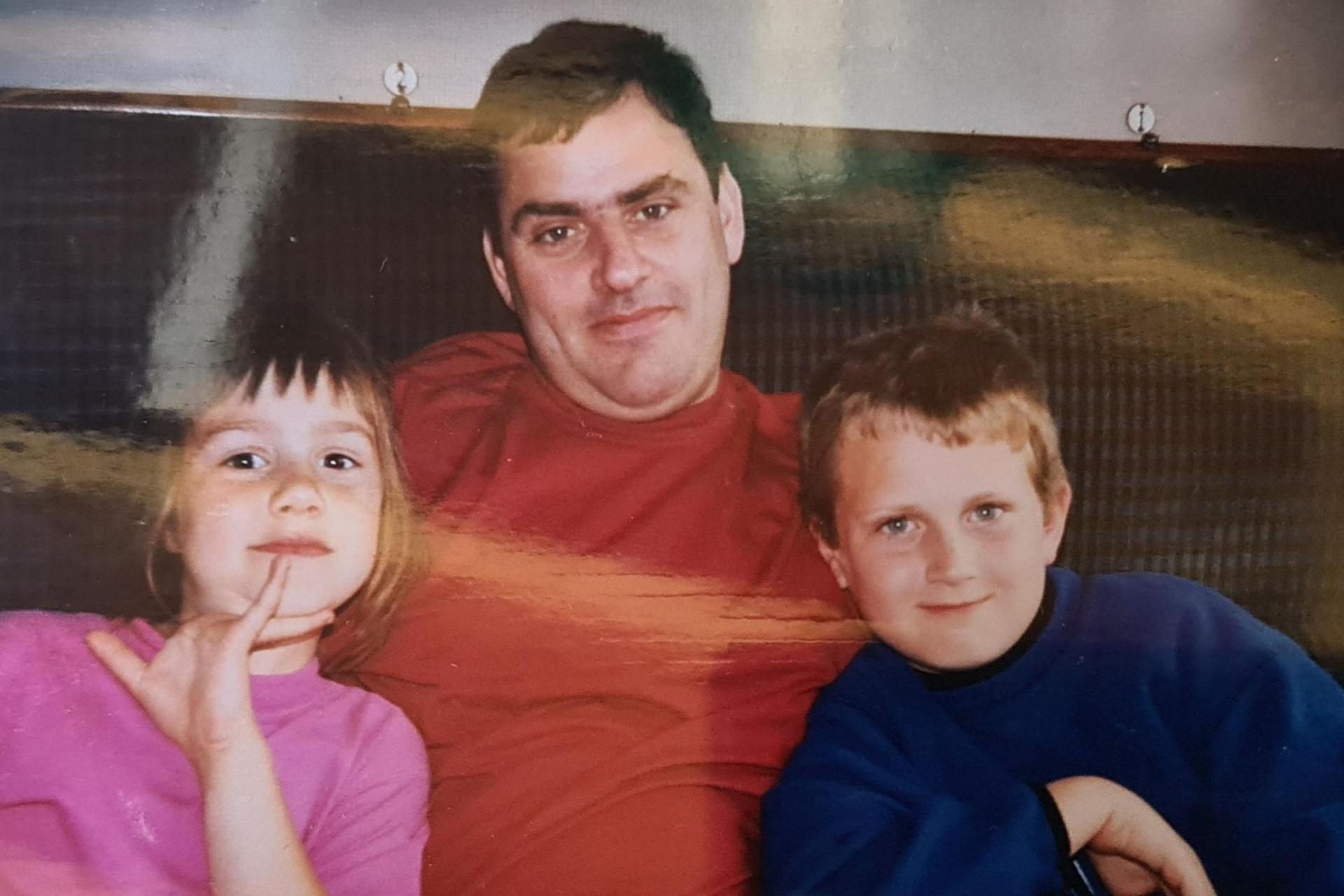

Ian Walden was concerned about the risks to his wife and his two children

He said: "I was told I had something that was killing people. I had a young family and everything going for me.

"My mood changed and I lost my get up and go.

"I was absolutely fuming no one had told me, my doctor, or the UK haemophilia clinic looking after me - it should have been known."

Mr Walden was sent to the UK for 18 months of gruelling hepatitis drug treatment, which caused him to suffer from hair loss and burning joints.

He said recent tests also showed he was carrying undiagnosed hepatitis B at the time. Both can cause chronic liver damage and cancer, and require regular screening.

He considers himself as one of the “lucky ones” who reacted well to treatment, while nationally it is believed about 10,000 people infected with the viruses have since died.

Read more on the infected blood inquiry

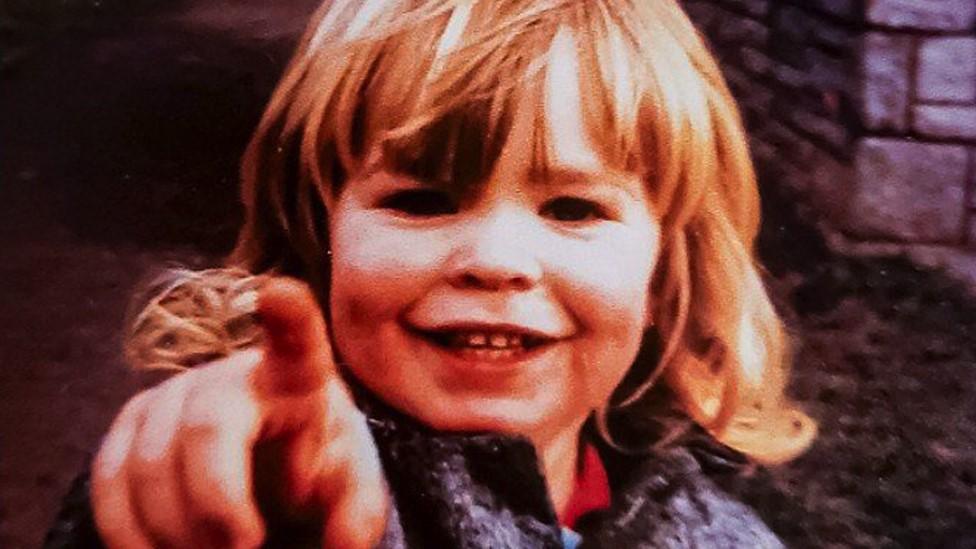

Ian Walden lived for many years without knowing he was carrying the deadly virus

Mr Walden is calling on someone to admit accountability over the treatment disaster, said to be the worst in the NHS’s history.

He said: “I’d like the government to be honest.

“They’ve sort of admitted responsibility for it but not stood up and said, ‘yes we’re guilty, we were wrong and we are going to put it right’."

In Guernsey it had been estimated there were between five and ten islanders affected by contaminated blood sourced from the UK.

Deputy Al Brouard, President of the Committee for Health & Social Care said the States had not worked formally with the UK inquiry but has been supporting victims.

He said: “Currently, the focus of the committee is working to ensure that affected people receive the support that they need and any compensation that might be awarded to them by the UK government in due course.

“A number of people infected with bloodborne viruses (mainly hepatitis C) through contaminated blood or blood products have been referred to the Orchard Centre for treatment.

“They have been supported through their treatment programme by the Orchard Centre who have also helped with the completion of information required for previous claims, for example from the Skipton Fund.”

Contaminated blood and haemophilia

From the 1960s to mid-1980s Factor VIII and XII, essential blood-clotting proteins haemophiliacs lack, were derived from the plasma of donors.

Without such treatment even the smallest injury could cause a haemophilic to bleed uncontrollably and prove fatal.

With later products came the risk of blood-borne viruses which manufacturers tried to combat with methods such as pasteurisation. But the risks remained.

If a single donor was infected with a blood-borne virus such as hepatitis or HIV then the whole batch of medication could be contaminated.

By April 1985, all Factor VIII and XI products used in the UK were heat-treated to prevent contamination in the wake of the HIV outbreak.

Then by the late 1990s the use of synthetic clotting factors were used to treat the disorder, eliminating the risk of future contamination.

A UK Government spokesperson said: "This was an appalling tragedy, and our thoughts remain with all those impacted.

“We have consistently accepted the moral case for compensation, and that’s why we have tabled an amendment to the Victims and Prisoners Bill which enables the creation of a UK-wide Infected Blood Compensation Scheme and establishes a new arms-length body to deliver it.

“We will continue to listen carefully to those infected and affected about how we address this dreadful scandal.”

Follow BBC Guernsey on X (formerly Twitter), external and Facebook, external. Send your story ideas to channel.islands@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

Related internet links

- Published18 April 2024

- Published14 April 2024

- Published22 June 2023