Mum never got over injecting son with infected blood

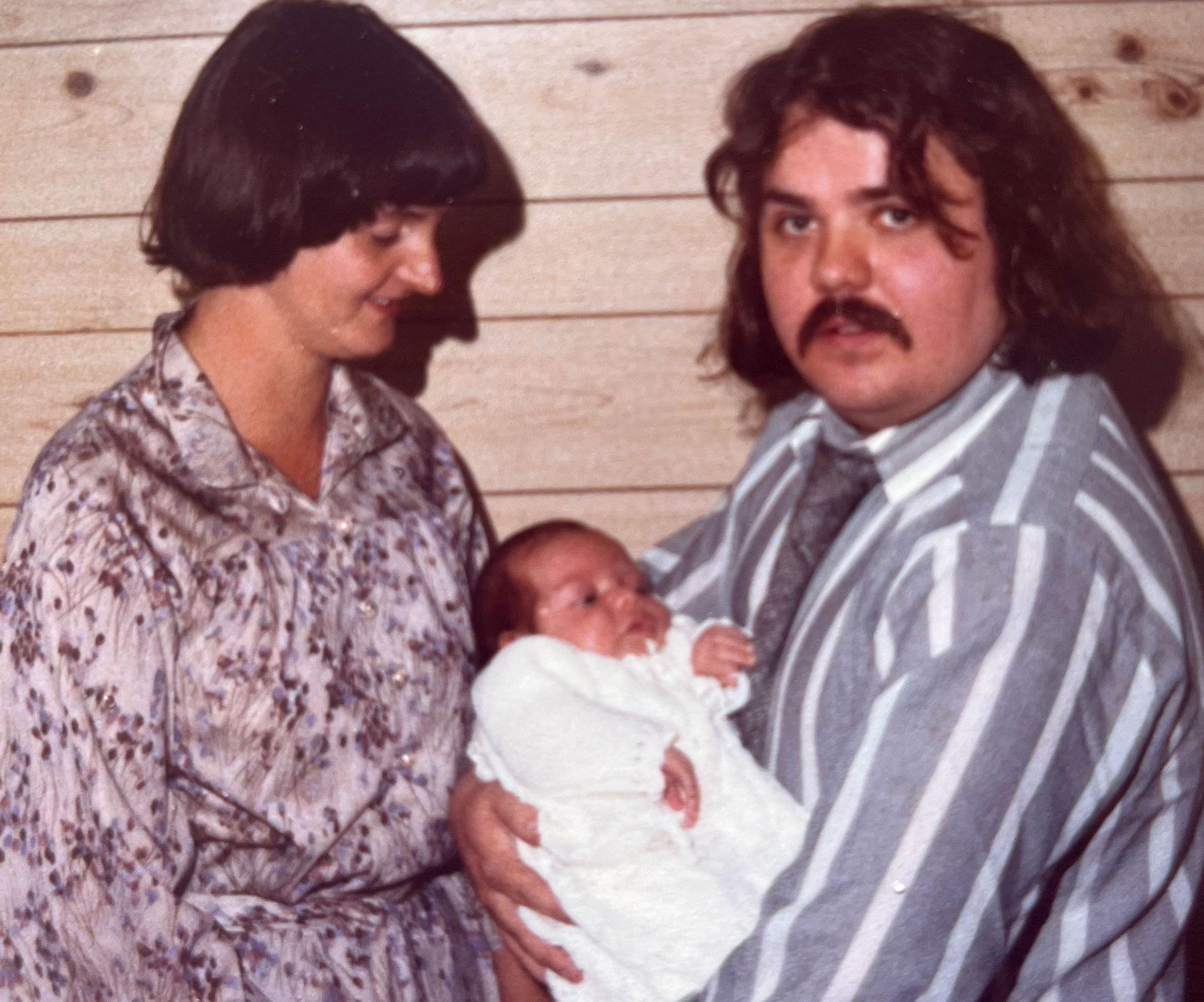

Kate McDougall with her son Euan, who died aged 16

- Published

Euan McDougall was just 16 when he died from Aids in 1994 after being infected with HIV by blood products used to treat haemophilia.

Under the care of doctors at Yorkhill Children’s hospital, he became one of the thousands of victims of what has been called the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS.

His mum Kate died earlier this year, exactly 30 years after her son.

According to her ex-husband John, she is another victim of the scandal as she never got over her unwitting role in causing Euan’s illness.

"The exceptional pressure ate away at her for decades, which saw a long, slow deterioration in her health," John says.

"She never got over what happened to Euan."

Later this month, five years after it began taking evidence, a public inquiry into the infected blood scandal will publish its findings.

John says he needs to make sure both Euan and Kate are remembered after it ends.

'Injecting son with infected blood played on mother's mind'

Euan was born with haemophilia, a hereditary condition – of which Kate was a carrier – which put him at risk of life-threatening bleeds and restricted his life.

But in the late 1970s a new treatment regime was introduced which involved preventative injections of the blood-clotting agent Factor VIII.

Euan was one of a group of more than 20 boys treated at Glasgow's children's hospital in Yorkhill, under the care of lead clinician Dr Michael Willoughby, then seen as a pioneer in his field.

The difference it made to Euan's life was phenomenal, his dad says.

"He learned to cycle – the little stabiliser wheels soon disappeared and he was cycling all over the place, playing in the garden, climbing trees," he says.

But then it all went tragically wrong.

Euan was born with haemophilia, an hereditary condition – of which Kate was a carrier

Some of the blood used to make Factor VIII was sourced from UK donors but often it was imported from the United States where donors were paid.

Throughout the early 1980s there was growing evidence that some of the blood products were contaminated with HIV or Hepatitis C.

Euan was not quite eight years old when he tested positive for HIV in 1985.

Four years later, John and Kate were called to the hospital to be told the virus had “activated” into full-blown Aids.

By September 1990, John says there had been a rapid change in Euan.

“He shrunk in every direction, he just got smaller and smaller, thinner and thinner, skin and bones," he says.

"From being second tallest in his class he became the smallest. He used to be outgoing and he became more shy. It was physically obvious.”

At first the treatment made a phenomenal difference to Euan's life

Now 75, John still has the notebook where his wife logged all the hundreds of Factor VIII injections she gave Euan and the notes alongside them.

At least one of them – and probably many more – were the source of Euan’s HIV infection. He says this always played on her mind.

“It was an endless strain on Kate," he says.

“I remember after Euan died Kate said, ‘I wish it was you’. And then she said, ‘I wish it was me. I wish it was anyone’."

Euan's dad John says there were not told of the risks of the blood products

John says doctors at Yorkhill never explained the risks of the blood products.

He says he found out in other ways.

He recalls a newspaper article stating that each batch of Factor VIII included blood from thousands of donors – making it so high risk that statistically all haemophiliacs were likely to become infected with HIV, and eventually die of Aids.

It left him with a sense of dread.

“As parents we knew a bit about it," he says.

"The doctors knew a thousand times more than that.

"Haematology doctors were professionals in that field. We were very concerned. But the doctors were saying it was all ok – it’s not a problem.”

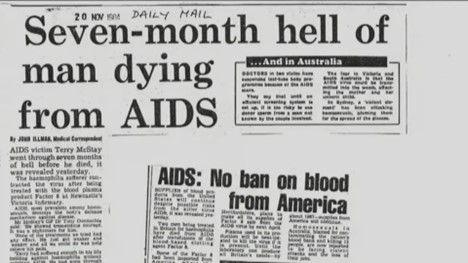

Kate's brother Terry (right) was also a haemophiliac and was being treated in Newcastle

While they were being reassured by the doctors at Yorkhill, the McDougalls were hearing first-hand warnings from Terry McStay, Kate’s brother, who was also a haemophiliac and was being treated in Newcastle, where he lived.

From the end of 1983 he had fallen ill, and was contacting the family every couple of months to tell them not to allow Euan to receive the American Factor VIII concentrate he'd been treated with.

In 1984, Kate's family went down to Newcastle to bring Terry home to Wishaw. A bed was made up for him downstairs in the living room beside the television, so the family could all sit together.

Terry was the first haemophiliac to die of AIDS in Scotland, in November 1984, and it was front page news.

A year earlier the government had insisted there was no "conclusive proof" that HIV could be transmitted in blood but by the end of 1985, all Factor VIII products were heat-treated to kill the HIV virus.

By the time of Terry's death, Euan had been receiving Factor VIII for almost five years.

It was not until five weeks after her brother's death that Kate's log of treatments shows that Euan received "heat-treated" products for the first time.

Terry had always insisted that this process was the only way to kill off any viruses in donated blood.

But it was too late.

Six months later, at a regular appointment in April 1985, Kate was informed that Euan was HIV positive.

At that clinic, at least two other parents were given the same news.

John and Kate had a longer meeting together with a doctor a few days later.

"It felt like a one way ticket," John says.

"His death was inevitable but the doctor didn't express any regret at the time."

John says the mental pressure on Kate was immense.

"She was grieving for Terry but also knew the path we were going down with Euan," he says.

John says Euan didn’t know his diagnosis

However, John says the couple went to great lengths to make sure Euan didn’t know his diagnosis.

"We’d be sitting watching television and the famous AIDS tombstone advert would come on, and we’d sit watching it and we’d talk about football or something," he says.

“In the early years he had no symptoms and we didn’t want to worry him, but there was also the stigma, which was horrendous. It’s hard to believe now.

“It’s the most amazing strange thing, 40 years later, looking back on it. I can count on one hand the number of people we told," John says.

Euan was one of a group of more than 20 boys treated at Glasgow's children's hospital in Yorkhill

Years later, John saw an anonymous list of 21 boys who had been infected with HIV while being treated at Yorkhill. He believes at least half of them died as a result.

Although the McDougalls never openly discussed Euan’s diagnosis, John believes he must have worked it out through conversations with the other Yorkhill boys.

“Euan would be talking to 14, 15 year olds, and they’d been through all the same things he’d been through, so they were really close," he says.

“As time went on some of these boys would die.

"They didn’t go to each other’s funerals but Euan was a smart guy, he could work out what was going on.

"We never sat down and had a conversation about it. I don’t know whether I regret that or not."

Euan was increasingly unable to go to school

By 1993, Euan was increasingly unable to go to school. Now with full-blown Aids, Euan had episodes of paralysis where he couldn’t move for three or four hours at a time.

He would communicate with the family by blinking and they’d put the football on the radio.

“He used to say 'we’ve been dealt the cards we’ve been dealt', and we just had to just make the best of it,” John says.

Euan named his boat Butterfly 23, after the needles used for his many intravenous drips

Euan got a settlement payment of £20,000 in 1993, which he wanted to spend on a motorhome.

But at the dealership there was a boat that caught his eye, and he said, "I want that boat".

So they bought a 29ft boat and the next day it was in the water at the marina at Cameron House on Loch Lomond.

John says it gave Euan a huge amount of joy. He named it Butterfly 23, after the needles used for his many intravenous drips.

“The first time we came down, I drove the boat out to the bottom of the loch and then Euan pushed me out of the way and he said, ‘Let's see what this baby can do’,” he says.

Euan took over the wheel and the boat planed up out of the water, and for 26 miles it flew up to the top of Loch Lomond and back down again, overtaking the traffic on the A82 on the shore.

“He loved it, absolutely loved it," John says.

"The last time they were on the boat was on his last birthday in June 1993 when he was 16.

"All his pals were there on the boat, and it was a fantastic party. But after that he was too ill to go back.”

Euan died seven months later, on 12 January 1994.

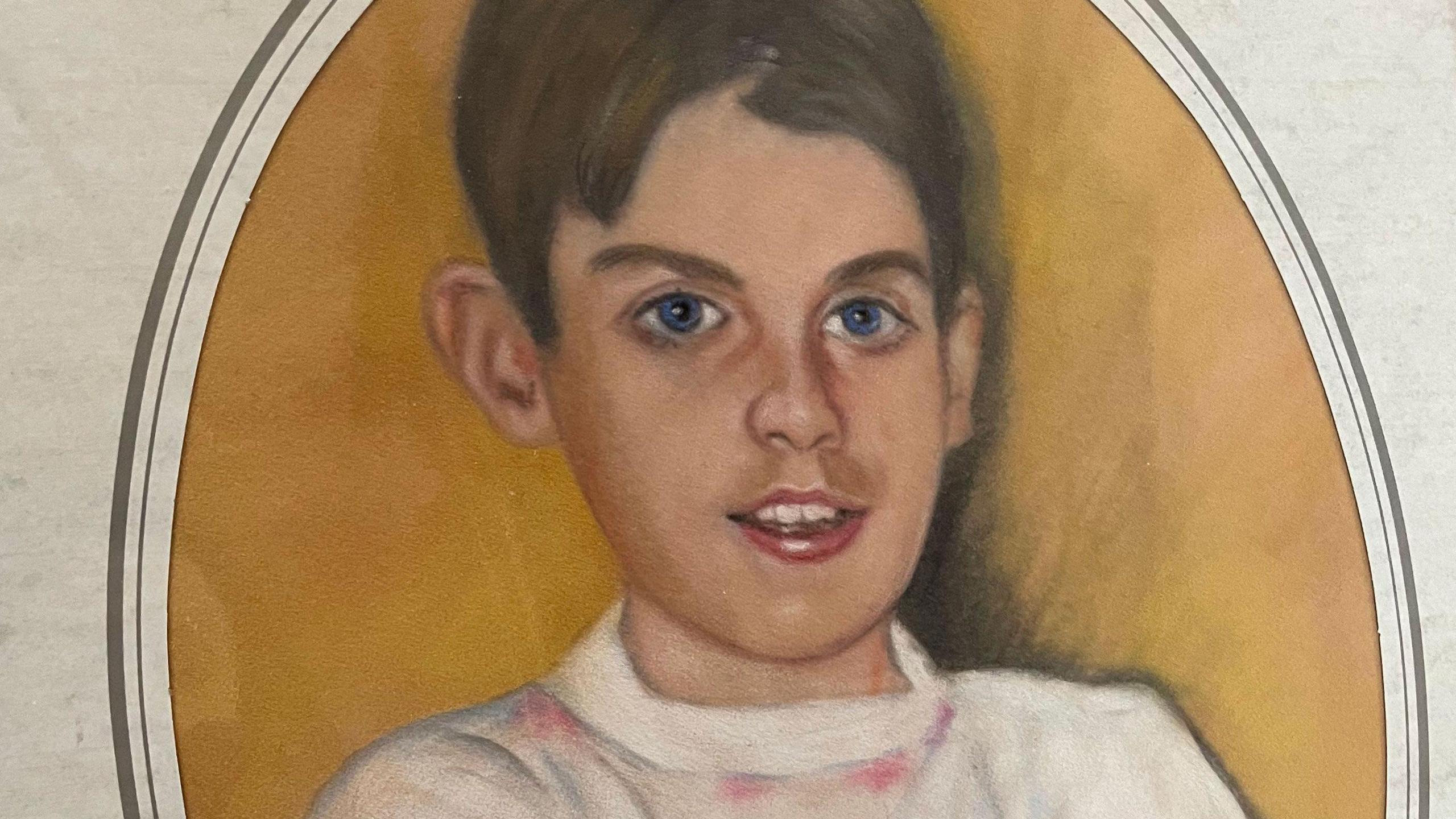

A portrait commissioned by Euan’s grandparents after he died

Dr Willoughby, the lead clinician at Yorkhill, emigrated to Australia in 1982, in the midst of a staff work-to-rule at the children's hospital.

When approached by the inquiry team in 2019, the 92-year-old struggled to answer a series of written questions, but expressed his condolences to John McDougall. He died the following year.

John does not expect the inquiry’s final report to answer his questions, such as why the staff at Yorkhill were still using American Factor VIII when other hospitals stopped in 1983, or why blood products were not heat-treated earlier.

“They should have sat down and discussed the risks with us, instead of denying the evidence," he says.

“In terms of people holding their hands up and saying this was wrong, specifically about Yorkhill, it’s not job done.

"I don’t think the job will ever be done because it’s 40 years ago. It's not going to happen.”

John McDougall, now 75, says he does not expect the inquiry’s final report to answer his questions

Kate attended the inquiry alongside John when he gave evidence in 2019. She described the huge void in their lives after Euan died.

The couple eventually separated and finally divorced in 2018.

Kate died in January and John believes she never recovered from losing her son.

"Her short term memory suffered and she spent two years in a care home before she died.

“To me Kate is the latest victim," he says.

"She died three months ago as a direct consequence of what went on.

"I want people to know about Euan, and Terry, and Kate. That’s what it’s all about. If I don’t tell their stories, nobody will.”