The Army is shrinking - but would Labour make it any bigger?

- Published

Sir Keir Starmer has been outlining how the UK would be "fit to fight" under a Labour government and attacking the Conservatives’ record on the armed forces.

One of his claims is that the Tories have cut the Army to its smallest size "since Napoleon" and missed recruitment targets every year.

Is this accurate? And is it fair to compare the needs of a modern army to those of early 1800s warfare?

Smallest army since Napoleon?

On the narrow statistical point about the Army's size, the Labour claim does seem to be broadly correct.

And it has been the government’s explicit policy to reduce numbers.

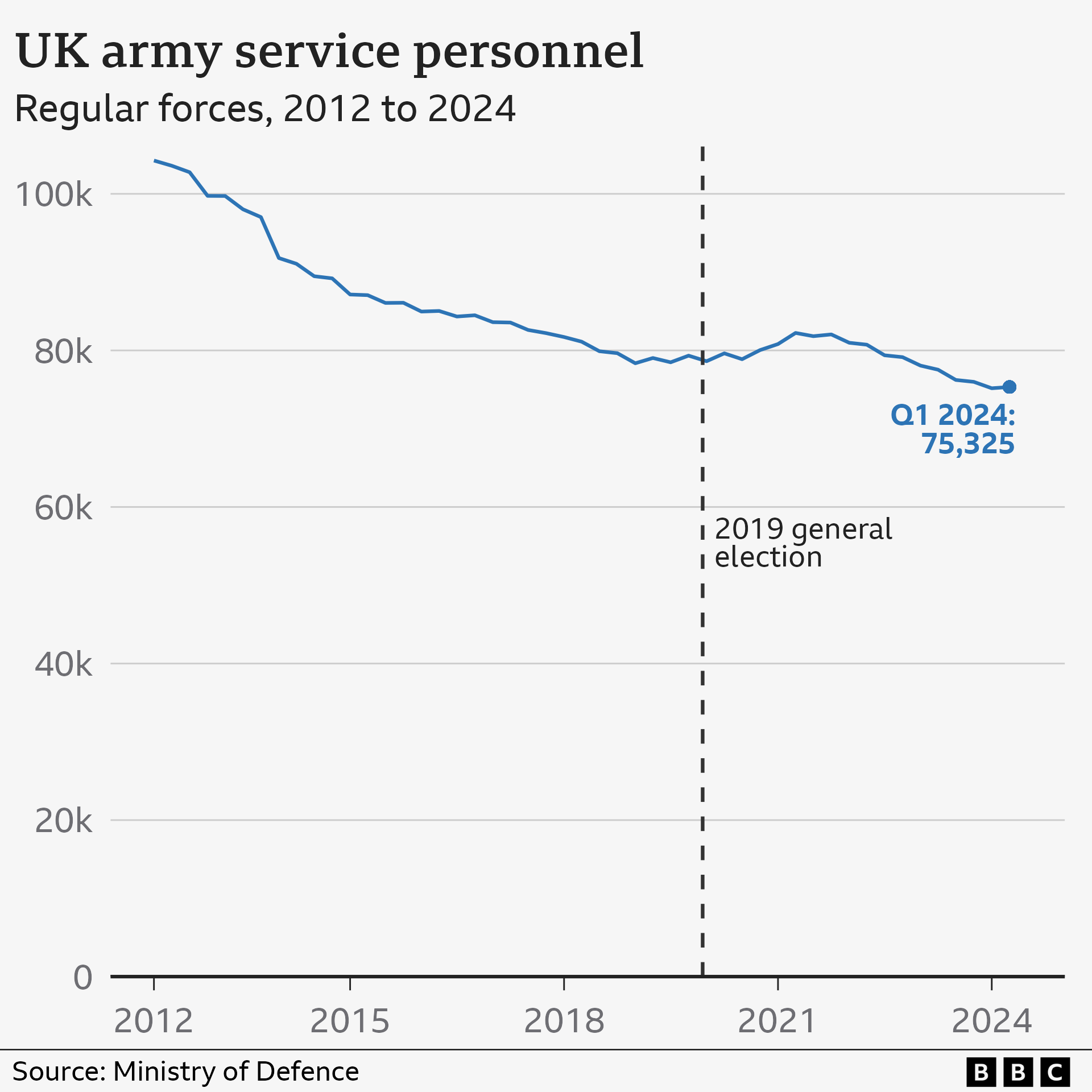

As of April 2024, there were 75,325 members of the UK’s regular Army forces (excluding Gurkhas and volunteers), according to the latest Ministry of Defence (MoD) figures, external.

That’s down from 79,330 in October 2019, just before the last election.

In 1800 - at the start of the Napoleonic era - the Army was about 80,000-strong, according to data released by the MoD in 2017, external.

It's worth keeping in mind that today’s Army has a reserve force of more than 30,000.

If we put that together with the regular force, we get to a total larger than in the days of Napoleon.

However, it doesn’t necessarily make sense to use the number of soldiers back then as an appropriate benchmark of defence capability.

After all, it was a radically different military era, with cavalry rather than tanks and cyber threats.

Is Labour's 2030 green energy goal realistic and how would it affect bills?

- Published31 May 2024

As for Labour's record, the size of the Army in 2010, when the last Labour government left office, was about 100,000, external - a figure that had been roughly stable since 2000.

Though under Labour, the total size of the armed forces personnel - including the Navy and air force - steadily declined.

A Conservative government review of the UK’s foreign and defence policies in 2021 recommended a shift in focus and use of resources, with a "tilt", external to the Indo-Pacific region in recognition of the military rise of China.

After this, the government reduced the target for Army numbers from 82,000 to 72,500 by 2025.

Missed recruitment targets

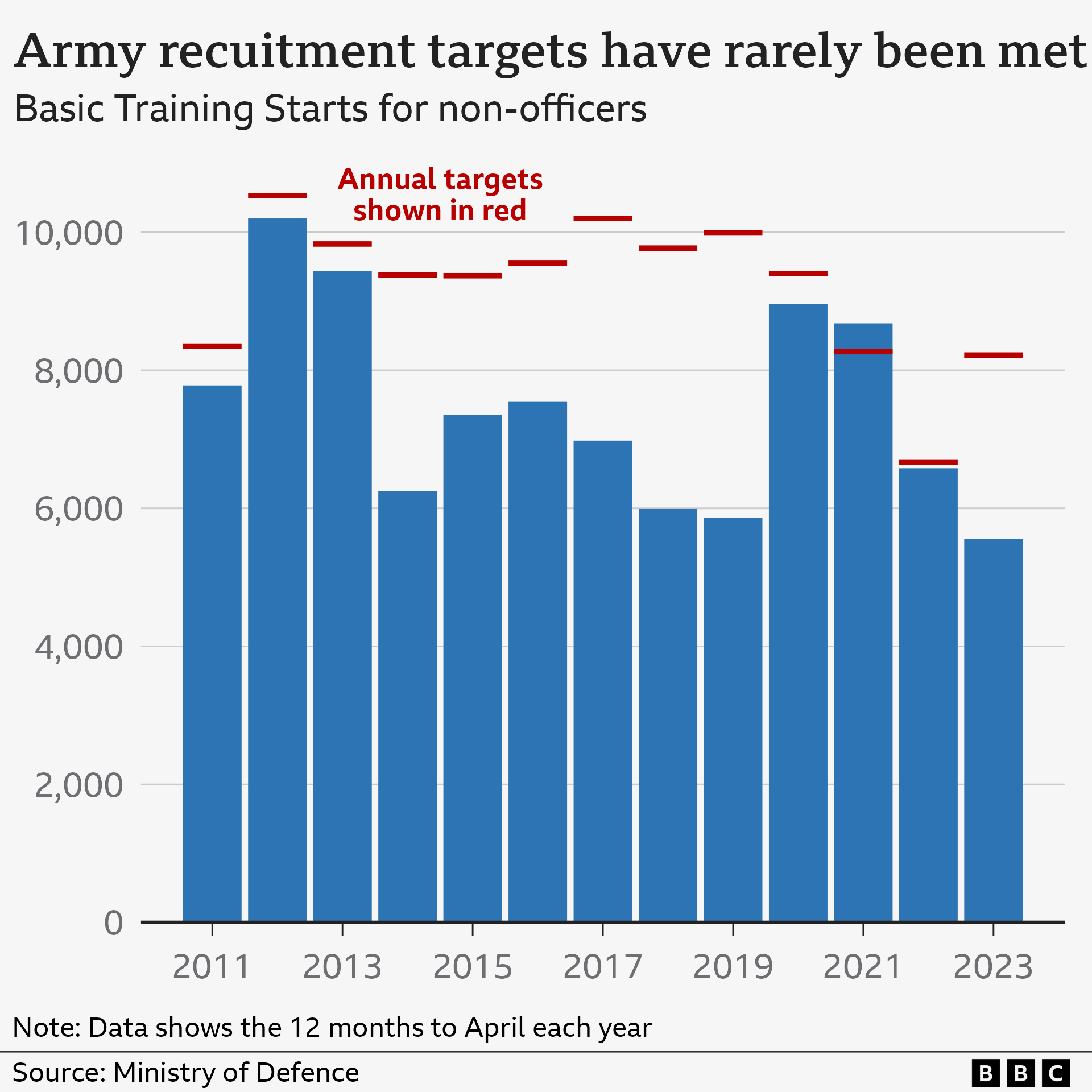

The Army has targets on how many new recruits below the rank of officer it should take on every year, set out by the Ministry of Defence.

These targets have been missed in almost every single financial year since 2010-11, according to a written answer, external to Parliament by Defence Minister Andrew Murrison last January.

The only exception was 2020-21, when the target was reduced following the government’s policy review.

The Army’s recruitment difficulties will probably make the government hit its 2025 army headcount reduction target of 72,500 earlier than planned.

But remember that cutting down has been the policy of ministers.

What would Labour do?

While Labour may be broadly right on the shrinking size of the Army, it is not clear what they would do if they won power.

They have not pledged to increase the number of soldiers. All they've said is that they would hold a strategic defence review after the election.

And it's not clear what this review would recommend in terms of numbers.

Moreover, Labour's commitment to keep the UK's Trident nuclear submarine deterrent would limit their financial ability to boost military personnel numbers.

Trident’s running costs are estimated, external to be about £3bn a year - and that sum does not include the capital costs of building four new submarines, which Sir Keir also says he will do.

That £3bn accounts for about 5% of the entire defence budget, which will be £55.6bn, external in 2024-25 - making up about 2% of GDP, the annual value of all the UK economy’s goods and services.

Labour says they would raise total defence spending to 2.5% of GDP "as soon as resources allow".

This is more vague than the Conservatives, who have pledged to hit this spending target by 2030 (though claims they could largely pay for this by cutting the number of civil servants back to pre-pandemic levels look questionable).

How does the UK compare with other economies?

- Published23 May 2024

With Labour saying they are the party of national defence, Conservatives have pointed out that shadow foreign secretary David Lammy and deputy leader Angela Rayner voted against renewing Trident in 2016 in a parliamentary vote.

This is correct, external, but Keir Starmer voted in favour of renewing it and Labour formally supported Trident in its 2019 election manifesto, external.

Perhaps the bigger challenge for Labour if they won power would be grappling with the same strategic and financial trade-offs as the current government, between maintaining the numbers of military personnel and investing in technology to counter new emerging security threats such as cyber attacks and artificial intelligence.

At the time of the 2021 review, then-Defence Secretary Ben Wallace justified a planned reduction in the size of the Army by saying, external: “When the threat changes, we change with it… It’s really important we’re driven by the threat not sentimentality.”

To govern is to choose, and a future Labour government - just like the Conservatives since 2010 - would be forced to choose its priorities when it comes to defence.

- Published7 June 2024

- Published4 June 2024