The 'radical' Manchester event that changed Africa

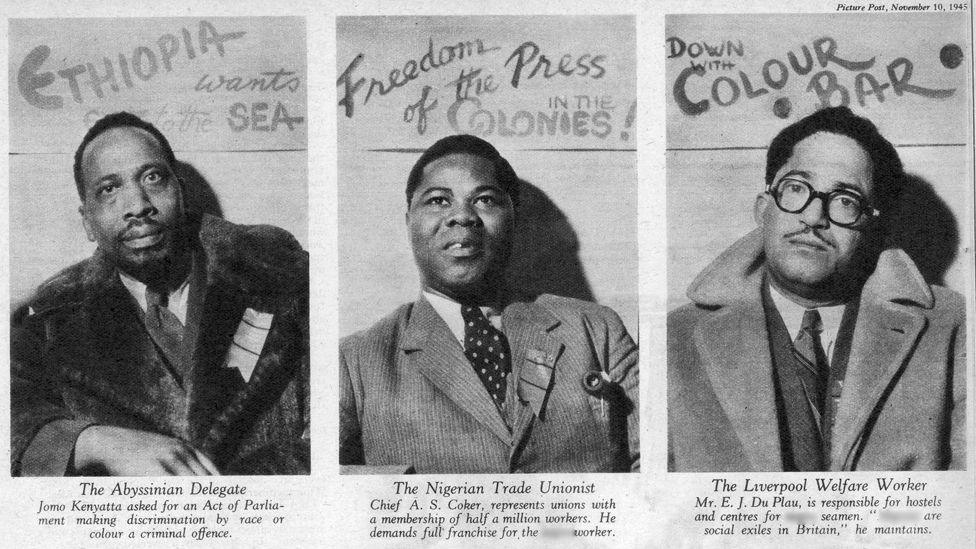

Jomo Kenyatta, who would become the first president of the Republic of Kenya in 1964, was one of many major names who attended the event

- Published

In October 1945, delegates from across the world descended on a town hall on the outskirts of Manchester city centre to attend a seismic event in African politics, the ripple effects of which still resonate 80 years later.

The Fifth Pan-African Congress, held between 15 and 21 October 1945, was a key moment for the movement that liberated many Africans from colonial rule.

Among those who attended were Obafemi Awolowo, one of the driving forces of Nigerian independence, feminist and human rights campaigner Amy Ashwood Garvey, Trinidadian radical George Padmore and the future presidents of Malawi, Ghana and Kenya - Hastings Banda, Kwame Nkrumah and Jomo Kenyatta.

But it was not, as its name makes clear, the first such gathering, so how did it come to have such significance and why was it held in Chorlton-on-Medlock Town Hall?

What is Pan-Africanism?

Pan-Africanism is a philosophy which held that all people of African descent should unite to stand against racial injustice, inequality and colonialism in Africa.

It began in the mid-19th Century but came to the fore in the early 20th Century, when Trinidadian barrister Henry Sylvester Williams organised the First Pan-African Conference in London in 1909.

That event was followed by Pan-African Congresses in 1919, 1921 and 1923, which were held either solely or jointly in Paris, London, Brussels and Lisbon, four cities which had been the seats of European colonial power, before a fourth event in New York in 1927.

Each congress ended with a list of resolutions, which were mainly made around the need for more rights for Africans, for the end of British rule and for home rule and a say in the governance of their own countries.

Why was Manchester chosen?

The Pan-African movement was disrupted by world events in the 1930s and 1940s and did not hold a congress again until after the end of World War Two.

Its leading figures were keen to get things going again after that conflict was finally ended with Victory over Japan Day on 15 August 1945.

Within two months, delegates were filing into the main chamber at Chorlton-upon-Medlock Town Hall to see the start of the Fifth Pan-African Congress.

Its aim was to tackle the post-war struggle against racial discrimination and help its delegates find a path to liberation for those living under what they saw as unjust colonial rule.

Harry Eyre, an expert on the congresses who helps with the documenting of black histories as the librarian for the Ahmed Iqbal Ullah RACE Centre and Education Trust, said there were a "plethora" of reasons why the city was chosen to host.

The main one, he said, was the strength of black communities and their established network of businesses in Manchester.

Ras T. Makonnen, for example, owned a number of restaurants, hotels and nightclubs, so people travelling from all over the world had places to stay and eat.

He acted as treasurer for the congress and is named on a plaque commemorating the congress on the building where it was held, which is now part of Manchester Metropolitan University.

Harry said Makonnen was friends with Padmore, who has been described as "one of the most influential black political thinkers of the 20th Century", and the pair were both instrumental in bringing the event to Manchester.

Harry's colleague Maya Sharma, the head of the trust, added that in their archives, there was evidence that there had been an "African and Caribbean presence in Manchester for decades", long before the arrival of the Windrush generation.

She said the Oxford Road area around the town hall had a flourishing black community with businesses such as cafes, restaurants and a bookshop.

Who was involved?

Many of the delegates at the congress were political heavyweights, activists and vocal supporters of the Pan-African movement.

They came from Manchester and the surrounding area, from other parts of Great Britain and more than 25 other countries, the majority of which were still part of the what had become known as the British Commonwealth of Nations.

They represented more than 50 organisations and political associations, from the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom to the Communist Party of Great Britain.

Among the speakers was Jamaican activist Amy Ashwood Garvey

Alongside Awolowo, Ashwood Garvey, Padmore, Banda, Nkrumah and Kenyatta were the likes of African National Congress activist and writer Peter Abrahams, Sierra Leone People's Party founder Lamina Sankoh, All African Convention founder Davidson Don Tengo Jabavu and Tikiri Banda Subasinghe, who would go on to serve as the Speaker of the Sri Lankan Parliament.

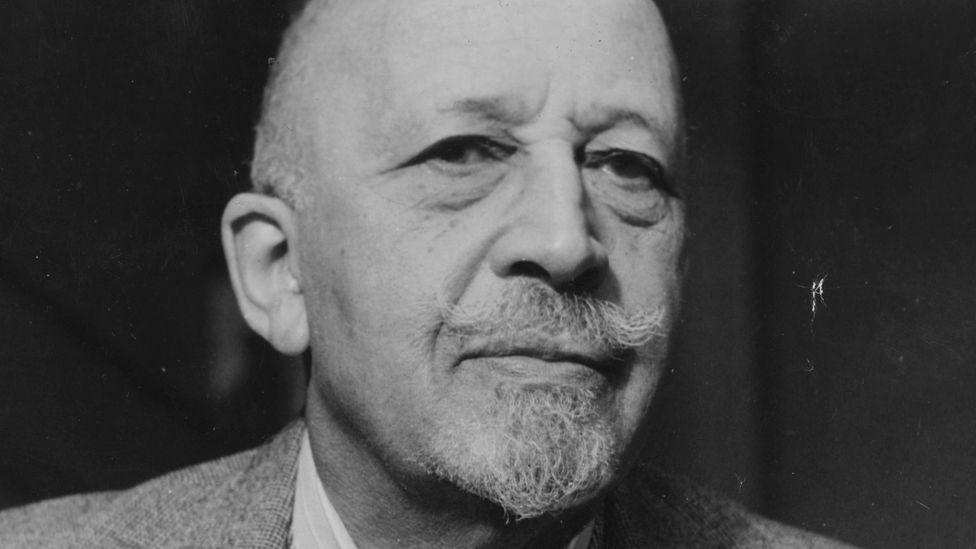

There was also at least one delegate who had been there from the start, as the congress chairman was William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, the African American thinker and journalist who had helped to organise the first event in 1919.

Why was it so significant?

Harry said the congress was unique as the previous ones had involved primarily people of upper classes and of professional backgrounds.

In Manchester though, the event catered for a much larger demographic of activists from all over the world as well as also from black communities in the UK and specifically the city itself.

He said while its impact was not "instantaneous", it "led to the success of independence movements" in decades that followed across the British Empire and other colonial strongholds.

More than 200 people attended the various lectures to hear the delegates speak and debate

He said Jomo Kenyatta and Kwame Nkrumah, who would go on to lead homelands of Kenya and Ghana independence, came together to plan the means with which they would eventually achieve that.

"It was a sort of zenith of the movement, the beginning of the struggle after the Second World War," he added.

Alongside the daytime political debate, there were also evening social events at the congress

Maya said the Manchester event "raised some very clear demands" which included an end to colonial rule in Africa and the Caribbean and racial equity for people of African heritage everywhere.

"They also demanded economic justice and fair wages," she said.

"I believe these demands are still very relevant today.

"Many African and Caribbean counties are still economically dependent on global superpowers and multinational companies, while here in the UK, black communities experience disparities in policing, education, employment and housing."

What happened next?

The next Pan-African Congress was not held until June 1974, when leaders and thinkers came together in Dar es Salaam in Tanzania.

By that point, 19 of the countries which had been the homeland for some of the delegates at the Manchester event had declared independence from the British Empire, joining the two which were already independent states in 1945.

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, who had helped to organise the first event in 1919, was the chairman in Manchester

In the decade after the Tanzania event, three more were independent.

Only Bermuda, which was represented in Manchester by members of its Workers' Association, remains a British Overseas Territory, self-governed by its own parliament under a governor who is appointed by King Charles III.

What is its legacy?

Harry said the event was "really radical" and showed "significant" levels of organising and activism which was "supremely empowering" but it "wasn't an "isolated piece of history".

"The most profound legacy of the congress is a call to action... encouraging us to build a more equitable, humane and respectful world," he said.

He said it also inspired people in the years which followed the conference, such as Kath Locke who co-founded the Abasindi Co-operative in 1980, an organisation based in Manchester's Moss Side which was established by and to benefit the black women in the community.

He said Makonnen became a "massive mentor" in terms of developing Locke's "political identity" and she went on to be a "really significant" person in the histories of the city's black communities.

Press coverage at the time used terms now considered offensive and failed to get nationalities correct

Maya said the congress "placed Manchester at the epicentre of global and successful liberation movements".

However, she added that there was a need to celebrate the city's radical history more.

"Apart from one plaque that was very hard fought... where the congress was held, there's nowhere else in the city where you can go and see any kind of physical legacies," she said.

She added that it was not evident in exhibitions and only occasionally taught in schools.

"Why do we not talk about it in the same breath as the Peterloo massacre when we talk about Manchester's radical histories?" she said.

How is it being commemorated?

There are a series of events to mark the 80th anniversary of the congress, including a discussion and networking event, external at what is now Manchester Metropolitan University's Grosvenor East building where the event took place.

The event will explore what liberation, self-realisation and self-determination looks like for communities and how the enduring legacy of the Pan-African Congress can inform collective action and cultural leadership in Manchester.

Manchester City Council is hosting a "deep dive talk, external" on 29 October at the Friends' Meeting House by Parise Carmicheal-Murphy along with the Ahmed Iqbal Ullah RACE Centre team to highlight the impact the conference has had on racial equality.

The trust will also host a talk, external at Central Library on 3 November to commemorate the anniversary of the Congress and its enduring relevance.

Get in touch

Tell us which stories we should cover in Greater Manchester

Listen to the best of BBC Radio Manchester on Sounds and follow BBC Manchester on Facebook, external, X, external, and Instagram, external. You can also send story ideas via Whatsapp to 0808 100 2230.

Related topics

- Attribution