Post office scandal helped infected blood campaign

Andy Evans was given infected blood when he was five years old

- Published

A victim of the contaminated blood scandal has said the recent public interest in the Post Office scandal has helped raise awareness of his fight for justice.

Andy Evans, from Evesham, in Worcestershire, contracted Hepatitis C and HIV when he was five years old from being given an infected product by the NHS.

He set up the Tainted Blood campaign in 2006 to campaign for the victims.

Mr Evans said: "People were talking about it within the media and they were drawing those parallels with the contaminated blood scandal."

A public inquiry, external, led by Judge Sir Brian Langstaff, is due to present its final report on 20 May.

It began in 2019 and aimed to examine the deaths of more than 3,000 people who died after contracting HIV or hepatitis C via NHS treatments in the 1970s and 80s.

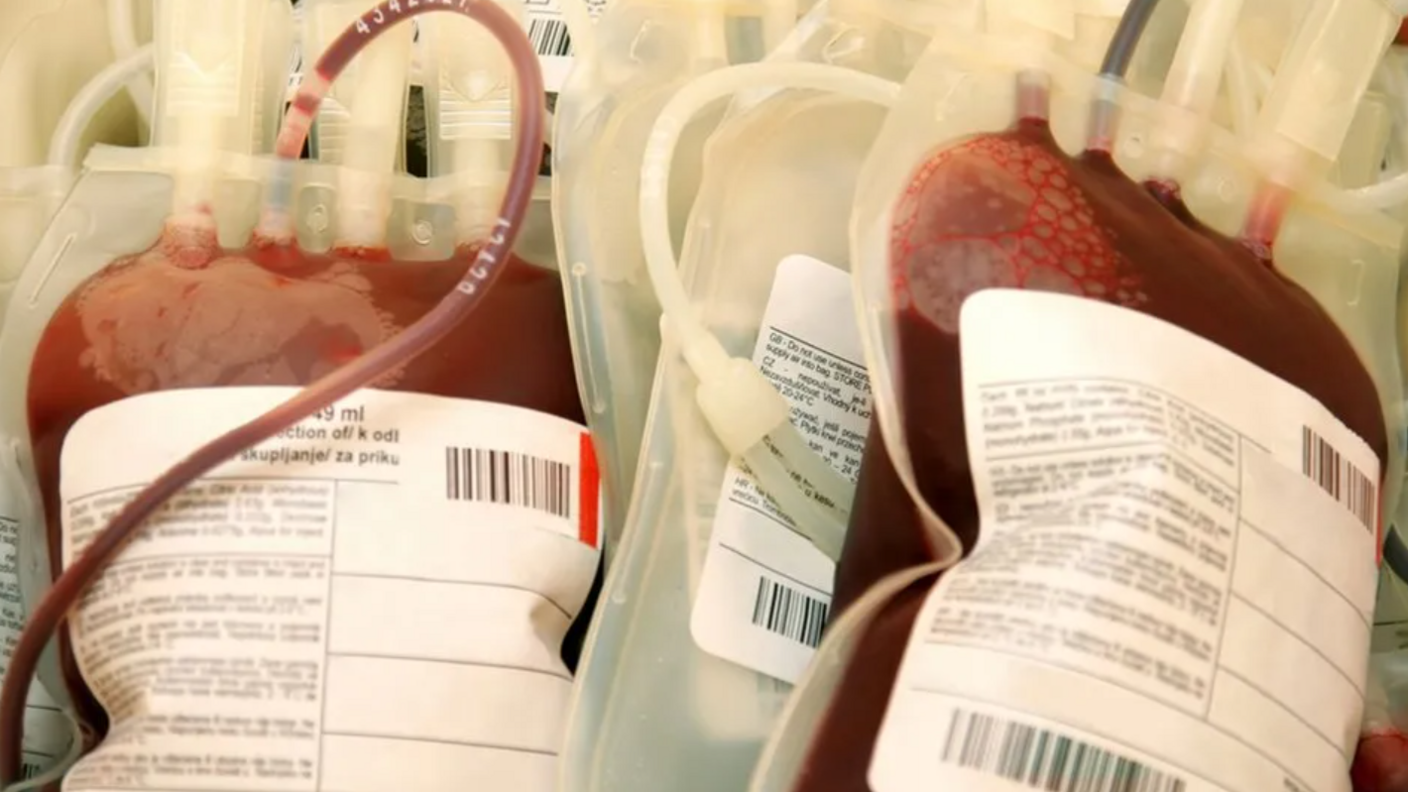

Patients with haemophilia and other blood disorders became unwell after being treated with factor VIII or IX.

The medication was imported from the US where it was made using pooled blood plasma from paid donors, some of whom came from high-risk groups including prisoners and drug-users.

An interim report stated that wrong was done on individual, collective and systemic levels and it is expected to definitively conclude whether medical ethics codes were observed.

Infected and unscreened blood donations in the 1970s were pooled and used in blood products

Mr Evans said it had been "an exemplary public inquiry" and said he hoped it would result in some form of financial compensation for victims.

"At this point for me and for many other campaigners we just hope to achieve vindication for everything we've been saying the decades up to the inquiry," he said.

Recently, the BBC has learned more about trials involving children with blood clotting disorders, where families had often not consented to them taking part.

Documents also show that doctors in haemophilia centres across the country used blood products, even though they were widely known as likely to be contaminated.

Mr Evans said: "The scandal itself is bad enough, but then you take into account the fact that people were genuinely experimented on without their consent, without their parents' consent."

He said it was "the story that people hear but they don't really believe is true".

"Hopefully the inquiry will dispel that myth that it wasn't true," he added.

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: newsonline.westmidlands@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published5 April 2023

- Published30 July 2022

- Published29 July 2022

- Published5 April 2023

- Published9 November 2022