Scottish blood victims were 'studied without knowledge'

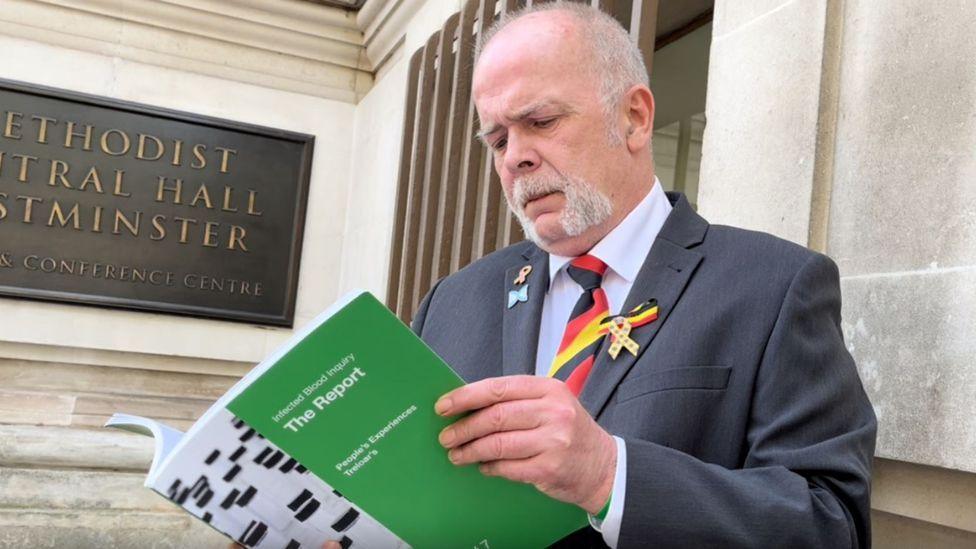

Bruce Norval, who was diagnosed with Hepatitis C in 1990, says the inquiry's report prompted feelings of vindication and anger

- Published

Scottish patients who were infected with life-threatening diseases after being given contaminated blood were studied without their knowledge, a landmark inquiry has found.

More than 30,000 people in the UK, including about 3,000 in Scotland, contracted HIV and Hepatitis C via contaminated blood products in the 1970s and 80s.

The Infected Blood Inquiry looked at services across the UK and found that many Scottish patients being treated for haemophilia were used for Aids research without their consent.

The Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service (SNBTS) apologised to victims ahead of the publication of the report.

Infected blood scandal victims betrayed by cover up, inquiry says

- Published20 May 2024

How did the infected blood scandal affect Scotland?

- Published20 May 2024

Blood transfusion boss apologises over scandal

- Published17 May 2024

The inquiry found that as Scottish doctors became aware of the risks of using a blood clotting treatment called Factor VIII, they did not inform their patients and instead carried out research.

Many became infected after receiving blood transfusions on the NHS, others through treatment for haemophilia.

Unlike in the rest of the UK, the vast majority of infections in Scotland came from blood donations from within the country.

Medics here did not have to rely on commercial products from the United States.

In the 1970s and 80s, the country was largely self-sufficient in blood products, while the Protein Fractionation Centre in Edinburgh had the capacity to process blood plasma to manufacture treatments for haemophilia or certain forms of immune deficiencies.

In his final report, inquiry chairman Sir Brian Langstaff said patients in Edinburgh and Glasgow were not initially informed about the risks of Factor VIII, with doctors instead opting to study the patients.

The report said the so-called “Edinburgh Cohort” was among the most studied group of patients in the world, because they were infected by a single batch of Factor VIII, under the care of Prof Christopher Ludlam.

The report concluded that his patients should have been told they were being studied, and about the results of the research, but they were “kept in the dark”.

Thousands of Scots were given contaminated blood in the 1970s and 1980s

Sir Brian rejected claims in Prof Ludlam’s evidence that the testing was for routine monitoring.

He said: “It was undoubtedly research, despite his suggesting otherwise.

"Patients were never informed of the results of the investigations and the studies led to no review of the treatment regime. It did, however, lead to publications in Dr Ludlam’s name and of his colleagues.”

He added: “Had they been informed… they would also have been told why, and would have become aware of the dangers of the treatment they were receiving.

"Some or all of them may then have refused to continue to be treated with concentrates. They may not then have been infected with HIV.”

Sir Brian concluded that Scotland’s work in the domestic manufacture of blood products, reducing reliance on commercial products imported from overseas, could have helped the whole of the UK reach self-sufficiency.

He said “a considerable number of cases of Aids would have been avoided, and, it follows, a significant number of deaths”.

Scottish Public Health Minister Jenni Minto has apologised to victims

But the inquiry chairman said it also led to some complacency among Scottish officials.

In May 1983, as news of the spread of Aids emerged in Europe, the Scottish Office’s principal medical officer Dr Archibald McIntyre told a senior civil servant that the situation did not "warrant action until the risks have been more fully evaluated” due Scotland’s near self-sufficiency in blood products.

No action or decisions were taken.

Sir Brian concluded that from early 1983 decision-makers in Scotland knew there was a real risk but, due to a lack of knowledge, their response was insufficient and too slow.

Bruce Norval was being treated for haemophilia when he was infected with Hepatitis C.

He has been at the forefront of campaigning since he received his diagnosis in 1990, having been infected a decade earlier in Edinburgh.

He said he felt he had been “lied to” from the moment he was diagnosed.

Mr Norval told BBC Scotland News the report prompted mixed feelings.

“Vindication of what campaigners have been saying for over four decades,” he said. “The anger is the 3,000 lives lost before the truth was told.”

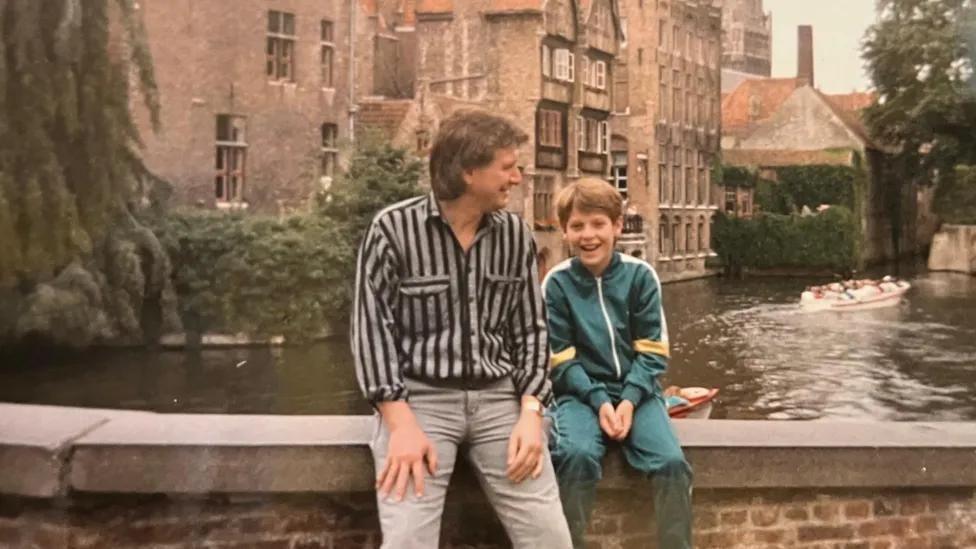

Euan McDougall, pictured with his dad John, died from Aids aged 16

John McDougall’s son Euan died from Aids in 1994 aged 16. He was infected with HIV during treatment at Yorkhill children’s hospital in Glasgow.

He said it was vindication after speaking about the scandal for 40 years.

"To actually arrive at this day and to have the report confirming what we’ve been saying - it’s vindication, that’s the main thing... It helps me."

The report described the treatment regime at Yorkhill as "utterly unacceptable".

Mr McDougall added: “Reading that it’s hard to think of a more damning phrase for a hospital and to that extent I feel vindicated.”

Joyce Donnelly, representing the Scottish Infected Blood Forum, said if the recommendations of the inquiry were implemented victims would receive what they should have received decades ago.

She added: “If the government can now put it right – a lot of people have missed out, a lot of people have passed on and died in the interim – but there are still people who are waiting for it to be put right and that is my hope for the future.”

Scottish Public Health Minister Jenni Minto apologised to those affected by the scandal.

"The Scottish government has already accepted the moral case for compensation for infected blood victims and is committed to working with the UK government to ensure any compensation scheme works as well as possible for victims."

She added that the government had set up an oversight group, including senior staff from NHS boards and charities representing those affected, to "consider the inquiry's recommendations for Scotland".

'Hiding of the truth'

Looking at the extent of the scandal across the UK, Sir Brian concluded there had been a cover up by authorities.

He said it was “not an orchestrated conspiracy to mislead” but there has been “a hiding of much of the truth”.

The inquiry reported “instinctive defensiveness, to save face and to save expense” that had ben a “collective failing of successive governments”.

The SNBTS had been criticised for not adequately screening donors and for taking donations from prisoners, which were known to be at at greater risk of infection due to higher levels of intravenous drug use.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, in a speech to the House of Commons, offered a “wholehearted and unequivocal” apology for the “terrible injustice”.

He said the UK government would provide "comprehensive" compensation - thought to total more than £10bn - to victims, with a statement to come on Tuesday.

Related topics

- Published8 May 2024