The woman who built an 'aidbot' for displaced people in Lebanon

Hania coded a chatbot to use on WhatsApp that helps displaced people in Lebanon

- Published

Last autumn Hania Zaatari, a mechanical engineer who works for Lebanon's Ministry of Industry put her skills to use as war in the country raged on. Hailing from Sidon, South Lebanon, she created a chatbot on WhatsApp that simplified access to much-needed aid.

"They lost their houses, their savings, their work, everything they had built," Hania says, referring to those forced from their homes by war.

On 23 September, Israel dramatically escalated its offensive against the Lebanese armed group Hezbollah, with which it had been fighting a spiralling conflict since Hezbollah attacked Israel in October 2023.

According to the Lebanese government, at least 492 people were killed in one of Lebanon's deadliest days of conflict in almost 20 years.

Thousands of families fled to Sidon after the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) hit what it said was 1,600 Hezbollah strongholds inside Lebanon.

Hania says many displaced people sought shelter in schools and other public buildings, but many others who fled their homes were forced to rent elsewhere or stay with members of their family.

It is these people who weren't directly receiving support from the government that she wanted to help. Drawing on her programming skills, Hania created the "aidbot" to narrow the gap between the demand and supply of aid.

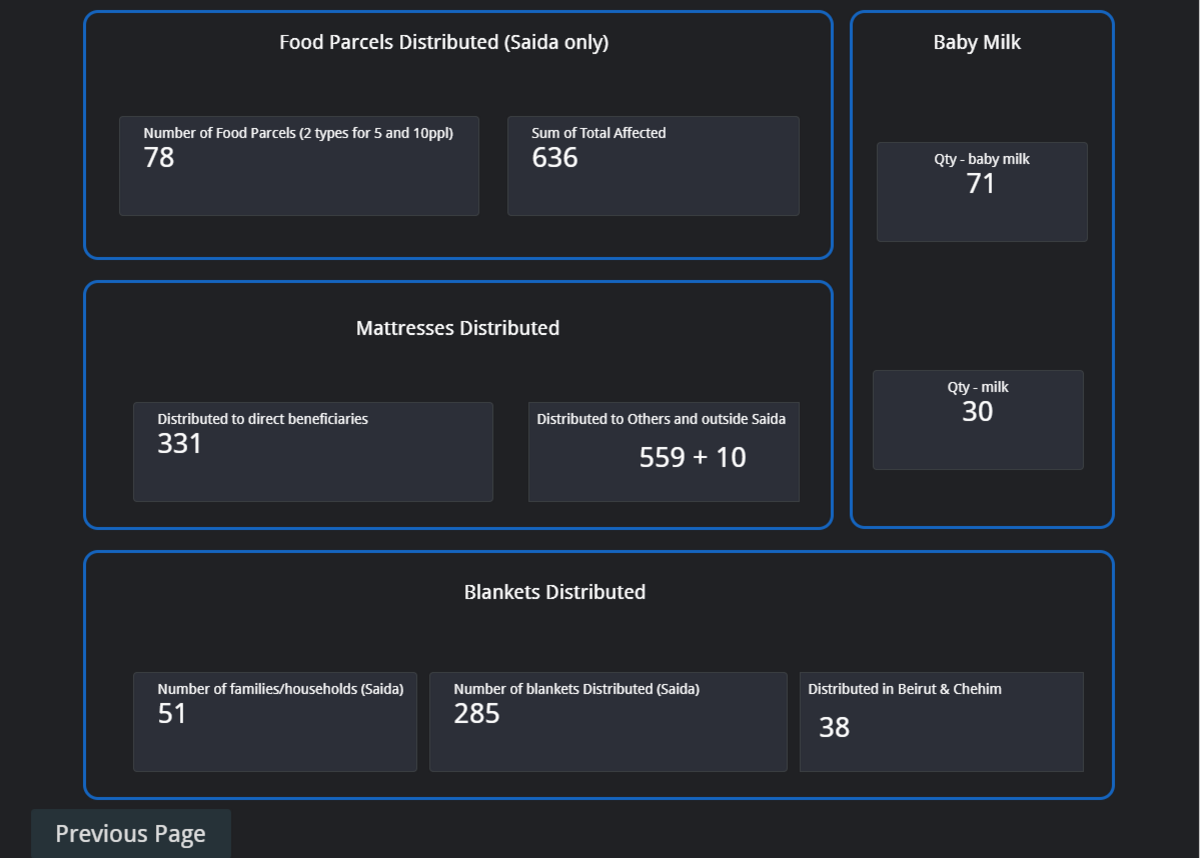

A publicly available dashboard records expenditures, donations as well as what aid is being distributed

The aidbot is a chatbot - a type of AI system designed to communicate with its users online - that links to WhatsApp. It is programmed to ask simple questions about the types of aid people require along with their names and locations.

This information is then recorded onto a Google spreadsheet which Hania and her team of unpaid volunteers, made up of friends and family, access to distribute aid such as food, blankets, mattresses, medicine and clothes.

Hania used her spare time to build the bot using the website Callbell.eu, which is commonly used by businesses to engage with customers on Meta's platforms such as WhatsApp, Instagram and Facebook messenger.

She explains that the bot, which is still being used today, makes distributing aid more efficient as it cuts down the amount of time she spends responding to requests for aid over WhatsApp.

"I'm not really interested in knowing their names. I just need to know where they are so I can manage the delivery," she says.

Take, for example, a request for baby formula. Hania says the bot will ask for the age of the baby and the quantity needed so that she and her team can provide it.

The project, she says, is funded by donations coming from Lebanese people living abroad. She's created a publicly available dashboard to record what the project has spent money on and how much aid she and her team have distributed.

At the time of writing they have delivered 78 food parcels to families of 5 or 10 people, 900 mattresses, and 323 blankets across Sidon and other parts of Lebanon.

Before and after Khaldoun's home was hit by an Israeli strike

Last October, 47 year-old Khaldoun Abbas and his family fled their homes in Najjarieh after they received calls from the IDF urging them to leave for their own safety.

Seventeen people, ranging in age from nine to 78, slept under one roof in a rented three bed apartment in Sidon.

Khaldoun says he, his wife and their children, as well as his brother's family slept on mattresses they requested using the aidbot in the hallway of the flat. They also requested blankets, food and cleaning detergents.

Unlike his neighbours, he's not been able to return to his home. It was destroyed in a confirmed Israeli strike 11 days later. The IDF told the BBC it "struck a terror infrastructure".

When we put this allegation to Khaldoun, he denied having any connection to Hezbollah or any other party.

What is Hezbollah and why is Israel attacking Lebanon?

- Published14 February

Israel-Hezbollah conflict in maps: Ceasefire in effect in Lebanon

- Published27 November 2024

Lebanon's financial crisis explained

- Published5 August 2020

"This isn't the first time Sidon has opened its doors to displaced people," Hania explains, referring to the wave of people who have arrived in the city.

Sidon has a long-standing reputation for taking in internally displaced people driven from their homes along the Lebanon-Israel border.

The most recent conflict began in October 2023 after the war between Israel and Hamas spilled over into Lebanon when Hezbollah, Hamas' ally, fired rockets into Israel in support of Gaza.

The Lebanese healthy ministry says nearly 4,000 people have been killed and over a million have been displaced. The ministry does not say how many of these are civilians or combatants.

In Israel around 60,000 people have been evacuated from Northern Israel and authorities say more than 80 soldiers and 47 civilians have been killed.

Hania has been ordering mattresses from Syria.

Last November a ceasefire was agreed between Israel and Lebanon. Despite some skirmishes it has largely been upheld. But people on the ground say the provision of aid has not improved.

International NGO Islamic Relief told the BBC that the "conflict, destruction, and evacuation orders have fuelled ongoing displacement in Lebanon which has made it difficult to assess and address the needs of the population amid the changing situation."

But it is not just the war that is hindering aid distribution.

Bilal Merie, a volunteer working with Hania says many of the problems they face are due to the "high demand but short supply" of aid.

He puts it down to the deep economic turmoil that has gripped the country since 2019, meaning the Lebanese government has had to rely heavily on funding from creditors and aid organisations for goods.

But even NGOs are feeling the crunch. Unicef Lebanon says that with only 20% of the funding they need, it "continues to face an enormous funding gap," meaning the charity is unable to support families when they need it most.

In a country overrun with financial woes and by war, could this aidbot make a tangible difference?

It is the first time researcher John Bryant from the think tank Overseas Development Institute has heard of a chatbot being used in such a way in the humanitarian sector.

He says the cultural context in which it is being used is commendable. That is, with knowledge of "the channels people are using to talk to each other and meeting them in their own language".

However he is unsure of its scalability, as what works in Lebanon cannot easily be replicated in other parts of the world.

"What tech offers a lot of the time is a standard cookie cutter approach.

"It's the local designers, the local translators, the trusted human interlocutors and elements within that system that elevate digital tools into something useful," he says.

The aidbot might not be able to offer the solution to all Lebanon's problems, but to the families using it, it has made life a little easier.

Additional reporting by Ahmed Abdallah