Six things that may cost Americans more after Trump's tariffs

- Published

In April, US President Donald Trump announced he was introducing sweeping new tariffs, extra taxes that importing firms have to pay if they bring in goods from abroad.

Since then some of the US's major trading partners including the UK, Japan and now the European Union have negotiated down the headline tariff rates. The EU's agreement cuts in half the 30% tariff Trump had threatened.

But other countries are still facing higher rates, including Canada, which sees tariffs rise to 35% as the 1 August deadline passed.

Trump says the extra tariffs will generate billions in revenue and encourage firms to manufacture in the US to avoid the taxes.

But there are already signs that the levies may be pushing up prices for American consumers and economists argue that there is still some way to go before American shoppers feel the full force of the rises.

So what products are likely to become more expensive?

Clothing and footwear

The vast majority of clothing and footwear sold in the US is made in other countries, including the manufacturing hubs of Vietnam, China and Bangladesh.

Though Trump has backed down from the steepest tariffs he initially threatened, the taxes on imports from those countries are still sharply elevated.

Under current plans, the US is charging at least 30% on goods made in China, with plans to start collecting taxes of 19-20% on items from countries such as Vietnam, Bangladesh and Indonesia on 1 August.

The measures are putting pressure on major US department stores like Target and Walmart, where Americans often turn for affordable clothing, as well as big-name apparel brands, such as Levi Strauss and Nike, which have said they will raise prices for certain items.

After months of declines, apparel prices jumped 0.4% from May to June. Overall, the Budget Lab at Yale, which monitors the impact of government policy on the economy, expects clothing prices overall to surge a shocking 37% in the short run.

Coffee, olive oil and other food

Almost all of the coffee consumed in the US comes from outside the country, meaning it could soon become a bigger burden on Americans' wallets.

Coffee from Brazil is facing 50% tariffs, Vietnamese coffee is likely to be subject to a 20% tariff.

With 15% tariffs in place on products from European Union nations, the prices of shelf staples such as Italian, Spanish or Greek olive oil could rise.

Trump has separately raised tariffs against Mexico, a major supplier of items such as tomatoes and avocados, though he has granted some key exemptions to those levies.

Still the Budget Lab at Yale estimates that food prices will rise 3.4% in the short-run, with fresh produce seeing a particularly sharp jump initially.

Beer, wine and spirits

The US is one of Europe's biggest alcohol export markets, with European companies, including Pernod Ricard and LVMH, selling €9bn (£7.8bn) of alcohol to the US each year. The country makes up about a third, external of Irish whiskey exports and almost 18% of champagne exports.

However, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has not said whether alcohol will be included in its tariff deal with the US or exempted along with other, unspecified, agricultural and food products.

Meanwhile, under tariffs announced in April, Mexican beers like Modelo and Corona are expected to become more expensive because of levies on aluminium, which affects beers poured from cans. Most beer in the US - 64.1% - is served out of cans, according to the Beer Institute.

Cars

Trump has been particularly keen to see tariffs on imported vehicles in the hope that raising the price of foreign-made cars will give a boost to American firms.

In March, he introduced a 25% levy , externalon imported passenger vehicles and parts in an effort to "protect America's automobile industry".

He has since reduced this to 15% for cars from some key exporters, including the European Union and Japan. Importers will pay 10% on UK cars.

The tariffs have not led to a sharp rise in car prices, external so far.

Erin Keating, an executive analyst Cox Automotive, suggests that is because firms are so far "absorbing more of the burden [from tariffs] and not passing the added costs to consumers".

But as costs mount, it's unclear how long that position will hold.

Trump's hopes that the tariffs will boost sales by US companies may also backfire.

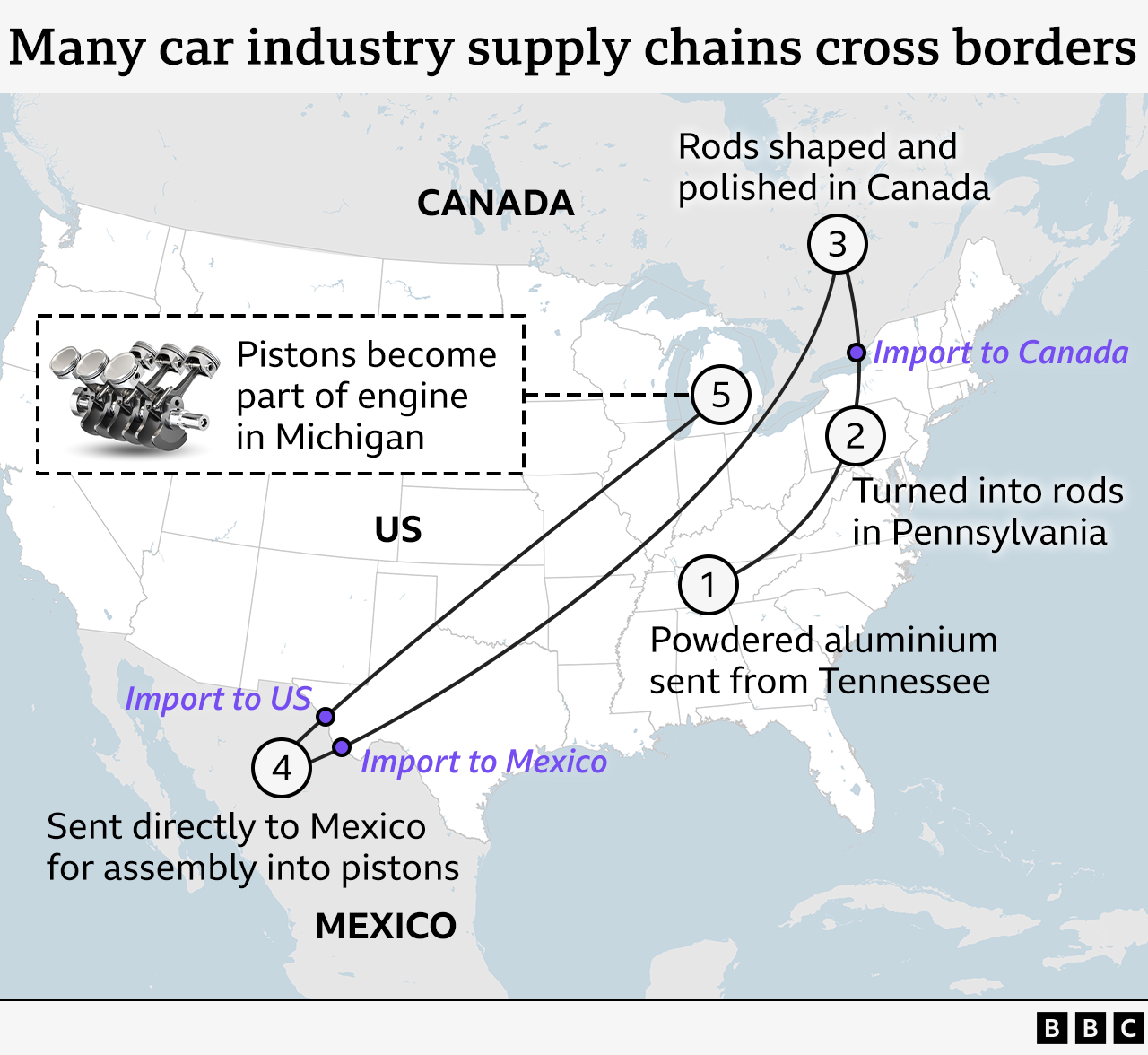

That's because many cars made in the US rely on parts or materials from overseas. Some brands sold by US companies are also assembled outside the country, including in factories in Canada and Mexico, meaning they are subject to the 25% levy. Those are now at a disadvantage compared to offerings from key foreign competitors.

Houses

After Trump raised tariffs on steel and aluminium earlier this year, prices for steel in the US increased. A 50% levy on copper is now set to start on 1 August, while Trump has also threatened tariffs on lumber.

All three are key materials used to build homes.

The National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) in the US has warned that the measures could increase the cost of building homes - which are mostly made out of wood in the US - and also put off developers building new homes.

"Consumers end up paying for the tariffs in the form of higher home prices," the NAHB said.

Just how much may depend on whether Trump resolves his trade dispute with Canada, one of the biggest suppliers, currently facing potential tariffs of 35%.

The US buys about 69% of its lumber, 25% of its imported iron and steel, and 18% of its copper imports from Canada, a report by the Canadian Chamber of Commerce has suggested.

Energy and fuel

The European deal will increase the amount of energy Europe buys from the US, which von der Leyen said , externalwill "replace Russian gas and oil" with cheaper liquefied natural gas (LNG), oil and nuclear fuels from America.

But the tariffs don't necessarily mean good news for US consumers.

Generally speaking, Trump has made oil and gas imports exempt from tariffs.

But he has put a 10% rate on energy exports from Canada, America's largest foreign supplier of crude oil. According to official trade figures, 61% of oil imported into the US between January and November 2024 came from Canada.

The US doesn't have a shortage of oil, but its refineries are designed to process so-called "heavier" - or thicker - crude oil, which mostly comes from Canada, with some from Mexico.

"Many refineries need heavier crude oil to maximize flexibility of gasoline, diesel and jet fuel production," according to the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers.

That means if Canada decided to reduce crude oil exports in retaliation against US tariffs, it could push up fuel prices.

Follow BBC's coverage of US tariffs

LIVE UPDATES: Follow the latest updates and analysis

EXPLAINER: What tariffs has Trump announced and why?

Additional reporting by Lucy Acheson