A boy with HIV and his sisters' fight for justice

Rob Gibbs just wanted to live a normal life, his sisters said

At a glance

Rob Gibbs died with Aids in 1991 after he was treated for haemophilia with infected blood

His twin sisters say they nursed him at their Devon home during his final weeks

They are among thousands of victims seeking justice during an inquiry into the infected blood scandal

- Published

The only wish that twin sisters Meg Parsons and Liz Gardner had when they were growing up by the East Devon seaside was for their big brother not to die.

Rob Gibbs was diagnosed with HIV at 14 after his haemophilia, a rare blood-clotting disorder, was treated by the NHS with contaminated blood plasma.

He died with Aids aged 21, nursed in his final weeks by the siblings who had so longed for his survival.

As an inquiry into the blood contamination scandal draws to a close, his family have told of their battle for justice.

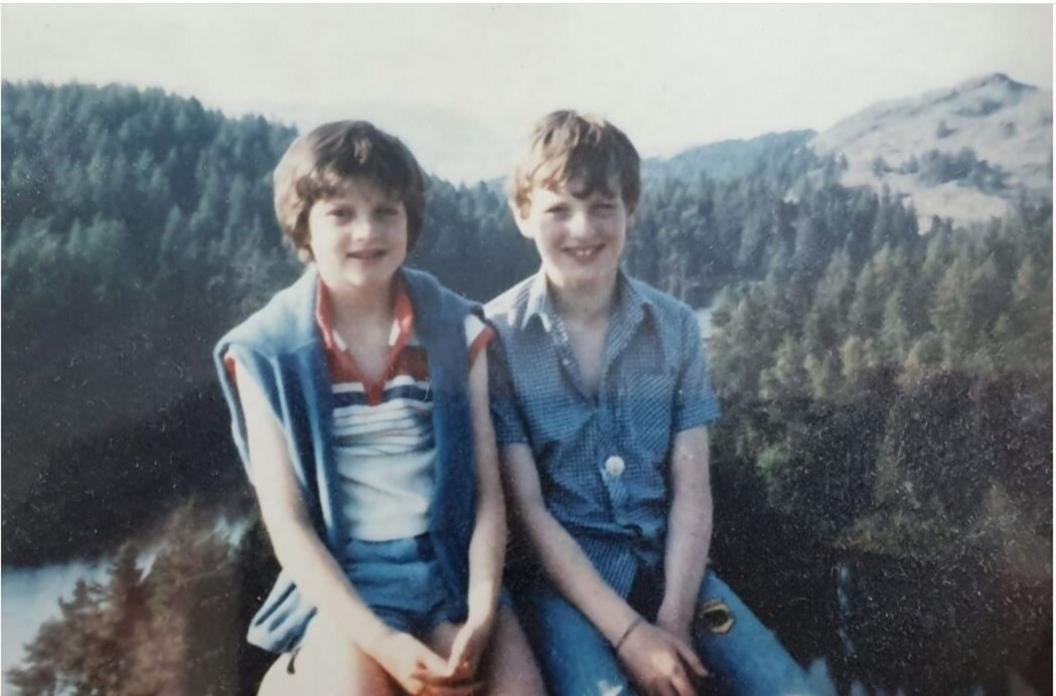

Liz and Meg aged 15 and Rob aged 17 on holiday in Spain

Mrs Parsons said: “When you have a childhood trauma it stays with you through your whole adult life.

“I want to know the truth."

More than 30,000 people in the UK were infected with HIV and Hepatitis C after being given contaminated blood products during the 1970s and 1980s.

A public inquiry into what has been called the biggest treatment disaster in NHS history will announce its findings in May.

Mrs Parsons and Mrs Gardner, now 51 and still living in Devon, are among those campaigning for compensation.

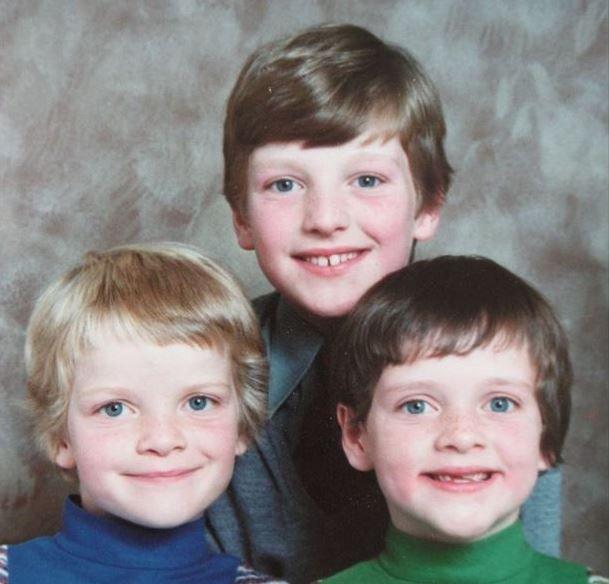

The three children before Rob's diagnosis with HIV

Diagnosed with haemophilia at the age of two, Mr Gibbs was initially treated with cryoprecipitate, made from blood plasma from one donor and administered in hospital, Mrs Parsons told the BBC.

In the Seventies, new treatment Factor VIII became available to replace the missing clotting agents, made by pooling plasma from multiple donors, and imported from America.

It could be “administered at home”, Mrs Parsons said, which was “revolutionary” for patients like Rob - who just wanted to "live a normal life".

But whole batches were contaminated with deadly viruses.

The infected blood inquiry estimates that 1,250 people with bleeding disorders in the UK developed both HIV and Hepatitis C as a result, including 380 children.

In October 1984, at the age of 14, a blood test, which Mrs Parsons said was non-consensual, revealed Mr Gibbs had HIV.

Read more on the infected blood inquiry

The sisters have attended the blood contamination inquiry

A consultant delayed telling the family and it was not until six months later, during a routine appointment, that Mr Gibbs learnt of his diagnosis.

It was thought he was likely to have contracted the virus at about the age of nine.

It was only later they found out he also had Hepatitis C.

For the family, including the 12-year-old twins, the devastating diagnosis and its delay were "traumatic".

Mrs Parsons said she remembered feeling “absolutely stunned” that their brother had a “terminal illness with no cure”.

They kept the truth from their friends, she said, adding: “We weren’t offered any counselling.

"Our lives just changed.

“It was just an awful, awful time.

“My mum was administering his injections at home.

"We were living together as a family… we were potentially at risk during that time.”

The government ran an advert featuring a tombstone to raise awareness of the disease, Mrs Parsons said, and when it came up on television, the family would “sit in silence”.

She added: “We never, ever discussed what happened as a family. It was just way too painful.

“We went on lots of holidays, making lots of lovely memories and things.

“My school friends didn’t know but I started having things like night terrors.

“My only wish as a child was for Rob not to die."

Mrs Gardner, Mrs Parsons' twin sister, said it was only years later that they realised that during every family roast, when handed the wishbone, they were silently praying for the same thing.

"For Rob not to have Aids, for him not to die," she added.

The sisters both wished for the same thing when handed a wishbone during family roast dinners - for their brother not to die

Aged 17, and after a cancer diagnosis signalled he had developed Aids, Mr Gibbs' condition worsened, Mrs Parsons said.

He died at home in 1991, three days before the twins' 19th birthday, with the sisters caring for him in his final weeks.

“There was no palliative care, there was no counselling," added Mrs Parsons.

Rob had been "at peace" when he died, his sisters said, selecting meaningful songs for his own funeral and telling them to "live their lives to the full".

"But he thought he was just unlucky, he never realised the scale of what had happened," Mrs Parsons added.

Afterwards, the sisters said, they returned to university with the loss of their brother “buried deep”.

Mrs Gardner added: "It wasn’t until the inquiry opened that we started to find out the numbers and the scale.

"It's been almost like a second wave of shock to get your head around that."

She said they also learned that the risks around imported blood products were known – and they were administered anyway.

Meg remembers wishing for her older brother 'not to die'

Mrs Gardner added: "The NHS was sending mums off with bottles to put in a fridge and inject their children.

"I can picture Rob at the kitchen table being injected - and now we know what we were witnessing.

"My son is about to turn 18 which is the age Robert was when he had the first sign that HIV was developing into Aids.

"Every government has kicked this can down the road."

In 1991, when her brother died, the family received £40,000 from the government and they were told at the time they could not pursue further litigation, Mrs Parsons said.

"The whole of the scandal has just been dealt with so badly by medical staff, hospitals, haemophilia centres and the government. It's just been absolutely scandalous.

"This is a tragedy that could have been avoided."

A government spokesperson said: “This was an appalling tragedy, and our thoughts remain with all those impacted.

“We are clear that justice needs to be delivered for the victims and have already accepted the moral case for compensation.

“This covers a set of extremely complex issues, and it is right we fully consider the needs of the community and the far-reaching impact that this scandal has had on their lives.

"The government will provide an update to Parliament on next steps through an oral statement within 25 sitting days of the Inquiry’s final report being published."

Follow BBC Devon on X (formerly Twitter), external, Facebook, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to spotlight@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

More stories on the infected blood scandal

- Published7 March 2024

- Published28 February 2024