'I want my brother’s infected blood death recognised'

Janine Jones said she wanted her brother, Marc Payton, to be recognised through the publication of the final report into the infected blood scandal

- Published

Fighting for justice for her brother is all Janine Jones has known for the past 21 years.

Her sibling, Marc Payton, was infected with HIV and hepatitis C as a child in the 1970s after being treated with infected blood products.

He died aged 41 in 2003 and a final report into the infected blood scandal is due to be published on 20 May.

“I want my brother’s death recognised," Mrs Jones, from Bromsgrove, Worcestershire, said.

“Every haemophiliac in this country that’s died has not been recognised yet. It’s just absolutely scandalous.”

Marc Payton died at the age of 41 in 2003

Mr Payton was born in 1961 in Coleshill, Warwickshire and his parents, Ron and Val, noticed early on he would bruise easily and his legs would swell.

He was diagnosed at 10 months old with haemophilia and Mrs Jones said he "really suffered with his knees".

"I’ve got memories of him screaming out in the middle of the night in pain and mom having to get up and drive him into the hospital," she added.

When he was 11, he was sent to Treloar's College in Hampshire, a boarding school for physically disabled children with a specialist NHS haemophilia centre on site.

It was here that Mr Payton and other pupils were given treatment using blood products which were contaminated with HIV and hepatitis.

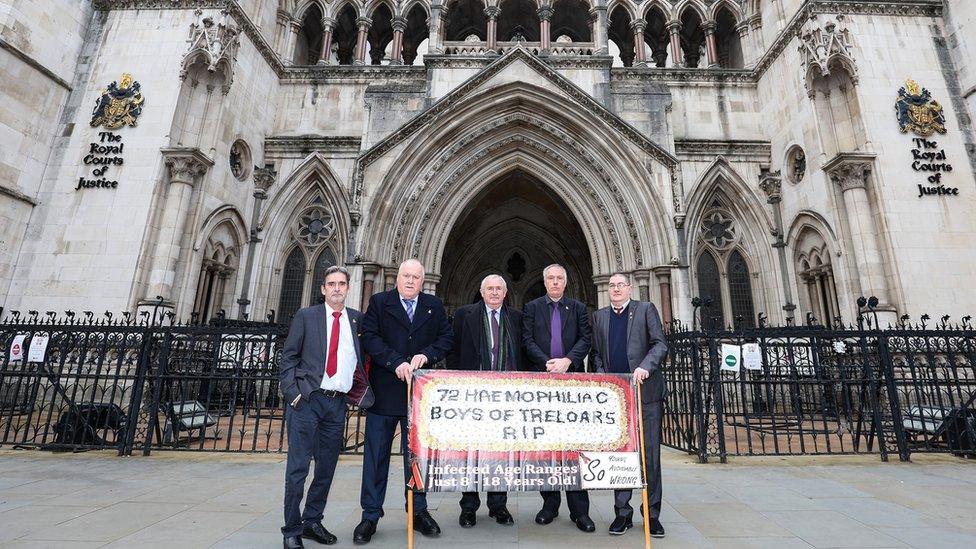

Dozens of haemophiliacs who attended the school from 1974 to 1987 have died after having the infected treatment.

Survivors and families, including Mrs Jones, are seeking damages from the college.

A spokesperson for Treloar's said it could not comment on the legal action "but we will continue to co-operate with the public inquiry into these issues and await its outcome".

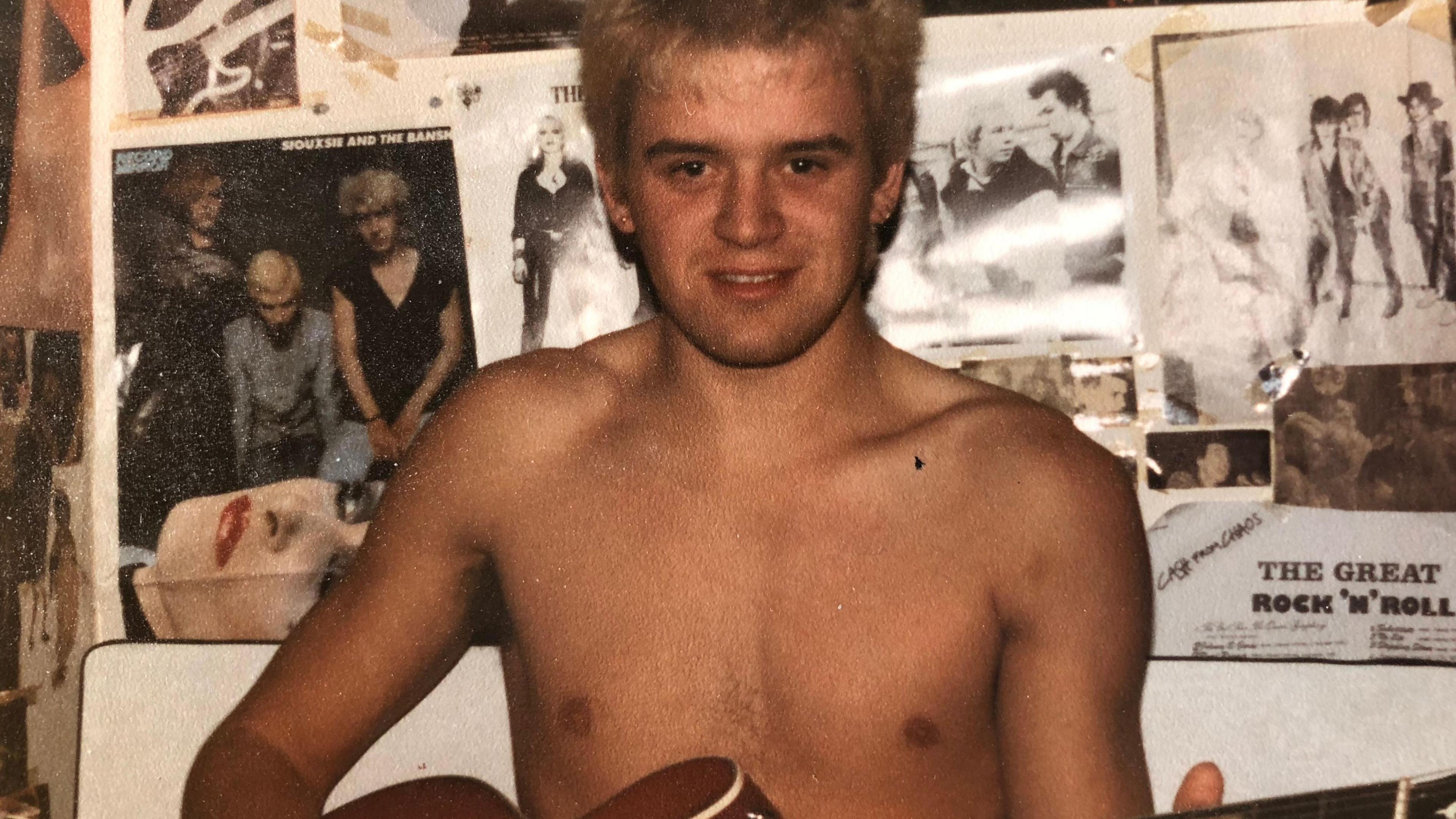

Before his HIV diagnosis, Mrs Jones said her brother was passionate about music and was a member of several bands

After he left the college, Mr Payton moved back to the Midlands and worked as a gardener for the University of Birmingham.

He indulged his passion for music, becoming a punk and joining several bands, and his sister said it was happy time.

But in 1985 his world came crashing down when he was told in a hospital appointment he had HIV, Mrs Jones said.

The diagnosis was devastating as "he was 23, newly engaged to his girlfriend" and planning on getting married and having children, she added.

"He couldn’t do any of that. He got married but couldn’t have children, couldn’t get a mortgage, cos he couldn’t get insurance because he was HIV positive.

“Mom went to pieces. She always blamed herself for him having haemophilia because she was the carrier."

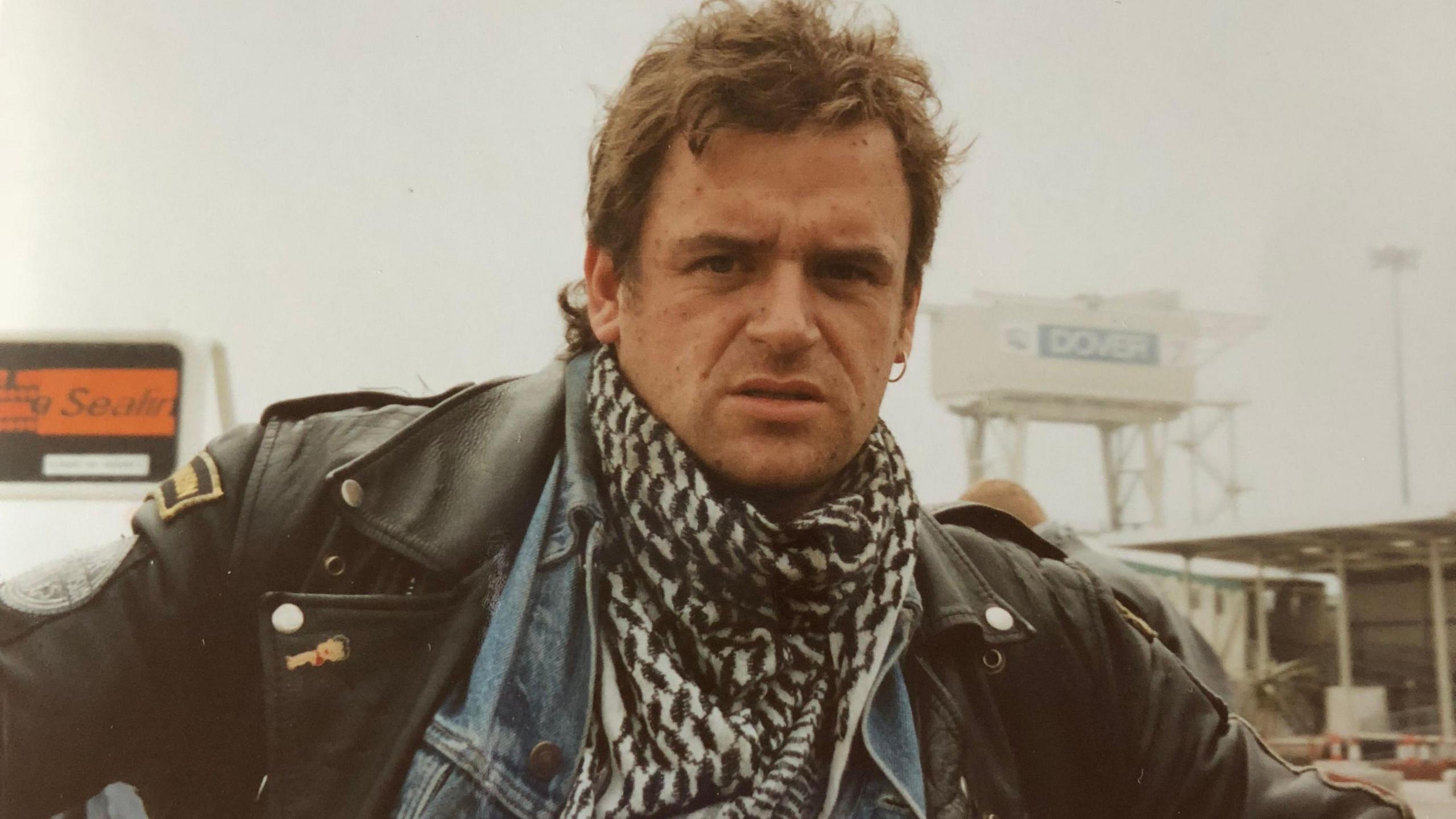

Six years after his HIV positive diagnosis, Marc Payton was told he had hepatitis C

In 1991, Mr Payton was told he had hepatitis C and his sister said treatment was tough; he could only work part-time and had health issues and bouts of depression.

During the 1990s he also underwent surgery and treatment for testicular and liver cancers.

Mrs Jones said his first marriage and a second one fell apart, and her brother attempted to take his own life twice before his death in 2003.

“For mom and dad to stand there and watch their firstborn die, I don’t think they ever got over it to be honest," she said.

"My sole priority [since his death] has been this, it’s been campaigning, finding out information. It’s an awful long time it really is."

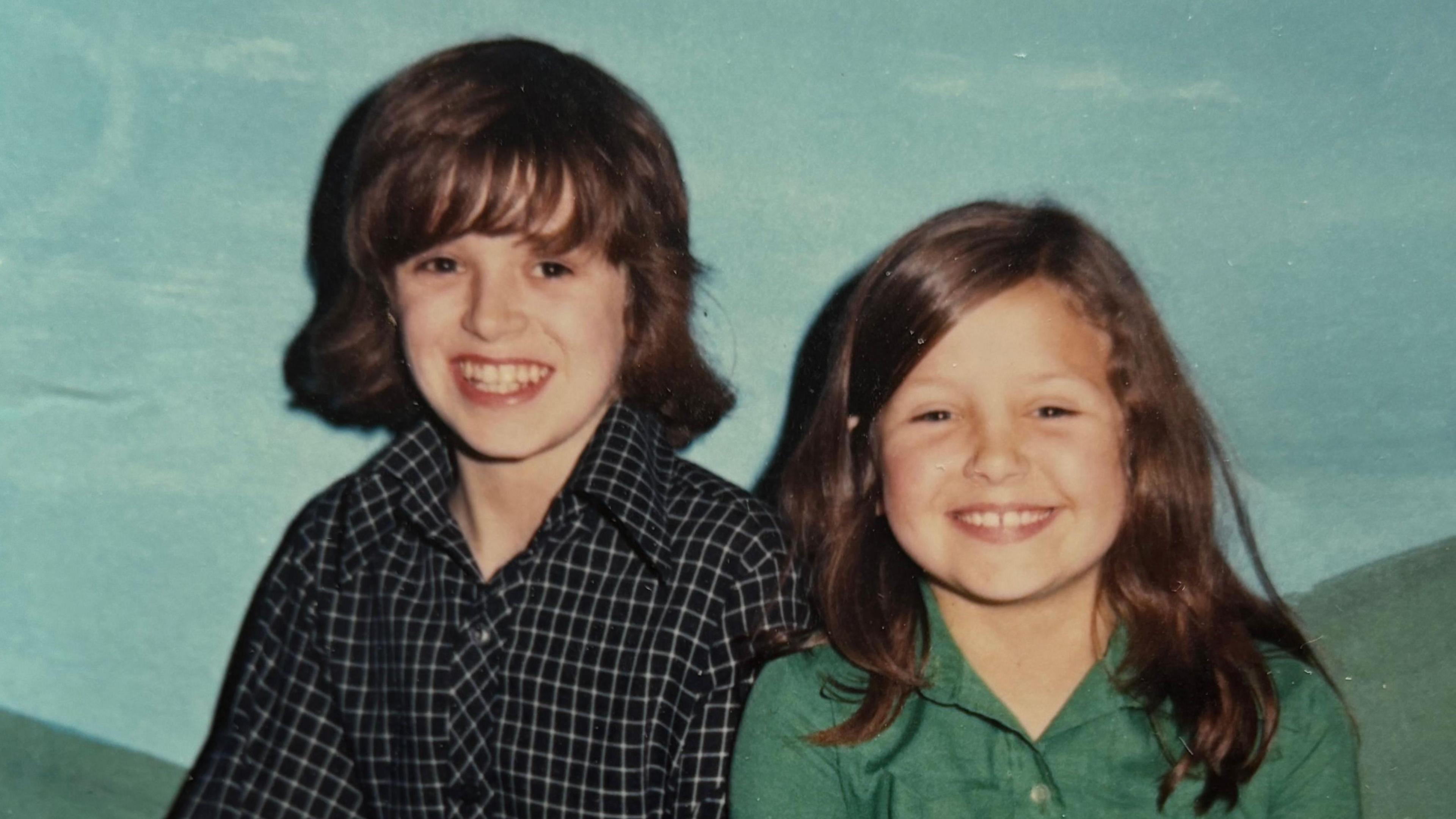

Janine Jones said she did not believe her parents ever got over her brother's death

Mrs Jones said she hoped the truth of what happened to her brother and others would finally be acknowledged in May and she thought the report would be "so damning".

"I’d like people held accountable [for what they’ve done] but I know this will never happen in this country, despite it happening elsewhere," she added.

Justice needs to be delivered for the victims of the infected blood scandal, a government spokesperson said.

Parliament would be updated on their next steps "within 25 sitting days of the inquiry’s final report being published", they added.

If you have been affected by any of the issues raised in this story you can visit BBC Action Line.

Mrs Jones (pictured, centre) said her life since Mr Payton's death had been consumed with campaigning for the truth to be told

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: newsonline.westmidlands@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published14 April 2024

- Published30 September 2022

- Published24 January 2022