Five new things about online campaigning

- Published

Pro-Jeremy Corbyn Facebook posts got huge traffic in 2017. How might things be different in the upcoming European elections?

What has changed online since the UK's last nationwide election?

Labour did surprisingly well in the 2017 general election, and social media probably played a role - or at least indicated something amiss in pre-election polls.

Pro-Jeremy Corbyn messages went viral online - particularly on Facebook - and were seen and shared by far more people than Conservative ones.

Later this month the UK will hold European Parliament elections. What should we be looking out for online - and what has changed in the last two years?

1) Facebook's algorithm

In the last general election, the Conservatives lost the Facebook war

In 2017 the Conservatives spent more than on Facebook advertising than Labour. But lists of most-shared stories, external on the most popular social network were dominated by posts sympathetic to Labour and hostile to Theresa May's party.

Instead of Labour relying on paid advertisements to push their messages, supporters were sharing them for free.

However, in the upcoming European Parliament elections, it might be harder for posts in support of Labour - or any other party - to spread quite so far or fast.

That's because at the start of 2018, Facebook announced a change to its algorithm, the code that decides what posts are given priority in your News Feed.

Chief executive Mark Zuckerberg chose to prioritise "posts from your friends and family" and make posts from "businesses, brands and media" less prominent.

It changed the media landscape overnight, with many publishers, particularly video sites, struggling to retain traffic. In the political world, the algorithm change particularly affected, external pro-Labour sites like Novara Media, the Canary and Skwawkbox.

During the 2017 campaign some posts got tens of thousands of shares on Facebook but given the algorithm changes - along with the usual ebb in political engagement outside of general elections - it's highly unlikely that these numbers will be reached in 2019.

Mark Zuckerberg's company has faced increased scrutiny

2) Pivot to privacy

For years the focal point of Facebook has been the News Feed, but this has recently been the source of scandals, with misinformation or "fake news" going viral on the platform. The company has also faced a criticism over revelations about Cambridge Analytica.

Facebook recently announced a strategic change of direction to address these concerns.

On 6 March chief executive Mark Zuckerberg announced that "privacy-focused communications" would become more important than "open social networks" in the future.

The new plans include adding end-to-end encryption to all messaging services, "reducing the permanence" of content posted on Facebook, and merging elements of Facebook Messenger, Instagram and WhatsApp.

More broadly, there are indications that political conversations in the UK increasingly take place within closed groups on Facebook and WhatsApp, where people can discuss issues with like-minded people in a semi-private format.

However this comes with risks - closed groups can become incubators for offensive content, such as Islamophobia in pro-Conservative groups, and anti-Semitism in pro-Labour ones, external.

During recent election campaigns in Brazil and India, misinformation spread rapidly in WhatsApp groups.

And in closed groups it is much harder for regulators, researchers and journalists to observe what is going on.

3) Facebook's ad archives

In one key way, Facebook has moved to increase transparency, through its political advertising archive.

The aim is to shed light on so-called "dark ads" - messages targeted at particular groups, but which are all but invisible to people outside of the target audience.

For instance, during the 2016 EU referendum, the official Vote Leave campaign spent more than £2.7m on targeted ads on Facebook.

The ads were viewed more than 169 million times - Facebook eventually released them to the general public, two years later.

"Dark ads" were also a key feature of the 2017 election campaign, with Labour, Conservatives, Liberal Democrats and other parties targeting groups of voters. A number of organisations and media outlets - including the BBC - urged voters to send in examples of political advertising they were seeing in their feeds.

VIDEO: How online advertising affects political campaigns

The new ad archive, launched last year, makes that job easier. New rules mean people posting political ads must prove their identity and location. And it's now possible to browse the database of political ads and view a demographic breakdown of people who have seen a particular advert.

We still do not know much about ads posted on other social media sites, although Google has introduced an ad archive, external for the upcoming elections. Last year a BBC investigation revealed the government and the pro-Brexit group Britain's Future were both buying up Google ads to secure the top spot when people search for the phrase "What is the Brexit deal?"

Examples of Brexit ads - both for and against - on Facebook

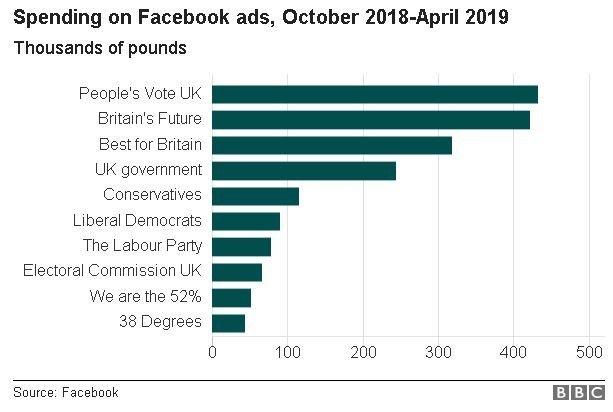

Thanks to Facebook's archive, we know for example that pro-EU campaign groups have spent more money on Facebook advertising than pro-Brexit ones since last October.

But while the ad archive identifies the person or group behind the ad, it doesn't mean that we know exactly where their money is coming from. And researchers have criticised, external the system for providing no information on who the advertisers meant to target - rather than who was reached - and for not being completely comprehensive.

So while we know more about online political ads than we did in 2017, there is still plenty we don't know.

4) Pressure on the tech giants

Aside from the world of politics, Facebook, Twitter and Google have been accused of neglecting user privacy and providing platforms for misinformation, hate speech and other damaging content.

One case in particular has become a rallying point for critics of the big social media giants.

After British teenager Molly Russell took her own life in 2017, her family looked at her Instagram account and found distressing material about depression and suicide.

Molly Russell's father said that Instagram is partly to blame for his daughter's death

In April the government released proposals for websites to be fined over "online harms". The proposals are also aimed at curbing terrorist content, child sex abuse and the sale of illegal goods.

Labour has said the plan doesn't go far enough, while in the US presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren has gone as far as saying the big social media giants should be broken up.

The 2019 European Parliament elections will out against a very different public mood compared to the very recent past. Fierce criticism of Facebook and Google has now gone mainstream.

5) YouTuber candidates

Mark Meechan makes YouTube videos under the name 'Count Dankula'

Celebrity politicians are nothing new.

As you may have heard, in 2016 a TV star got elected president of the United States, while more recently, another became president of Ukraine.

But what is new in this year's European Parliament elections is that internet celebrities are running for office. Two of UKIP's candidates gained fame through their controversial YouTube channels - Carl Benjamin, aka "Sargon of Akkad" and "Count Dankula", real name Mark Meechan.

Last year, Meechan was convicted of a hate crime and fined £800 after recording a pet dog giving Nazi salutes and posting it on YouTube. He was also the subject of a recent BBC Scotland investigation which found he was a prominent user of an online forum that contained racist language and threats against ethnic minorities.

Last week police said they were investigating a complaint against Benjamin, who in 2016 tweeted at Labour MP Jess Phillips: "I wouldn't even rape you... feminism is cancer."

They may be the among the first YouTubers to run in a nationwide election, but it's safe to say they won't be the last.

Blog by Joey D'Urso

Have a story for us? Email BBC Trending, external

You can follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, and find us on Facebook, external. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.