Renting and sharing: The business of the future

- Published

The younger generation are leading the way and are more willing to share

The earth can only provide for so much stuff before the basic materials needed to make it start to run out.

Many of us hanker after the very latest cars, TVs, computers and the like, but there's a growing realisation that there are not enough raw materials in the world for us all to have them.

Unchecked consumerism, quite simply, is incompatible with a world of finite resources and an exploding global population.

Something has to give, and as supply becomes ever-more constrained, demand must be moderated, at least in the rich industrialised countries that account for the vast majority of global consumption.

There is no one solution to this most complex of issues, but a growing number of businesses are at the forefront of a movement that may go some way to addressing the problem.

Making money

It's a simple concept - instead of buying products, you rent or share them. The obstacles may appear entrenched, not least mankind's seemingly innate obsession with accumulating material possessions.

But the benefits to consumers are clear - you only pay for what you need, when you need it, and you don't have to worry about owning obsolete technology or outdated objects.

The success of some of these start-ups suggests businesses can also flourish under this model. Of course most of these companies were not set up to help tackle the problem of resource depletion, but to make money. And many of them are doing rather well.

Car sharing helps take cars off the road, reducing CO2 emissions and pressure on finite resources

Take Zipcar, the car-sharing service. The number of cars in the world is expected to double by 2030, with grave consequences for both resources and CO2 emissions. What better way, then, to share a car rather than buy one, reducing at a stroke demand for these energy-intensive products?

Zipcar leases cars from major manufacturers, then makes them available to its members, who pay an annual fee and an hourly rate for using the car. Compared with buying a car, maintaining, insuring and taxing it, the average member saves more than £3,000 a year, according to the company. And every car shared takes 20 vehicles off the road, it says.

The company is coy about its profitability, but it must be doing something right - more than 750,000 people have joined up. By 2030, there will 30 million members of similar schemes across the world, according to consultancy Frost & Sullivan. It is this growth potential that persuaded global car hire giant Avis to buy out Zipcar for $500m (£318m) earlier this year.

Next step

This simple business model can be applied to all manner of products, and has been embraced by a number of small companies. Girlmeetsdress.com, fashionhire.co.uk and handbagsfromheaven.co.uk, for example, offer access to designer fashions.

Not only can you wear a different dress every night, but you can wear a top designer you may not otherwise be able to afford. Better still, you're not lumbered with a piece that's outdated

Other companies have taken the concept a step further. Rather than buying products to rent out, they simply allow people to share their own possessions.

Whipcar, for example, effectively allows you to rent someone else's car. You pay a membership fee, find someone in your local area who has put their car on the site, and agree a time for you drive it. Insurance and breakdown cover are included.

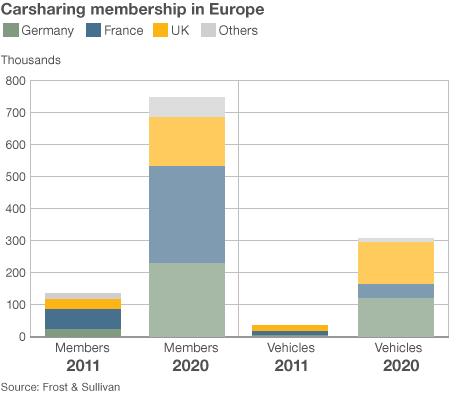

Research by Frost & Sullivan suggests there are 24 similar schemes across Europe, with more than 100,000 members. By 2020, it estimates there will be almost 750,000 people renting each other's cars.

Parkatmyhouse takes the same principle and applies it to parking rather than driving.

But perhaps the most successful company to embrace this business model is Airbnb, which offers users the opportunity to rent rooms or homes in almost 200 countries across the world at a price considerably cheaper than the equivalent hotel. You simply join up, find a place to suit you and get in touch with the property owner.

And by taking a commission on the rent, Airbnb is able to generate serious amounts of cash - one US analyst recently forecast that annual revenues for the company of $1bn were perfectly possible. With very few overheads, that would translate into quite some profit.

The applications of the sharing model are almost endless. Zopa, for example, allows people to borrow money from one another, rather than the bank. The UK-based company has 500,000 members and has facilitated almost £270m in loans. It makes money by charging lenders a flat 1% annual fee on the money they lend. And it's not alone - there are about 35 similar so-called peer-to-peer lending schemes around the world.

There are even businesses that allow you to bypass the need for the services of a professional company altogether. Odesk.com, freelancer.com and guru.com, for example, allow you to hire people to do any job you so wish or, conversely, to pitch for jobs you want to do yourself. Again, the company takes a commission on the rate paid - in the case of Odesk, 10%.

'More attractive'

But it's not just start-ups in the service sector that can benefit from a sharing or rental business model, says David Symons at consultancy WSP.

"As resources become more scarce, keeping ownership [of the resources] and leasing them out keeps costs down, while the rising price of raw materials [and production] makes renting even more attractive," he says.

For these reasons, more companies are looking at the benefits of renting, he says, for example manufacturers of air conditioning units, lifts and various white goods.

"If you're providing a service, then you're aligning your own interests with those of your customers, which makes for a longer-term relationship," says Mr Symons. Not to mention the fact that profit margins in the service industry tend to be higher than those in manufacturing.

This would inevitably lead to a more service orientated economy, but this is no bad thing, says Mr Symons - as consumers spend less on owning goods, they have more money to spend elsewhere.

"It just means money is circulating in services rather than products."

'Magic bullet'

It's early days, but these companies are pioneering a move towards an entirely different way of doing business.

As Rajesh Makwana, director of Share The World's Resources, says: "Even though the business potential of the sharing economy is significant, there are still only relatively small numbers of people participating in this emerging sector".

If the success of Airbnb and Zipcar is anything to go by, this won't be the case for long. Just how long depends somewhat on our willingness to give up what we have for so long been programmed to desire.

The internet and social media have been the catalyst for business models based on renting and sharing

Change is already afoot. "The younger generation are leading the way - they see sharing as a way of life and are not so keen on owning things," says Sarwant Singh at Frost & Sullivan.

Some argue that ownership was never the real issue, but access. The internet and social media has allowed the instant communication needed to put those who want in touch with those who have, and vice versa. Without it, sharing on a grand scale would not be possible.

What is certain is that this new business model is here to stay - the physical limitations of planet Earth demand it.

"It may not be the magic bullet, but it's one way we can use resources more efficiently," says Mr Symons.

So as the global population, and more importantly the middle class, continues to mushroom, we all better get used to the idea of sharing a little more, or at least of owning a little less stuff.

- Published12 June 2012

- Published2 January 2013

- Published15 January 2013