Does India have the will to reform its economy?

- Published

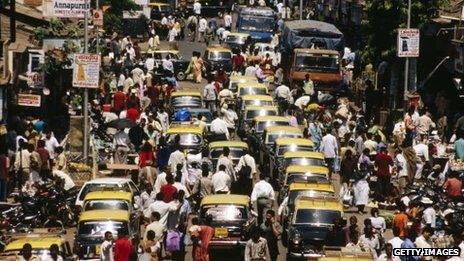

The government faces stiff opposition to some of its proposed economic reforms

India will soon overtake Japan's economic output, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

But is India's formerly booming economy losing steam?

The outlook has been getting gloomier as high growth rates have dropped back, foreign investment has fallen steeply, and 700 million people were left without power earlier this year after the worst blackouts in modern history.

Furthermore, planned reforms and the opening up of the economy often get sidetracked by powerful political and business interests.

Before taking on the role of chief economic adviser to the Indian ministry of finance in August 2012, Professor Raguram Rajan was a chief economist at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), where he was outspoken in his criticism of the Indian government.

In April he said there was "a paralysis of growth-enhancing reforms in India".

Time to act

So, does India have the will to modernise and reform its economy?

"How to jump start the economy is a big issue the government is tackling," Professor Rajan says.

He notes there are a number of projects that have stalled and that public sector firms are sitting on money that could be deployed faster for investments in infrastructure.

He maintains that the government is reacting to complaints of paralysis by getting its fiscal house in order, which had been postponed for a long time partly because there had not been enough political support.

"In September the government bit the bullet and said 'we are going ahead' despite the loss of a coalition partner, and it is important we do it because India's future is at stake," he says.

The new measures include getting spending under control, raising taxes to fund the necessary spending and eventually initiating a broader range of reforms to spread the benefits of growth to more people.

Transparency needed

In his previous post at the IMF, Professor Rajan had spoken about "an unholy alliance between some businessmen and politicians, who together were able to block change."

One deterrent for foreign investors has been what is referred to as the Coalgate scandal: allegations of possible corruption over the allocation of coal deposits to companies and the public sector.

"The scandals about allocation are problematic," he says, adding that "corruption as a whole is problematic".

However, he is adamant that such concerns are being addressed.

"Initially, the reaction can be to crawl into your shell and not do anything, which is part of the reason for the paralysis but, over time, we ask what needs to be done," he says.

He quotes the hugely profitable auction of the 3G mobile phone licenses, which was done with transparency. The process highlighted how little the 2G licenses had been sold for in a less open process.

He points to the public reaction to the lack of transparency.

"One of the good things about India, is when things get bad the democratic process reacts and says 'no no, you can't do this, you have to do better' and that is what we are seeing," he says.

"Going forward, we need much more transparency in government procedures."

He concludes that this will result in more and more natural resources being allocated through transparent auctions.

Foreign investors might also question the state of the country's infrastructure after the power outages, which affected large parts of the country earlier this year.

"People who know India know that the energy supply is an issue which needs to be tackled and one of the biggest problems is the lack of investment," Professor Rajan says.

He maintains that many of the energy companies are not investing because they are overloaded with debt.

Talking about the problems that India faces, he says you can look at the cup as half full or half empty.

"The half-empty version is that these are big problems, the half-full version is that parliament and the public is angry and the government is reacting," he concludes.

- Published18 April 2012

- Published19 September 2012

- Published12 August 2011