Crossrail: Tunnelling beneath London

- Published

A tour through Crossrail's tunnels

In exactly four years' time, Europe's biggest infrastructure project will open to the public.

Crossrail is a new railway line running from east to west across London. It sounds simple enough but this is a project on a scale that echoes the great Brunel himself.

It includes 26 miles of tunnels and we were lucky enough to go down a few, just to see how they are getting on.

I say lucky. You should try climbing down 50 metres of claustrophobic metal staircase in full safety gear and carrying all the camera kit.

The hole we disappeared down will eventually be the new Liverpool Street Crossrail station.

The Fisher Street shaft is seen among the buildings in Holborn

A worker shifts dirt through the eastern ticket hall near Hanover Square

Our guide John, a man who also helped build the Channel Tunnel, took us past all the machines, beeping lorries, cherry pickers and men, away from the lights, down a dark tunnel which eventually just, erm, stops.

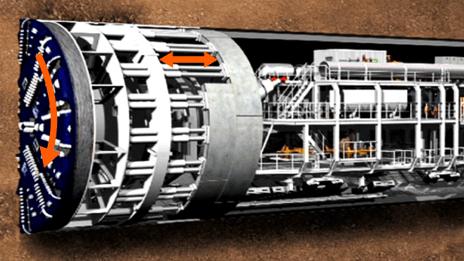

In a few weeks' time, he said, a 1,000-tonne machine will crunch through that wall. I tried to picture it, inching towards us through the clay. Spooky.

Then when it arrives, they'll put it on some rails, drag it to the other end of the site, and it will start gouging out the wall at the other end.

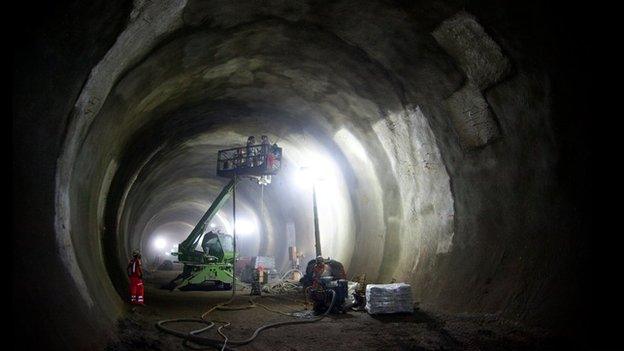

So you can picture it, they've actually used diggers and sprayed concrete mixed with steel fibres (known as Shotcrete) to hollow out most of the stations, and the tunnelling machines connect up all the holes.

The exceptions are Paddington, Canary Wharf and Woolwich stations, which are essentially massive concrete boxes sunk into the ground.

Workers attend to fixings in the partially completed tunnel that will become Bond Street

A total of 26 miles of tunnels are being built beneath the streets of London

There are two big engineering problems they've had to overcome. The first is water pressure. As they dig out the clay, the water in the sand and gravel underneath starts pressing upwards. It's a bit like shaking a Coke bottle with the lid on.

They've had to find a way of relieving that pressure without all the water bursting through. In the same way that you'd open the Coke bottle bit by bit so you don't get soaked, they're relieving the water pressure bit by bit.

When complete, 10 new stations in London are expected to increase the capital's rail capacity by 10%

Secondly, they've had to make sure none of the very heavy, often listed buildings above start moving. There is no danger of anything falling down, we're told, but still, you could get cracks and stresses that you don't want.

The answer to that problem is simple. They push pipes, about the width of drain pipes, into the ground under the buildings. The pipes have little holes all along them. If a building moves (they are all being monitored 24 hours a day) then they squirt grout, about the thickness of a milkshake, through the pipes. It spills out and pushes the ground back up. We're only talking a millimetre or so.

Concrete is spayed (L) on a crossover rail tunnel

Interestingly, they use a similar technique to keep the tower holding Big Ben upright. It sits right over the Jubilee tube line.

In total, eight tunnel-boring machines, each weighing 1,000 tonnes, are inching under the capital. Each contraption is so big that they have a canteen on board for the workers, and they have been named after important women, including the world's first computer programmer, Ada Lovelace, and Phyllis Pearsall, who's credited with inventing London's A to Z.

The machine heading towards the spot we were standing at is called Elizabeth. I'm sure you can work out why.

Crossrail is Europe's biggest infrastructure project

Next March, they're going to bring up around 3,000 skeletons from the graveyard at the old Bethlem (Bedlam) Hospital. The remains will be tested for two years, then reburied in consecrated ground. There had been fears about unearthing anthrax and the plague but they didn't materialise, luckily.

They're also bringing up around 30 Roman skulls.

Two-thirds of the spoil from all that digging is being shipped up to Essex to build Europe's biggest coastal nature reserve.

If you happen to be walking around London in the next four years, try to imagine those 1,000-tonne machines creeping around below your feet, complete with workers having a sarnie in the on-board canteen.

Follow Richard Westcott on Twitter: @BBCwestcott, external

- Published2 November 2014

- Published1 August 2013

- Published27 November 2014

- Published28 October 2014

- Published15 March 2012