China's yuan currency falls for a second day

- Published

Why has China devalued the yuan?

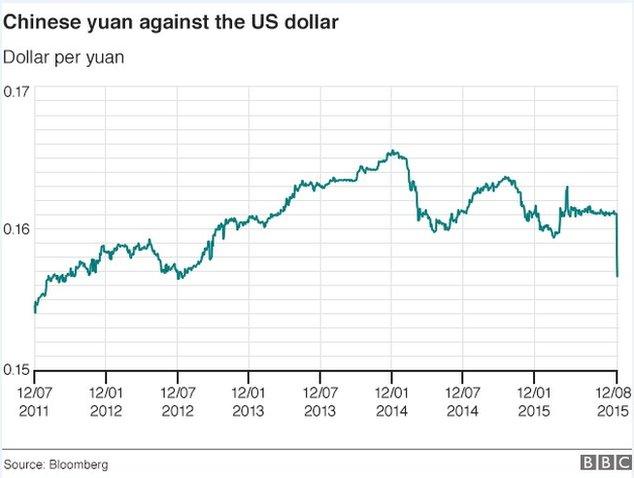

China's Central Bank has again cut the guiding rate for the national currency, the yuan, a day after Tuesday's record 1.9% devaluation.

The move sent fresh shockwaves through Asian markets, but the bank has sought to calm fears, saying it was not the start of a sustained depreciation.

The yuan fell another 1% on Wednesday, marking the biggest two-day lowering of its rate against the dollar in more than two decades.

The new rate is meant to boost exports.

Figures released at the weekend showed Chinese exports fell more than 8% in July, adding to concerns the world's second largest economy is heading for a slowdown.

There were further signs of weakness on Wednesday, when figures showed industrial production in July rose 6% from the previous year. The rise was smaller than expected and was also below the 6.8% increase seen in June.

Fixed asset investment, a measure of state spending on infrastructure, expanded 11.2% for the first half of the year, also below estimates and at its lowest since December 2000.

However, the action on the yuan has sparked fears of a global and destabilising "currency war". There has been criticism from the US, where markets fell sharply overnight.

Read more: Countries' views on effect of yuan devaluation

One-off?

On Wednesday, China's central bank fixed the "official midpoint" for the yuan down 1.6% to 6.3306 against the dollar.

The midpoint is a guiding rate, from which trade can rise or fall 2% during the day.

China has long kept tight control of their currency's value

Until Tuesday, that rate had been determined solely by the People's Bank of China (PBOC) itself. But the rate will now be based on overnight global market developments and how the currency finished the previous trading day.

The bank, which had called Tuesday's 1.9% cut a "one-off" adjustment, sought to reassure financial markets on Wednesday.

"Looking at the international and domestic economic situation, currently there is no basis for a sustained depreciation trend for the yuan," it said in a statement.

Winners and losers

Although the devaluation shocked the international markets, a total move of more than 3% is not significant for most companies. But further falls could start to change the fortunes of some businesses in and out of China. Here are the potential winners and losers:

Winners

Chinese exporters, in particular textile and car companies, could become more competitive.

Foreign retailers will find Chinese consumer goods cheaper, as will companies using Chinese services, products and components.

Foreign tourists to China will get marginal benefits from a cheaper yuan.

Losers

Chinese companies will have to pay more interest on debt in foreign currencies, in particular property companies and local government financing vehicles.

Chinese air carriers are also exposed to foreign currency debt and big fuel bills that have to be paid in dollars.

Exporters to China, particularly of luxury goods, will find it harder to sell as they become more expensive to Chinese consumers.

Backing from IMF

The International Monetary Fund said the move to make the rate more market-based "appears a welcome step".

"Greater exchange rate flexibility is important for China as it strives to give market-forces a decisive role in the economy and is rapidly integrating into global financial markets," the international lender said in a statement.

"We believe that China can, and should, aim to achieve an effectively floating exchange rate system within two to three years."

The IMF added, though, that the decision would not affects its considerations of Beijing's hopes for the yuan to be added to the "special drawing rights" (SDR) reserve currencies.

These are currencies which IMF members can use to make payments between themselves or to the Fund.

China has long been lobbying to have the yuan included alongside the dollar, euro, yen and the British pound.

- Published12 August 2015

- Published12 August 2015

- Published11 August 2015

- Published11 August 2015

- Published11 August 2015

- Published12 August 2015