Can songwriters survive in the age of music streaming?

- Published

Adele's new album, 25, is not available on music streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music

Songwriters have played a crucial part in the success of many global superstars throughout the history of popular music.

Smash hits performed by Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley in the forties or fifties, or Rihanna and Justin Bieber today, were often penned by professionals.

Even internationally-acclaimed singer Adele, whose new album, 25, comes out today, and whose last - 21 - sold more than 30 million copies, co-writes her material.

Not that record labels like to crow about songwriters - most of these hired guns are virtually unknown outside the industry.

But are these powers behind the throne seeing their livelihoods threatened by music videos and digital streaming?

Many fear so.

YouTube threat

What all professional songwriters have in common is a publishing deal, and like the recorded music industry, music publishing is worth billions globally.

But the switch to buying and listening to music in digital rather than physical form has dented revenues, and not just because of piracy - file-sharing that infringes copyright.

Successful songwriters you may not have heard of

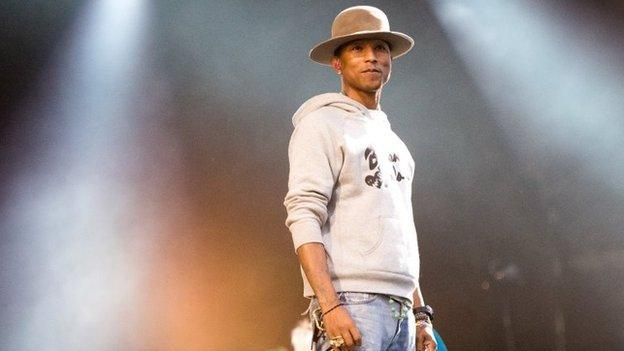

Swedish songwriter and producer Max Martin won his first Grammy award in February

Max Martin: Swedish writer and producer responsible for 21 US number one hits - more than the Beatles - for acts including Taylor Swift (Shake It Off), Katy Perry (Roar) and Britney Spears (...Baby One More Time).

Diane Warren: considered one of the most successful contemporary songwriters, she wrote hits for Aerosmith (I Don't Wanna Miss A Thing) and Toni Braxton (Unbreak My Heart).

Cathy Dennis: Nineties popstar who co-wrote megahits for the likes of Kylie Minogue (Can't Get You Out Of My Head).

Diane Warren with Rita Ora at the Academy Awards in February

Jane Dyball, chief executive of the Music Publishers Association (MPA), says that while streaming is not a bad thing in itself, there are concerns about whether the advertising revenue generated by platforms such as YouTube and Spotify is sufficient to ensure fair returns to writers as well as to artists and record companies.

"Someone suggested they should be called music-supported advertising services rather than advertising-supported music services," Ms Dyball quips.

If a song is streamed a million times, there should be one million payments in return, Ms Dyball says - a concept the industry calls "pay per play".

That is similar to Spotify's business model, but not that of YouTube, which gathers the revenue generated by advertising into a pool and then distributes it to rights holders.

Sia is a successful performer as well as a writer for other artists

The problem is, critics say, YouTube is parsimonious in the extreme.

"It's now time for YouTube to show that it is going to generate revenue back to the industry that reflects the amount of music its users consume," says Ms Dyball.

If you can get music for free via YouTube, why pay for subscription services such as Spotify - which now has 20 million paying users - or Apple Music - which has 6.5 million paying subscribers?

Slim pickings

There is also disquiet about SoundCloud, a German music streaming platform. The industry body PRS for Music - which collects royalties for more than 111,000 songwriters, composers and music publishers - says it lacks a licence to play music in the UK and is taking legal action against Soundcloud for unpaid royalties.

Mark Lawrence, chief executive of the Association for Electronic Music, told Music Business Worldwide, external he hopes it will mean that "one writer and/or one artist getting one play can be confident of earning one payment, however small".

Singer-songwriter Ed Sheeran has enjoyed great success

Robert Ashcroft, chief executive of PRS for Music, says times are good for successful artists who write their own material - like Ed Sheeran - but believes things are more difficult for less well-known writers.

With album sales dwindling in favour of individual song downloads, budding songwriters have to hope their songs are streamed by music fans in the face of competition from the millions already available.

And the royalties earned from streaming can be minuscule.

Kevin Kadish, co-writer of the Meghan Trainor smash hit, All About That Bass, says he earned just $5,679 from 178 million streams of the song. The video has been watched more than 1.1 billion times on YouTube.

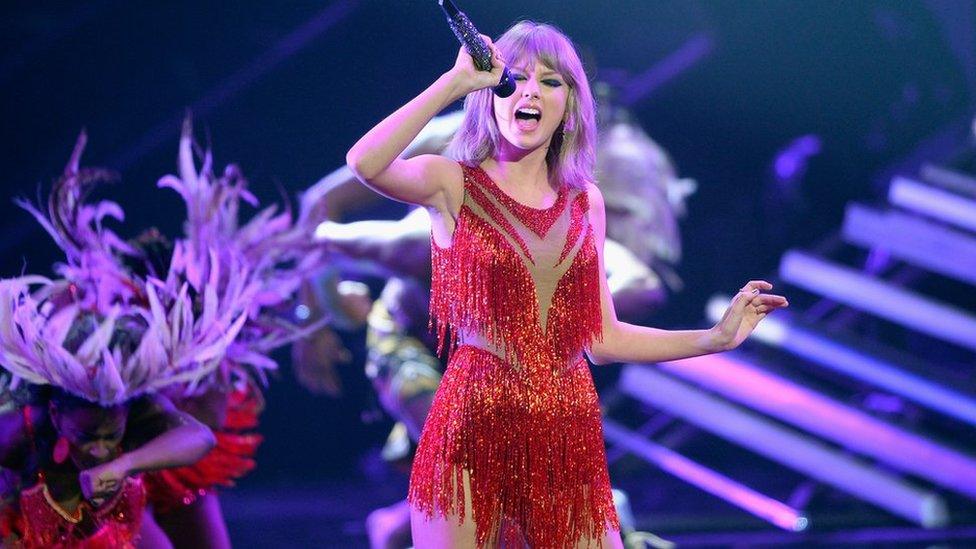

Taylor Swift forced Apple Music to change its music streaming payment policy

Singer Taylor Swift successfully forced Apple Music to reverse policy and pay artists for music streamed during trial periods of its music service, saying it was "unfair to ask anyone to work for nothing".

Mr Ashcroft says that paid-for streaming can be a viable replacement for downloads, but only if the problem of under-licensed - by which he means YouTube - and un-licensed platforms - Soundcloud - can be addressed.

"Spotify is not the problem - the problem is that the legal playing field is not level," he says.

Publishing doldrums

Meanwhile the music publishing business seems to be stalling.

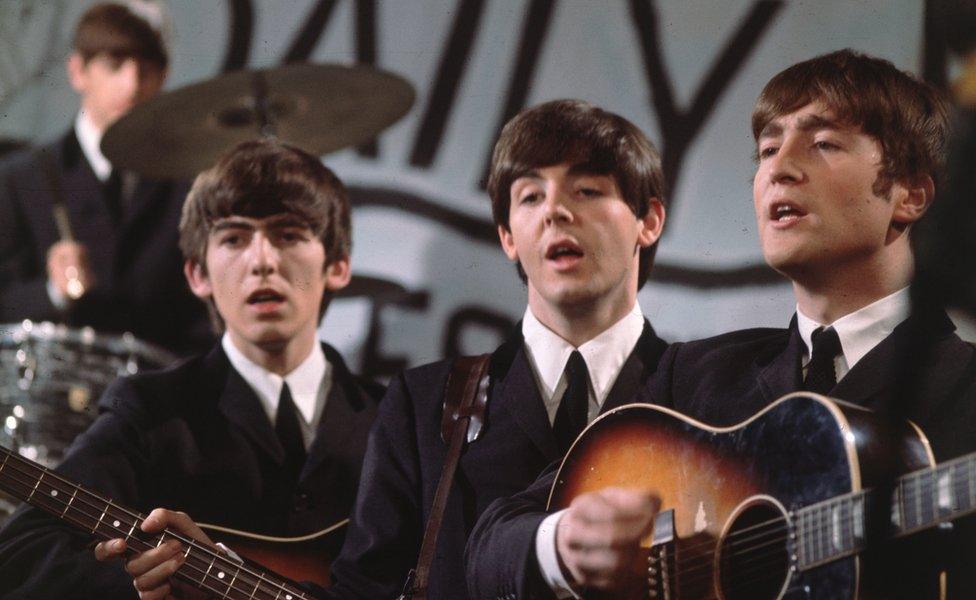

The world's biggest music publisher is Sony/ATV, which also owns the EMI publishing business and the rights to the Beatles' back catalogue, had revenues of about $660m (£435m) in the first half of 2015 - a sum as high as the combined turnover of rivals Universal Music Publishing and Warner/Chappell.

Sony/ATV owns the rights to most of the Beatles' songs

Despite this, Sony, which has co-owned the publishing joint venture with the estate of Michael Jackson since 1995, wants to sell its stake.

In a leaked email, Sony chief financial officer, Kenichiro Yoshida, wrote that the publishing business is complex and "is impacted by the market shift to streaming".

Slow music

Even when songwriters do generate some income from their tunes, they can often wait up to two years for payment, as antiquated systems struggle to cope in the digital age - PRS says the number of individual music plays has risen from 15 million a year five years ago to one trillion.

PRS is now part of a new pan-European licensing system called ICE, external that will more accurately match songwriters, composers and publishers of pieces of music to ensure rights holders get paid more speedily - describing it the biggest revolution in the history of music copyright.

The world of music will always need songwriters, but until the economics of the industry are recalibrated fairly for the digital age, their songs may struggle to be heard.

- Published30 June 2015

- Published15 July 2015

- Published15 April 2015