Is free trade good or bad?

- Published

Trade makes the world go round, but how free can it remain?

Free trade is something of a sacred cow in the economics profession.

Moving towards it, rather slowly, has also been one of the dominant features of the post-World War Two global economy.

Now there are new challenges to that development.

The UK is leaving the European Union and the single market - though in her speech this week, British Prime Minister Theresa May promised to push for the "freest possible trade" with European countries and to sign new deals with others around the world.

Most obviously Donald Trump has raised the possibility of quitting various trade agreements, notably Nafta, the North American Free Trade Agreement with Mexico and Canada. Even the World Trade Organization (WTO) has proposed new barriers to imports.

In Europe, trade negotiations with the United States and Canada have run into difficulty, reflecting public concerns about the impact on jobs, the environment and consumer protection.

The WTO's Doha Round of global trade liberalisation talks has run aground.

The World Trade Organization is based in Geneva and came into being in 1995

The case for trade without government imposed barriers has a long history in economics.

Comparative advantage

Adam Smith, the 18th Century Scottish economist who many see as the founding father of the subject, was in favour of it. But it was a later British writer, David Ricardo in the 19th Century, who set out the idea known as comparative advantage, external that underpins much of the argument for freer trade.

It is not about countries being able to produce more cheaply or efficiently than others. You can have a comparative advantage in making something even if you are less efficient than your trade partner.

When a country shifts resources to produce more of one good there is what economists call an "opportunity cost" in terms of how much less of something else you can make. You have a comparative advantage in making a product if the cost in that sense is less than it is in another country.

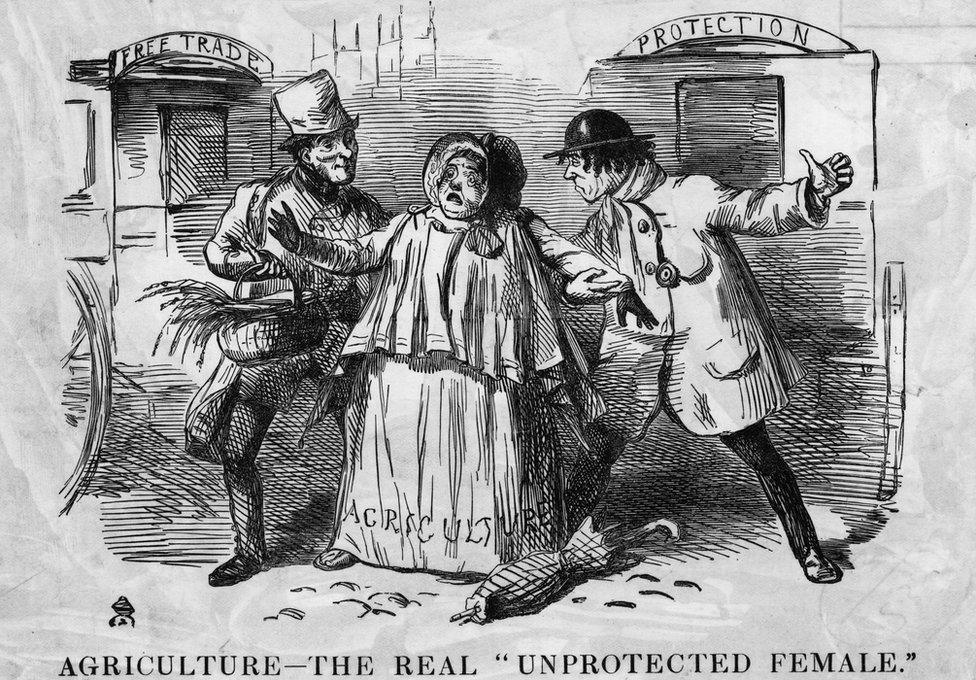

Economic arguments over free trade date back to the 19th Century

If two countries trade on this basis, concentrating on goods where they have a comparative advantage they can both end up better off.

Another reason that economists tend to look askance at trade restrictions comes from an analysis of the impact if governments do put up barriers - in particular tariffs or taxes - on imports.

There are gains of course. The firms and workers who are protected can sell more of their goods in the home market. But consumers lose out by paying a higher price - and consumers in this case can mean businesses, if they buy the protected goods as components or raw materials.

Avoiding protectionism

The textbook analysis says that those losses add up to more than the total gains. So you get the textbook conclusion that it's best to avoid protection.

Many lower-skilled workers in developed economies feel they have lost out in the drive to globalisation

And this conclusion is regardless of what other countries do. The 19th Century French economist Frederic Bastiat set it out it like this:

"It makes no more sense to be protectionist because other countries have tariffs than it would to block up our harbours because other countries have rocky coasts."

The implication is that unilateral trade liberalisation makes perfect sense.

A more recent theory of what drives international trade looks at what are called economies of scale - where the more a firm produces of some good, the lower cost of each unit.

The associated specialisation can make it beneficial for economies that are otherwise very similar to trade with one another. This area is known as new trade theory and the Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman, external was an important figure in developing it.

Post-war trade

The basic idea that it's good to have freer trade has underpinned decades of international co-operation on trade policy since World War Two.

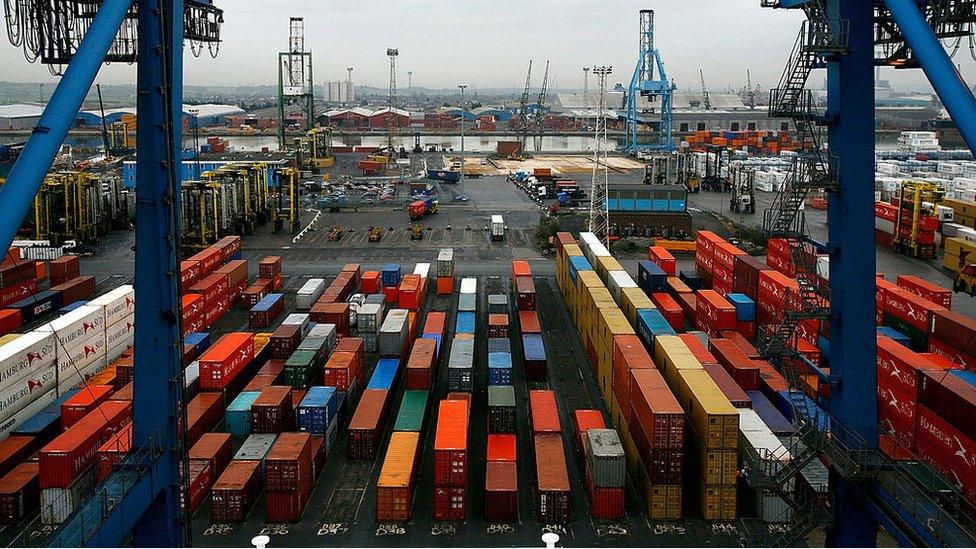

Free trade has been a cornerstone of the post-war world

The period since 1945 has been characterised by a gradual lowering of trade barriers. It happened in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, which began life in 1948 as a forum for governments to negotiate lower tariffs.

Its membership was initially small, but by the time it was replaced by the World Trade Organization in 1995, most countries had signed up.

The motivation was to end or reduce the protectionism or barriers to trade that went up in the 1930s. It is not generally thought that those barriers caused the Great Depression, but many do think they aggravated and prolonged it., external

The process of post-war trade liberalisation, external was driven largely by a desire for reciprocal concessions - better access to others' markets in return for opening your own.

But what is the case against free (or at least freer) trade?

First and foremost is the argument that it creates losers as well as winners.

What Ricardo's theory suggested was that all countries engaging in trade could be better off. But his idea could not address the question of whether trade could create losers as well as winners within countries.

Economic theory says if governments adopt protectionism, total losses will outweigh total gains

Work by two Swedish Nobel Prize winners, Eli Hecksher and Bertil Ohlin, subsequently built on by the American Paul Samuelson developed the basic idea of comparative advantage in a way that showed that trade could lead to some groups losing out, external.

Putting it very briefly, if a country has a relatively abundant supply of, for example, low-skilled labour, those workers will gain while their low-skilled counterparts in countries where it is less abundant will lose.

There has been a debate about whether this approach fits the facts, but some do see it as a useful explanation of how American industrial workers (for example) have been adversely affected by the rise of competition from countries such as China.

A group of economists including David Autor, external of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology looked at the impact on areas where local industry was exposed to what they call the China shock.

"Adjustment in local labour markets is remarkably slow, with wages and labour-force participation rates remaining depressed and unemployment rates remaining elevated for at least a full decade after the China trade shock commences.

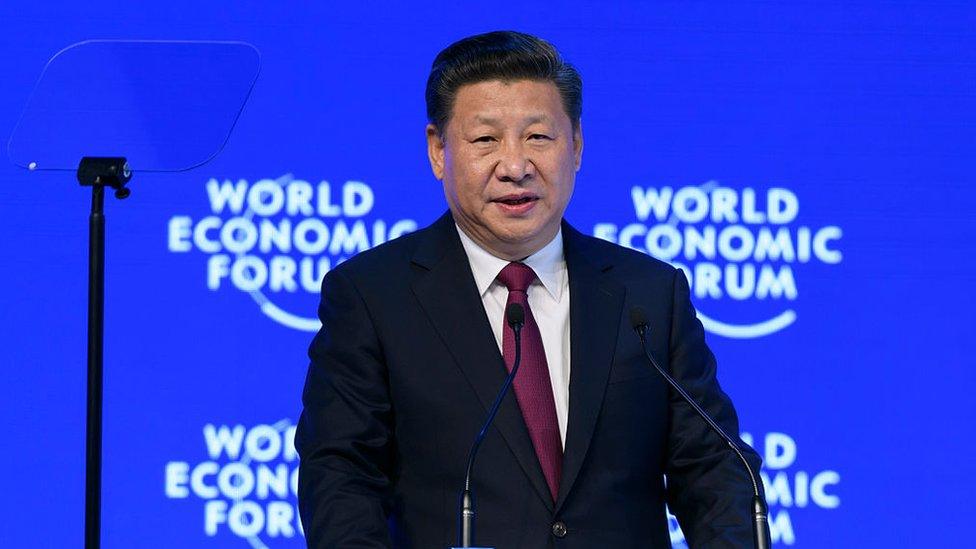

At this week's World Economic Forum, Chinese President Xi Jinping warned against isolationist moves that could spark a trade war

"Exposed workers experience greater job churning and reduced lifetime income."

Compensating losers

Still if you accept that overall countries gain, then the winners could in principle fully compensate the losers and still be better off.

Such programmes do exist. Countries that have unemployment benefits provide assistance to people who have lost their jobs. Some of those people will have been affected by competition from abroad.

The United States has a programme that is specially targeted for people who lose their jobs as a result of imports, called Trade Adjustment Assistance.

But is it enough? Lawrence Mishel, external of the Economic Policy Institute, a think-tank in Washington writes: "The winners have never tried to fully compensate the losers, so let's stop claiming that trade benefits us all."

Which arguments will Donald Trump be listening to in the White House?

In any case, it is not clear that compensation would do the trick. As Mark Carney,, external the Bank of England governor noted, they may lose their jobs and also "the dignity of work".

He is keen on maintaining open markets for trade, but recognises the need to do something about what you might call the side effects.

To return to recent political developments - Donald Trump clearly did get support from many of those people in areas of the US where industry has declined.

We don't yet know how he will address those issues when he takes his place in the White House.

Perhaps his threats to introduce new tariffs are just that - threats. But the post-war trend towards more liberalised international trade looks more uncertain than it has for many years.

- Published9 January 2017

- Published4 January 2017

- Published3 January 2017