Geeks v government: The battle over public key cryptography

- Published

Two graduate students stood silently beside a lectern, listening as their professor presented their work to a conference.

Usually, the students would want the glory. And they had, just a couple of days previously. But their families talked them out of it.

A few weeks earlier, the Stanford researchers had received an unsettling letter from a shadowy US government agency. If they publicly discussed their findings, the letter said, it would be deemed legally equivalent to exporting nuclear arms to a hostile foreign power.

Stanford's lawyer said he thought they could defend any case by citing the First Amendment's protection of free speech. But the university could cover legal costs only for professors. So the students were persuaded to keep schtum.

What was this information that US spooks considered so dangerous? Were the students proposing to read out the genetic code of smallpox or lift the lid on some shocking presidential conspiracy?

No: they were planning to give the International Symposium on Information Theory an update on their work on public key cryptography.

Find out more

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations which have helped create the economic world we live in.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

The year was 1977. If the government agency had managed to silence academic cryptographers, they might have prevented the internet as we know it.

To be fair, that wasn't their plan. The World Wide Web was years away. And the agency's head, Adm Bobby Ray Inman, was genuinely puzzled about the academics' motives.

He felt cryptography - the study of sending secret messages - was of practical use only to spies and criminals.

Three decades earlier, other brilliant academics had helped win the war by breaking the Enigma code, enabling the Allies to read secret Nazi communications.

Complicated maths

Now Stanford researchers were freely disseminating information that might help adversaries in future wars to encode their messages in ways the US couldn't crack.

His concern was reasonable. Throughout history, the development of cryptography has been driven by conflict.

Two thousand years ago, Julius Caesar sent encrypted messages to far-flung outposts of the Roman empire - he'd arrange in advance that recipients would simply shift the alphabet by some predetermined number.

For example, "jowbef Csjubjo" - if you substitute each letter with the preceding one - reads "invade Britain".

Deciphering the Enigma code gave a significant strategic boost to the Allied campaign in WW2

That kind of thing wouldn't have taken the Enigma codebreakers long to crack. Today, encryption is typically numerical: first, convert the letters into numbers and then perform some complicated mathematics on them.

The recipient needs to know how to unscramble the message by performing the same mathematics in reverse. That's known as symmetrical encryption. It's like securing a message with a padlock, having already provided a key.

The Stanford researchers wondered whether encryption could be asymmetrical. Could you send an encrypted message to a stranger you'd never met before which only they could decode?

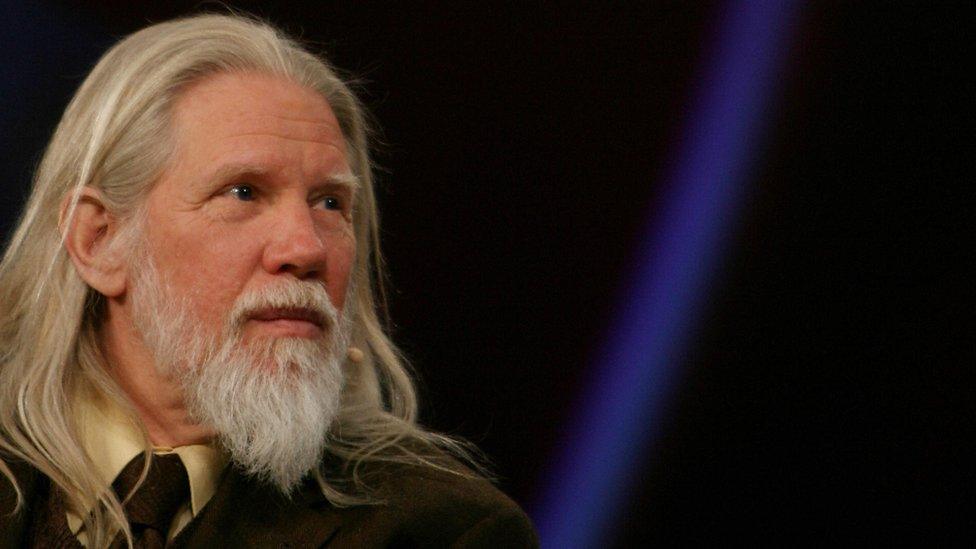

Before 1976 most experts would have said it was impossible. Then Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman published a breakthrough paper. It was Hellman who, a year later, would defy the threat of prosecution by presenting his students' work.

That same year, three researchers at MIT - Ronald Rivest, Adi Shamir and Leonard Adleman - turned the Diffie-Hellman theory into a practical technique, called RSA encryption, after their surnames.

A public key for private messages

These academics had realised that some mathematics are a lot easier to perform in one direction than another.

Take a very large prime number - one that's not divisible by anything other than itself. Then take another. Multiply them together. That gives you an extremely large "semi-prime" number, one divisible only by two prime numbers.

It turns out it's exceptionally hard for someone else to take that semi-prime number and figure out which two prime numbers were multiplied together to produce it.

Whitfield Diffie's work marked a paradigmatic shift in cryptography

Public key cryptography works by exploiting this difference.

In effect, an individual publishes his semi-prime number - his public key - for anyone to see. And the RSA algorithm allows others to encrypt messages with that number, in such a way that they can be decrypted only by someone who knows the two prime numbers that produced it.

It's as if you're distributing open padlocks for the use of anyone who wants to send you a message which only you can unlock. They don't need to have your private key to protect the message and send it to you.

They just need to snap shut one of your padlocks around it.

Security and authenticity

In theory, it's possible for someone else to pick your padlock by figuring out the right combination of prime numbers. But it takes unfeasible amounts of computing power.

In the early 2000s, RSA Laboratories published some semi-primes and offered cash prizes to anyone who could figure out the primes that produced them.

Someone did scoop a $20,000 (£16,000) reward - but only after 80 computers worked on the number non-stop for five months. Larger prizes for longer numbers went unclaimed.

No wonder Adm Inman fretted about this knowledge reaching America's enemies.

More from Tim Harford:

But Prof Hellman had understood something the spy chief had not.

The world was changing and electronic communication was becoming more important. Many private sector transactions would be impossible without secure communication.

You take advantage of this every time you send a confidential work email, or buy something online, or use a banking app, or visit any website that starts with "https".

Without public key cryptography, anyone would be able to read your messages, see your passwords and copy your credit card details.

Public key cryptography also enables websites to prove their authenticity - without it, there'd be many more phishing scams. The internet would be a very different place and far less economically useful.

To his credit, the spy chief soon accepted that the professor had a point and no prosecutions followed. Indeed, the two developed an unlikely friendship.

The quantum threat

But Adm Inman was right that public key cryptography would complicate his job.

Encryption is just as useful to drug dealers, child pornographers and terrorists as it is to you and me paying for something on eBay.

From a government perspective, perhaps the ideal situation would be if encryption can't be easily cracked by ordinary folk or criminals - thereby securing the internet's economic advantages - but government can still see everything that's going on.

Edward Snowden leaked tens of thousands of documents revealing mass surveillance by the US and UK governments

The agency Adm Inman headed was called the National Security Agency (NSA). In 2013, Edward Snowden released secret documents showing just how the NSA was pursuing that goal.

The debate Snowden started rumbles on. If we can't restrict encryption only to the good guys, what powers should the state have to snoop - and with what safeguards?

Meanwhile, another technology threatens to make public key cryptography altogether useless: quantum computing.

By exploiting the strange ways in which matter behaves at a quantum level, quantum computers could potentially perform some calculations significantly more quickly than regular computers.

One of those calculations is taking a large semi-prime number and figuring out which two prime numbers you'd have to multiply to get it. If that becomes easy, the internet becomes an open book.

Quantum computing is still in its early days.

But 40 years after Diffie and Hellman laid the groundwork for internet security, academic cryptographers are now racing to maintain it.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published4 April 2017

- Published27 March 2017

- Published27 March 2017

- Published22 January 2016

- Published2 March 2016

- Published2 March 2016