Superstar economics: How the gramophone changed everything

- Published

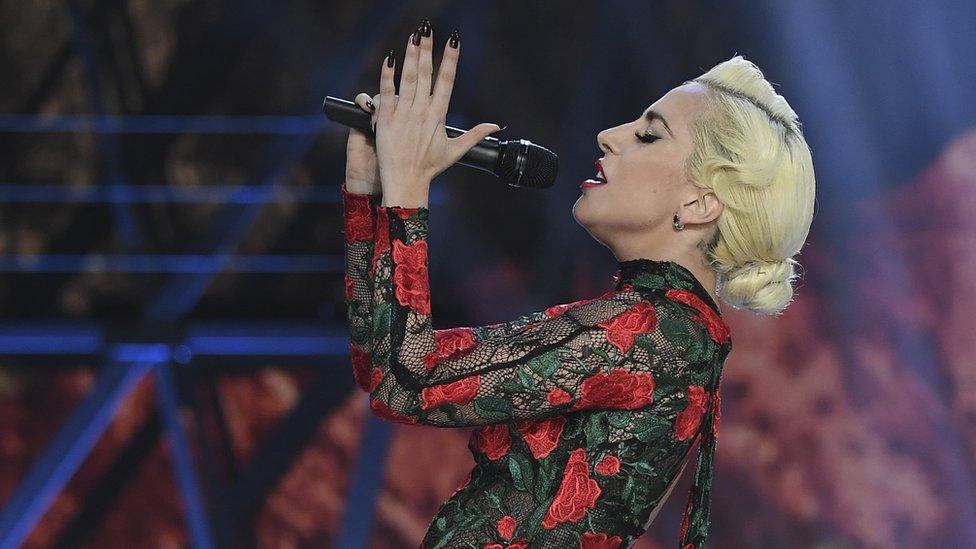

Who is the best paid solo singer in the world? In 2015, according to Forbes, external, it was probably Elton John, who reportedly made $100m (£79m).

U2 apparently made twice as much as that, but there are four of them. There's only one Elton John.

If we'd asked that question 215 years ago, the answer would have been Mrs Elizabeth Billington, to some the greatest English soprano who ever lived.

Sir Joshua Reynolds once painted Mrs Billington holding a book of music, listening to a choir of angels. The composer Joseph Haydn thought the portrait an injustice: the angels, said Haydn, should have been listening to her.

Elizabeth Billington was something of a sensation offstage too.

A scurrilous biography of her sold out in less than a day.

It contained what were purportedly copies of intimate letters about her famous lovers - including, they say, the Prince of Wales.

Such was her fame, she attracted a bidding war for her performances.

The managers of London's leading opera houses at the time - Covent Garden and Drury Lane - fought so desperately for her that she ended up singing at both venues, alternating between the two, pulling in at least £10,000 in the 1801 season.

It was a remarkable sum.

But in today's terms, it's a mere £687,000, or about $1m - just 1% of Elton John's earnings.

So why is Elton John worth 100 Elizabeth Billingtons?

Find out more

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Almost 60 years after Elizabeth Billington's death, the great economist Alfred Marshall analysed the impact of the electric telegraph, which then connected America, Britain, India, and Australia.

Thanks to such modern communications, he wrote: "Men who have once attained a commanding position are enabled to apply their constructive or speculative genius to undertakings vaster, and extending over a wide area, than ever before."

The world's top industrialists were getting richer, faster.

The gap between themselves and less outstanding entrepreneurs was growing.

But not every profession's best and brightest could gain in the same way, Marshall said.

Take the performing arts. "[The] number of persons who can be reached by a human voice," he wrote, "is strictly limited." And so, in consequence, was vocalists' earning power.

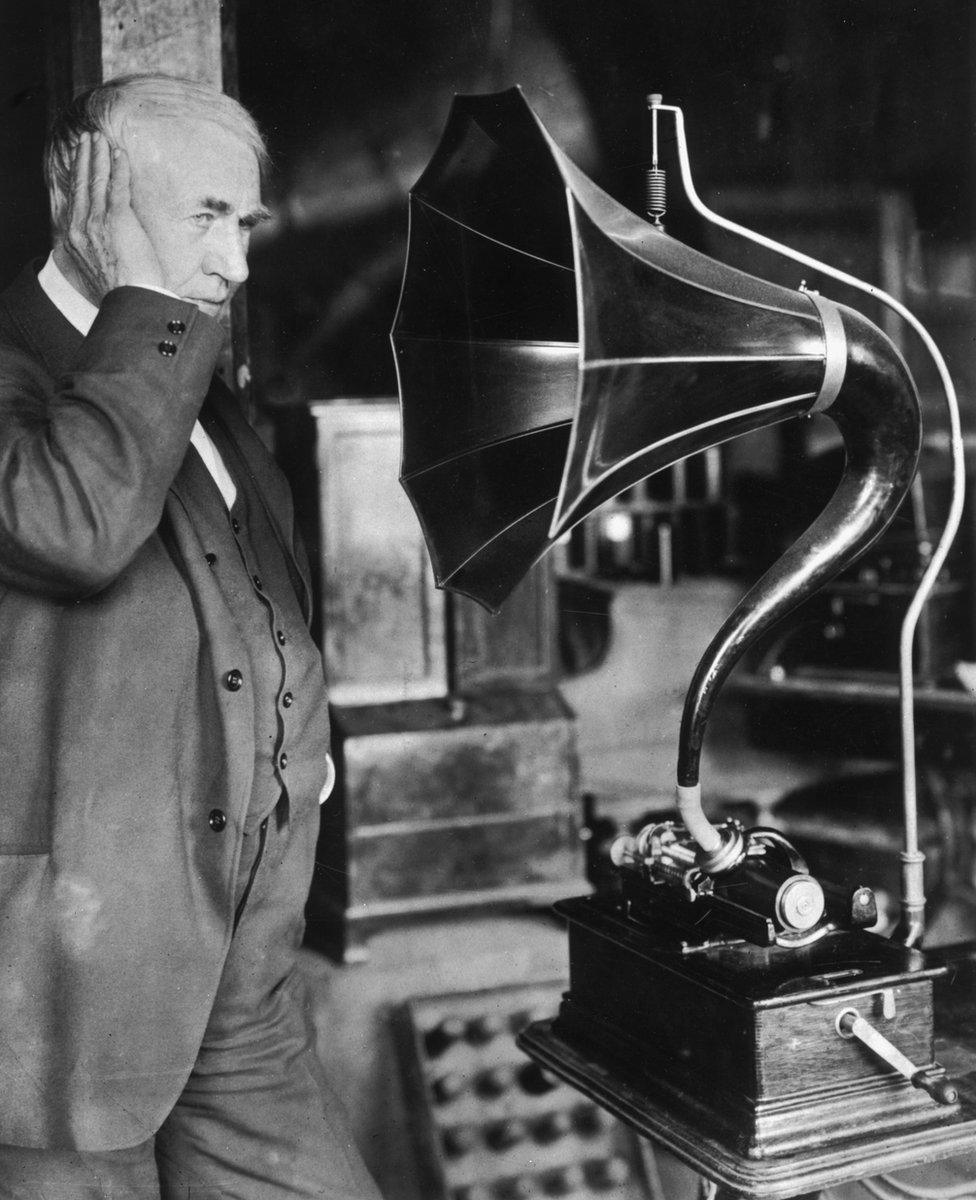

But just two years later, in 1877, Thomas Edison applied for a patent for his phonograph, the first machine that could both record and reproduce the human voice.

Nobody seemed quite sure what to do with the technology at first.

The French publisher Edouard-Leon Scott de Martinville had already developed the phonoautograph, a device intended to provide a visual record of the sound of a human voice - a little like a seismograph records an earthquake.

But it doesn't seem to have occurred to Martinville that one might try to convert the recording back into sound again.

Soon enough, the application of the new technology became clear: you could record the best singers in the world, and sell the recordings.

At first, making a recording was a bit like making carbon copies on a typewriter: a single performance could be captured on only three or four phonographs at once.

In the 1890s, there was great demand to hear a song by the American singer George W Johnson.

He reportedly spent day after day singing the same song till his voice gave out - but even singing it 50 times a day churned out a mere 200 records.

'Superstar' economics

When Emile Berliner introduced recordings on a disc, rather than Edison's cylinder, it opened the way to mass-production.

Then came radio and film.

Performers such as Charlie Chaplin could reach a global market just as easily as the men of industry described by Alfred Marshall.

For the Charlie Chaplins and Elton Johns of the world, new technologies meant wider fame and more money.

But for the journeymen singers, it was a disaster.

In Elizabeth Billington's day, many half-decent singers made a living performing in music halls.

After all, Billington herself could sing in only one hall at a time.

But when you can listen to the best performers in the world at home, why pay to hear a merely competent act in person?

Thomas Edison's phonograph led the way towards a winner-take-all dynamic in the performing industry.

The top performers went from earning like Mrs Billington to earning like Elton John.

But the only-slightly-less good went from making a comfortable living to struggling to pay their bills: small gaps in quality became vast gaps in income.

In 1981, an economist called Sherwin Rosen called this phenomenon "the superstar economy".

Imagine, he said, the fortune that Mrs Billington might have made if there had been phonographs in 1801.

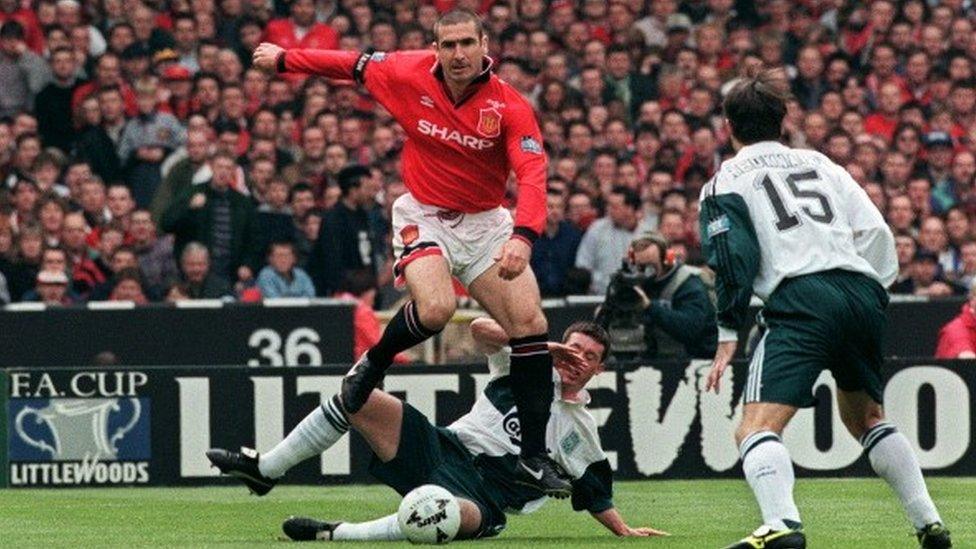

Satellite television has massively boosted the average wages of Premier League players versus those in the lower divisions

Technological innovations have created superstar economics in other sectors, too.

Satellite television has been to footballers what the gramophone was to musicians, or the telegraph to 19th Century industrialists.

If you were the world's best footballer a few decades ago, no more than a stadium-full of fans could have seen you play every week.

Now, your every move can be watched by hundreds of millions on every continent.

And as the market for football expanded, so has the gap in pay between the very best and the merely very good.

More from Tim Harford

As recently in the 1980s, footballers in English football's top tier used to earn twice as much as those in the third tier, playing for - say - the 50th best team in the country.

Now, average wages in the Premier League are 25 times those earned by the players two divisions down.

Technological shifts can dramatically change who gets what, and they are wrenching because they can be so abrupt - and because the people concerned have the same skills as before, but suddenly have very different earning power.

'Unique situation'

Throughout the 20th Century, new innovations - the cassette, the CD, the DVD - maintained the economic model created by the gramophone.

But at the end of the century came the MP3 format, and fast internet connections.

Suddenly, you didn't have to spend £10 on a plastic disc to hear your favourite music - you could find it online, free.

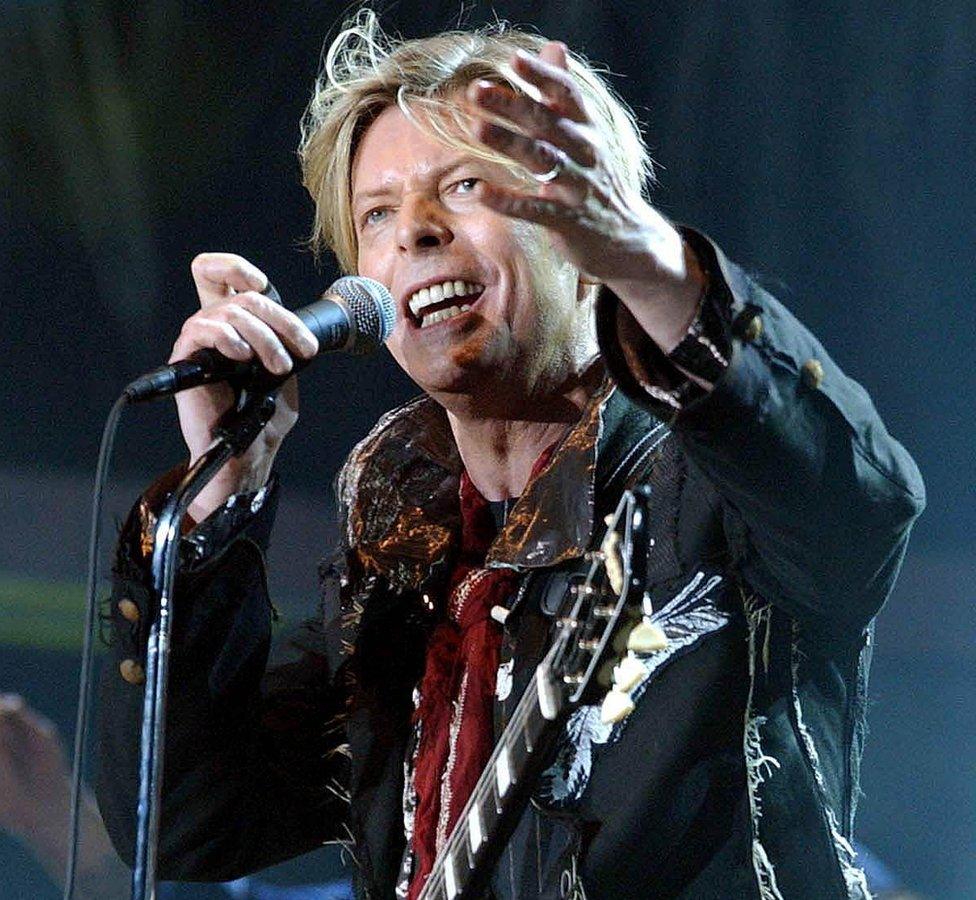

David Bowie recognised the seismic effect digital technology would have on the music industry

In 2002, David Bowie warned his fellow musicians that they were facing a very different future.

"Music itself is going to become like running water or electricity," he said.

"You'd better be prepared for doing a lot of touring because that's really the only unique situation that's going to be left."

Bowie seems to have been right.

Artists have stopped using concert tickets as a way to sell albums, and started using albums as a way to sell concert tickets.

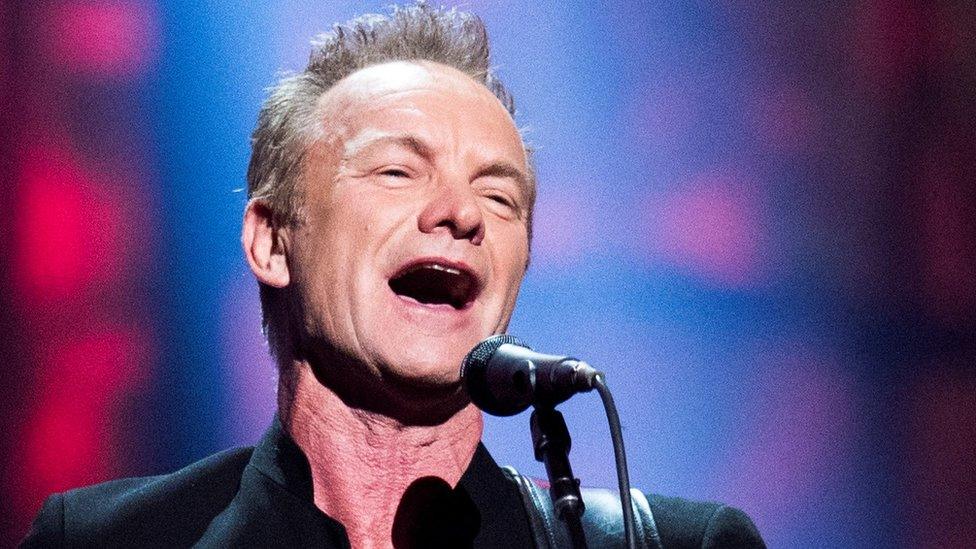

But we haven't returned to the days of Mrs Billington.

Amplification, stadium rock, global tours and endorsement deals mean that the most admired musicians can still profit from a vast audience.

Inequality remains alive and well - the top 1% of artists take more than five times more money from concerts than the bottom 95% put together.

The gramophone may be passe, but the ability of technological progress to change who wins - and who loses - persists.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published13 April 2017

- Published12 February 2017

- Published26 January 2017

- Published4 January 2017

- Published7 December 2016

- Published7 December 2016

- Published7 September 2015