Is this the most influential work in the history of capitalism?

- Published

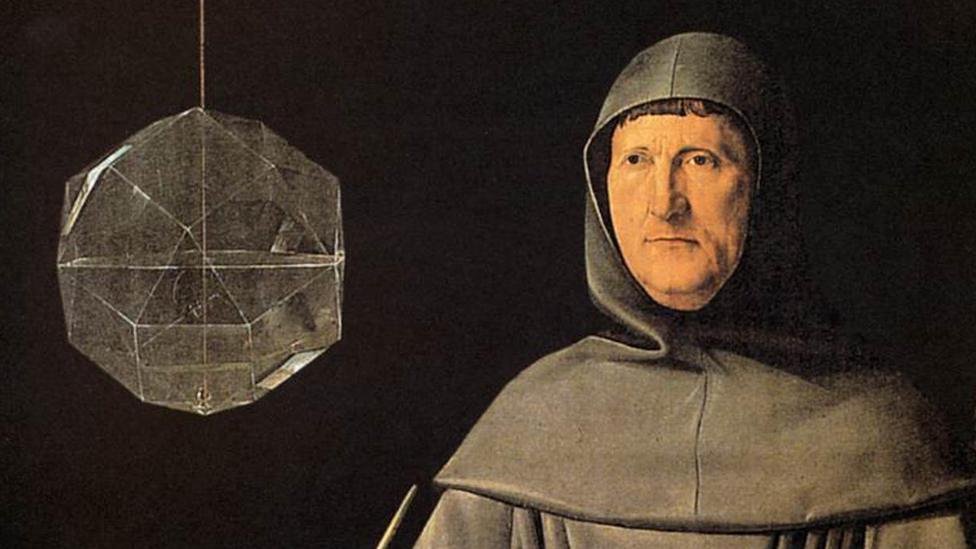

Renaissance mathematician Luca Pacioli is seen as the father of double-entry bookkeeping

In 1495 or thereabouts, Leonardo da Vinci himself, the genius's genius, noted down a list of things to do in one of his famous notebooks.

These to-do lists, written in mirror-writing and interspersed with sketches, are magnificent.

"Find a master of hydraulics and get him to tell you how to repair a lock, canal and mill in the Lombard manner." "Draw Milan." "Learn multiplication from the root from Maestro Luca."

Leonardo was a big fan of Maestro Luca, better known today as Luca Pacioli.

Pacioli was, appropriately enough, a Renaissance Man: - educated for a life in commerce, but also a conjuror, a chess master, a lover of puzzles, a Franciscan Friar, and a professor of mathematics.

Today he is celebrated as the most famous accountant who ever lived.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations which have helped create the economic world in which we live.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Pacioli is often called the father of double-entry bookkeeping, but he didn't invent it.

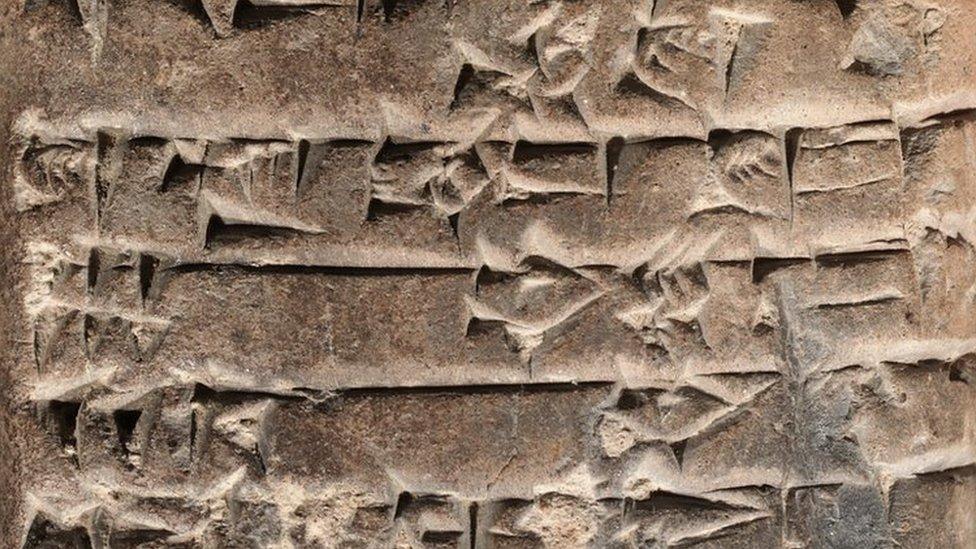

The double-entry system - known in its day as "bookkeeping alla Veneziana," or "in the Venetian style" - was being used two centuries earlier, around 1300.

The Venetians had abandoned as impractical the Roman system of writing numbers, and were instead embracing Arabic numerals.

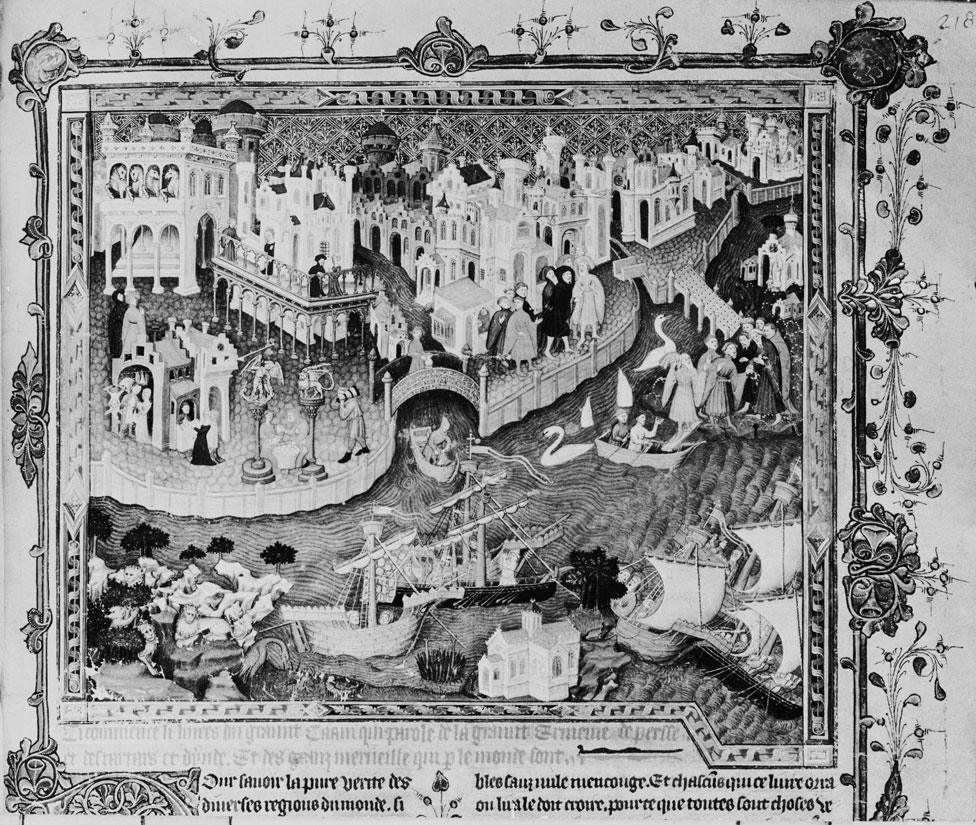

Venice in the 1300s - when Marco Polo set off on his famous travels to the Far East - was already a sophisticated crossroads of trade and ideas

They may have also taken the idea of double-entry book keeping from the Islamic world, or even from India, where there are tantalising hints that double-entry bookkeeping techniques date back thousands of years.

Or it may have been a local Venetian invention, repurposing the new Arabic mathematics for commercial ends.

Intricate transactions

Before the Venetian style caught on, accounts were rather basic. Early medieval merchants were little more than travelling salesmen. They had no need to keep accounts - they could simply check whether their purse was full or empty.

But as the commercial enterprises of the Italian city states grew larger, and became more dependent on financial instruments such as loans and currency trades, the need for a more careful reckoning became painfully clear.

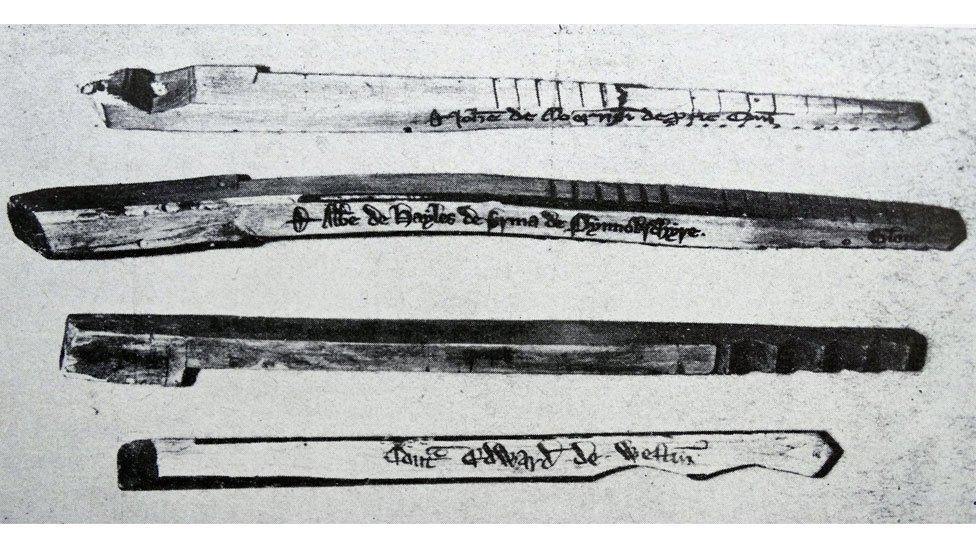

We have a remarkable record of the business affairs of Francesco di Marco Datini, a merchant from Prato, near Florence, who kept accounts for nearly half a century, from 1366 to 1410.

They begin as little more than a financial diary, but as his business grew more complex, he needed something more sophisticated.

We can see how Datini tracked his increasingly intricate financial transactions

Late in 1394, Datini orders wool from Mallorca.

Six months later the sheep are shorn. Several months after that, 29 sacks of wool arrive in Pisa, via Barcelona. The wool is coiled into 39 bales. Of these, 21 go to a customer in Florence and 18 go to Datini's warehouse, arriving in 1396, over a year after the initial order. They are then processed by more than 100 separate subcontractors.

Eventually, six long cloths go back to Mallorca via Venice, but don't sell, so are hawked in Valencia and North Africa instead. The last cloth is sold in 1398, nearly four years after Datini's original order.

Fortunately, he had been using bookkeeping alla Veneziana for more than a decade, so was able to keep track of this extraordinarily intricate web of transactions.

Enormous influence

So what, a century later, did the much lauded Luca Pacioli add to the discipline of bookkeeping? Quite simply, in 1494, he wrote the book.

"Summa de Arithmetica, Geometria, Proportioni et Proportionalita" was an enormous survey of everything that was known about mathematics - 615 large and densely typeset pages.

Amidst this colossal textbook, Pacioli included 27 pages that are regarded by many as the most influential work in the history of capitalism. It was the first description of double-entry bookkeeping to be set out clearly, in detail and with plenty of examples.

Pacioli's book was sped on its way by a new technology: half a century after Gutenberg developed the movable type printing press, Venice was a centre of the printing industry.

Symmetry and balance

His book enjoyed a long print run of 2,000 copies, and was widely translated, copied, and plagiarised across Europe.

Double-entry bookkeeping was slow to catch on, perhaps because it was technically demanding and unnecessary for simple businesses. But after Pacioli it was always regarded as the pinnacle of the art.

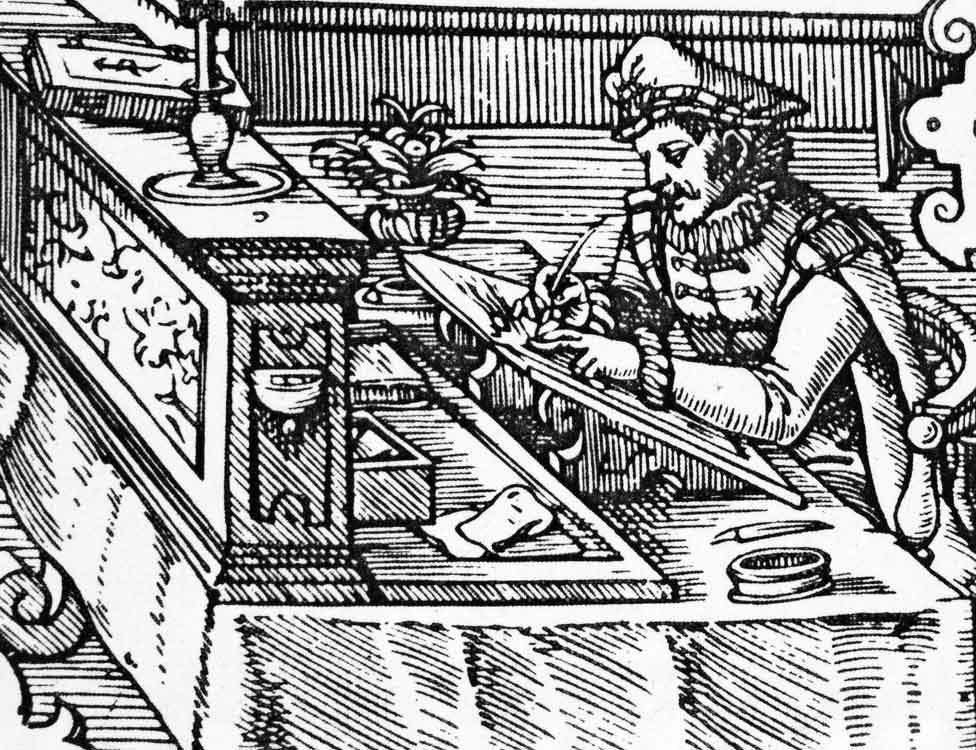

This 1585 woodcut shows a German merchant's accountant doing double-entry bookkeeping

As the industrial revolution unfolded, the ideas that Pacioli had set out came to be seen as fundamental to business life. The system used across the world today is essentially the one that Pacioli described.

Pacioli's system has two key elements.

First, he describes a method for taking an inventory, and then keeping on top of day-to-day transactions using two books - a rough memorandum and a tidier, more organised journal. Then he uses a third book - the ledger - as the foundation of the system, the double-entries themselves.

Every transaction was recorded twice in the ledger. If you sell cloth for a ducat, you must account for both the cloth and the ducat.

The double-entry system helps to catch errors, because every entry should be balanced by a counterpart, a divine-like symmetry which appealed to a Renaissance Man.

Practical tool

It was during the industrial revolution that double-entry bookkeeping became seen not just as an exercise for mathematical perfectionists, but as a tool to guide practical business decisions.

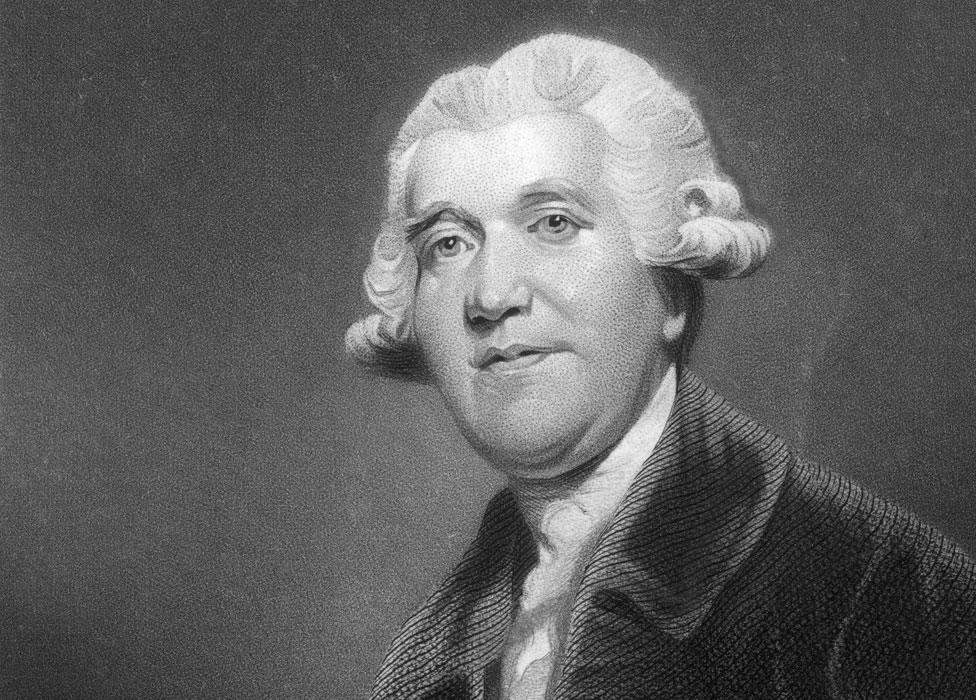

One of the first to see this was Josiah Wedgwood, the pottery entrepreneur. At first, Wedgwood, flush with success and fat margins, didn't bother with detailed accounts.

Josiah Wedgwood used the insight gleaned from detailed accounts to weather a severe recession

But in 1772, Europe faced a severe recession and demand for Wedgwood's ornate crockery collapsed. His warehouses began to fill with unsold stock and workers stood idle.

Wedgwood turned to double-entry bookkeeping to understand where in his business the profits were, and how to expand them.

He realised how much each piece of work was costing him - a deceptively simple-sounding question - and calculated that he should actually expand production and cut prices to boost business.

Others followed, and the discipline of "management accounting" was born - an ever-growing system of metrics and benchmarks and targets, that has led us inexorably to the modern world.

More from Tim Harford:

But in that modern world, accounting does have another role.

It's about ensuring that shareholders in a business receive a fair share of corporate profits - when only the accountants can say what those profits really are.

Here the track record is not encouraging.

Enron's collapse in 2001 was the biggest in US corporate history

A string of 21st century scandals - Enron, Worldcom, Parmalat, and the financial crisis of 2008 - have shown us that audited accounts do not completely protect investors.

A business may, through fraud or mismanagement, be on the verge of collapse. Yet we cannot guarantee that the accounts will warn us of this.

Complacency

Accounting fraud is not a new game. The first companies to require major capital investment were the British railways of the 1830s and 1840s, which needed vast upfront investment before they could earn anything from customers.

Investors poured in, and when railway magnates could not pay the dividends that the investors expected, they simply faked their accounts. The entire railway bubble had collapsed in ignominy by 1850.

Perhaps the railway investors should have read up on their Geoffrey Chaucer, writing around the same time as Francesco Datini, the merchant of Prato.

Accountancy did not protect Chaucer's Shipman character from an audacious con

In Chaucer's Shipman's Tale, a rich merchant is too tied up with his accounts to notice his wife being wooed by a clergyman.

Nor do those accounts rescue him from an audacious con.

The clergyman borrows the merchant's money, gives it to the merchant's wife - buying his way into her bed with her own husband's cash - and then tells the merchant he's repaid the debt, and to ask his wife where the money is.

Accountancy is a powerful financial technology - but it does not protect us from outright fraud, and it may well lure us into complacency. As the neglected wife tells her rich husband, his nose buried in his accounts: "the devil take all such reckonings!"

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published10 July 2017

- Published12 June 2017

- Published30 January 2017

- Published13 March 2017