The warrior monks who invented banking

- Published

Temple Church is not just an important architectural, historical and religious site

On London's busy Fleet Street, opposite Chancery Lane, is a stone arch through which anyone may step, and travel back in time.

A quiet courtyard houses a strange, circular chapel and a statue of two knights sharing a single horse.

The chapel is Temple Church, consecrated in 1185 as the London home of the Knights Templar.

But Temple Church is not just an important architectural, historical and religious site. It is also London's first bank.

The Knights Templar were warrior monks. A religious order, with a theologically inspired hierarchy, mission statement, and code of ethics, but also heavily armed and dedicated to holy war.

How did they get into the banking game?

Find out more

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that have helped create the economic world we live in.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

The Templars dedicated themselves to the defence of Christian pilgrims to Jerusalem. The city had been captured by the first crusade in 1099 and pilgrims began to stream in, travelling thousands of miles across Europe.

Those pilgrims needed to somehow fund months of food and transport and accommodation, yet avoid carrying huge sums of cash around, because that would have made them a target for robbers.

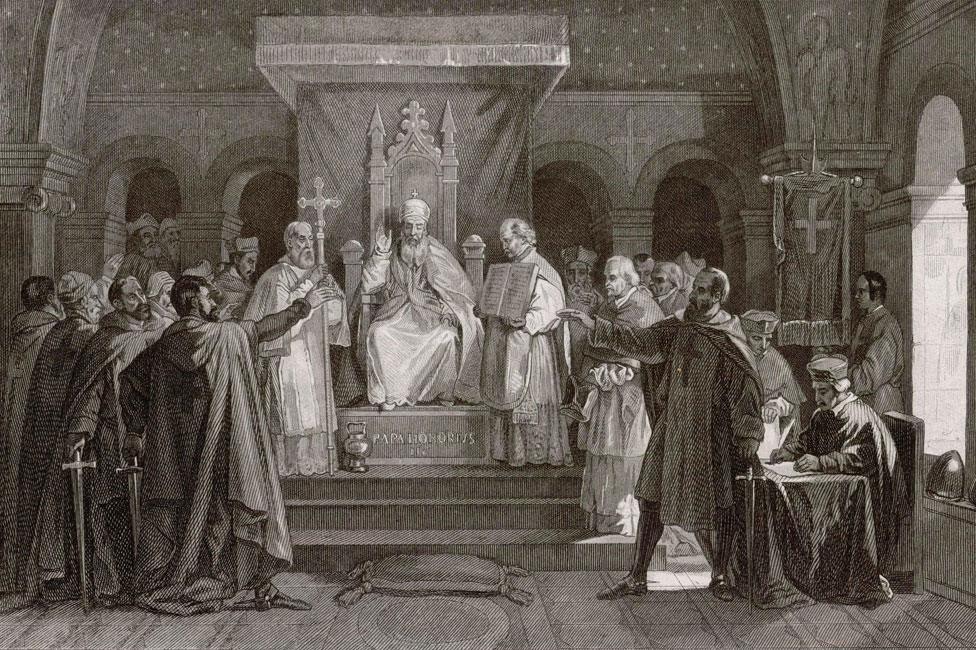

Pope Honorius II granted official recognition to the Knights Templar in 1128

Fortunately, the Templars had that covered. A pilgrim could leave his cash at Temple Church in London, and withdraw it in Jerusalem. Instead of carrying money, he would carry a letter of credit. The Knights Templar were the Western Union of the crusades.

We don't actually know how the Templars made this system work and protected themselves against fraud. Was there a secret code verifying the document and the traveller's identity?

Financial fixers

The Templars were not the first organisation in the world to provide such a service. Several centuries earlier, Tang dynasty China used "feiquan" - flying money - a two-part document allowing merchants to deposit profits in a regional office, and reclaim their cash back in the capital.

But that system was operated by the government. Templars were much closer to a private bank - albeit one owned by the Pope, allied to kings and princes across Europe, and run by a partnership of monks sworn to poverty.

King Henry III took advantage of the Templars' financial services

The Knights Templar did much more than transferring money across long distances.

As William Goetzmann describes in his book Money Changes Everything, they provided a range of recognisably modern financial services.

If you wanted to buy a nice island off the west coast of France - as King Henry III of England did in the 1200s with the island of Oleron, north-west of Bordeaux - the Templars could broker the deal.

Henry III paid £200 a year for five years to the Temple in London, then when his men took possession of the island, the Templars made sure that the seller got paid.

And in the 1200s, the Crown Jewels were kept at the Temple as security on a loan, the Templars operating as a very high-end pawn broker.

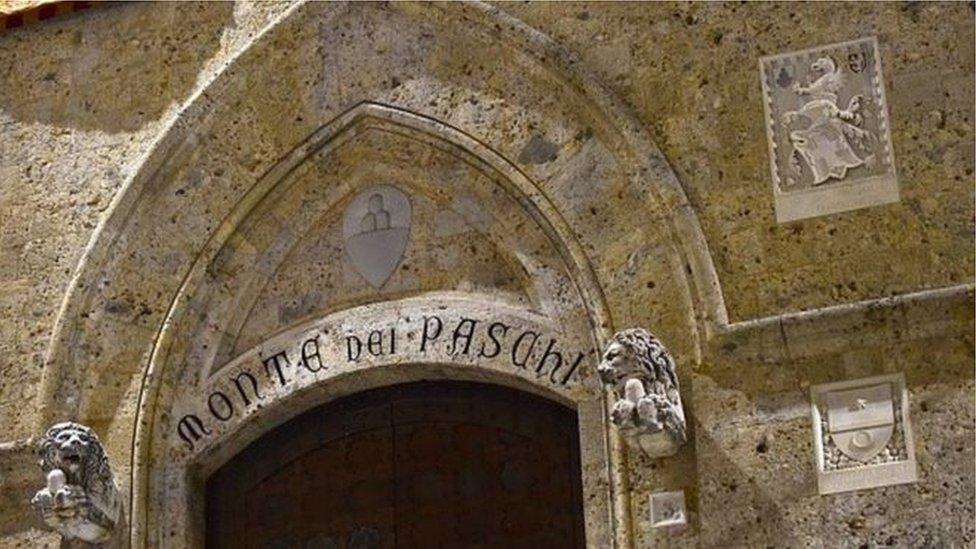

The Knights Templar were not Europe's bank forever, of course. The order lost its reason to exist after European Christians completely lost control of Jerusalem in 1244, and the Templars were eventually disbanded in 1312.

So who would step into the banking vacuum?

If you had been at the great fair of Lyon in 1555, you could have seen the answer. Lyon's fair was the greatest market for international trade in all Europe.

Sophisticated exchange

But at this particular fair, gossip was starting to spread about an Italian merchant who was there, and making a fortune.

He bought and sold nothing: all he had was a desk and an inkstand.

Day after day he sat there, receiving other merchants and signing their pieces of paper, and somehow becoming very rich.

The locals were very suspicious.

But to a new international elite of Europe's great merchant houses, his activities were perfectly legitimate.

He was buying and selling debt, and in doing so he was creating enormous economic value.

Bills of exchange allowed Florence's celebrated wool trade to flourish in the Middle Ages

A merchant from Lyon who wanted to buy - say - Florentine wool could go to this banker and borrow something called a bill of exchange. This was a credit note, an IOU, but it was not denominated in the French livre or Florentine lira.

Its value was expressed in the ecu de marc, a private currency used by this international network of bankers.

And if the Lyonnaise merchant or his agents travelled to Florence, the bill of exchange from the banker in Lyon would be recognised by bankers in Florence, who would gladly exchange it for local currency.

Through this network of bankers, a local merchant could not only exchange currencies but also translate his creditworthiness in Lyon into creditworthiness in Florence, a city where nobody had ever heard of him - a valuable service, worth paying for.

More from Tim Harford

Every few months, agents of this network of bankers would meet at the great fairs such as Lyon's, go through their books, net off all the credit notes against each other and settle any remaining debts.

Our financial system today has a lot in common with this model.

An Australian with a credit card can walk into a supermarket in Lyon and walk out with groceries.

The supermarket checks with a French bank, which talks to an Australian bank, which approves the payment, happy that this woman is good for the money.

Checks and balances

But this web of banking services has always had a darker side to it.

By turning personal obligations into internationally tradable debts, these medieval bankers were creating their own private money, outside the control of Europe's kings.

Rich, and powerful, they had no need for the coins minted by the sovereign.

The 2008 collapse of the Lehman Brothers bank led to financial instability across the globe

That description rings true even today. International banks are locked together in a web of mutual obligations that defies easy understanding or simple control.

They can use their international reach to try to sidestep taxes and regulations.

And, since their debts to each other are a very real kind of private money, when the banks are fragile, the entire monetary system of the world also becomes vulnerable.

We are still trying to figure out what to do with these banks.

We cannot live without them, it seems, and yet we are not sure we want to live with them.

Governments have long sought ways to hold them in check.

Sometimes the approach has been laissez-faire, sometimes not.

Few regulators have been quite as ardent as King Philip IV of France.

The last grandmaster of the Templars, Jacques de Molay, was burned to death in Paris in 1314

He owed money to the Templars, and they refused to forgive his debts.

So in 1307, on the site of what is now the Temple stop on the Paris Metro, Philip launched a raid on the Paris Temple - the first of a series of attacks across Europe.

Templars were tortured and forced to confess any sin the Inquisition could imagine. The order was disbanded by the Pope.

The London Temple was rented out to lawyers.

And the last grandmaster of the Templars, Jacques de Molay, was brought to the centre of Paris and publicly burned to death.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published13 January 2017

- Published13 January 2017

- Published27 December 2016

- Published25 November 2016