How the world's first accountants counted on cuneiform

- Published

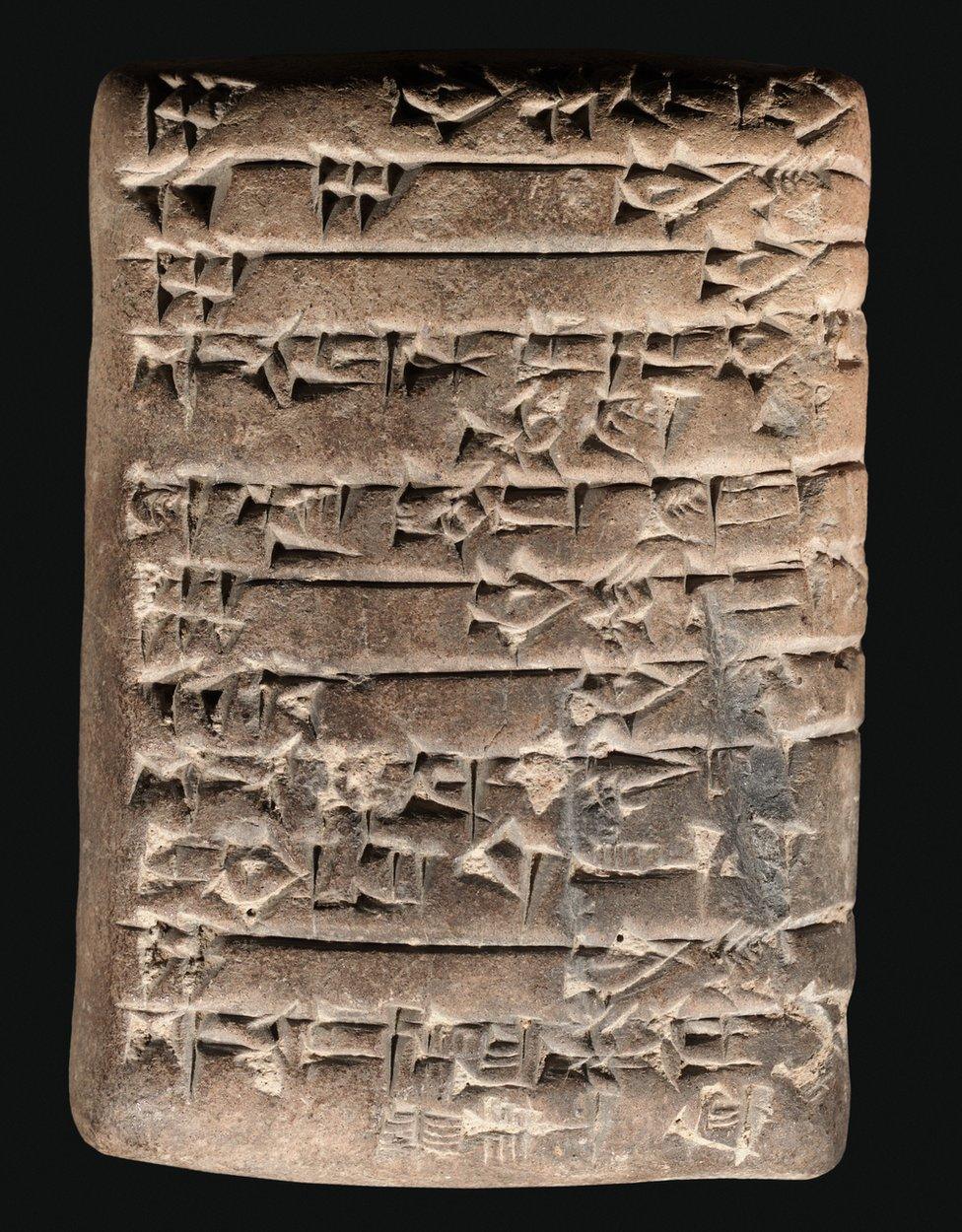

This tablet has an account in Sumerian cuneiform describing the receipt of oxen

The Egyptians used to believe that literacy was divine, a gift from baboon-faced Thoth, the god of knowledge.

Scholars no longer embrace that theory, but why ancient civilisations developed writing was a mystery for a long time. Was it for religious or artistic reasons? To communicate with distant armies?

The mystery deepened in 1929, when a German archaeologist named Julius Jordan unearthed a vast library of clay tablets that were 5,000 years old.

They were far older than the samples of writing already discovered in China, Egypt and Mesoamerica, and were written in an abstract script that became known as "cuneiform".

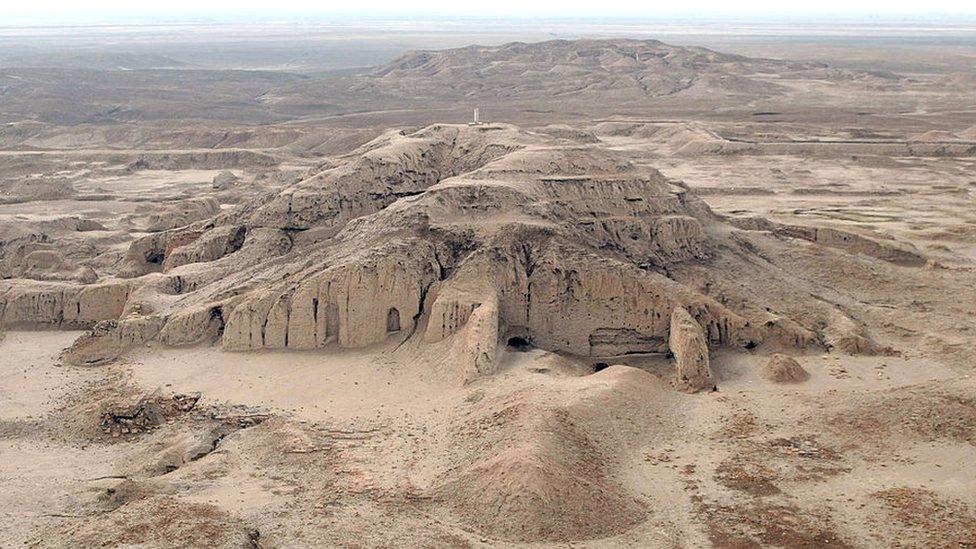

The tablets came from Uruk, a Mesopotamian settlement on the banks of the Euphrates in what is now Iraq.

The ruins of Uruk and other Mesopotamian cities were littered with mysterious little clay objects

Uruk was small by today's standards - with only a few thousand inhabitants - but in its time was huge, one of the world's first true cities.

"He built the town wall of 'Uruk', city of sheepfolds," proclaims the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the earliest works of literature. "Look at its wall with its frieze like bronze! Gaze at its bastions, which none can equal!"

This great city had produced writing that no modern scholar could decipher. What did it say?

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that have helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Uruk posed another puzzle for archaeologists - although initially it seemed unrelated.

The ruins of Uruk and other Mesopotamian cities were littered with little clay objects - conical, spherical and cylindrical. One archaeologist quipped they looked like suppositories.

Correspondence counting

Julius Jordan was a little more perceptive. They were shaped, he wrote in his journal, "like the commodities of daily life - jars, loaves, and animals", although they were stylised and standardised.

But what were they for? Nobody could work it out.

Nobody, that is, until the French archaeologist Denise Schmandt-Besserat.

In the 1970s, she catalogued similar pieces found across the region, from Turkey to Pakistan, some of which were 9,000 years old.

Denise Schmandt-Besserat - pictured here in Muscat in 2012 - is widely credited with discovering the origins of writing

Schmandt-Besserat believed the tokens had a simple purpose: correspondence counting. The tokens that were shaped like loaves could be used to count loaves. The ones shaped like jars could be used to count jars.

Correspondence counting is easy: you don't need to know how to count, you just need to look at two quantities and verify that they are the same.

The technique is older even than Uruk.

The 20,000-year-old Ishango Bone - found near one of the sources of the Nile in the Democratic Republic of Congo - seems to use matched tally marks on the thigh bone of a baboon for correspondence counting.

The 20,000-year-old Ishango Bone appears to show matched tally marks used for correspondence counting

But the Uruk tokens took things further: they were used to keep track of counting lots of different quantities, and could be used both to add and to subtract.

Urban economy

Remember, Uruk was a great city. There was a priesthood, there were craftsmen. Food was gathered from the surrounding countryside.

An urban economy requires trading, and planning, and taxation too. Picture the world's first accountants, sitting at the door of the temple storehouse, using the little loaf tokens to count as the sacks of grain arrive and leave.

Denise Schmandt-Besserat pointed out something else revolutionary. The abstract marks on the cuneiform tablets matched the tokens. Everyone else had missed the resemblance because the writing didn't seem to be a picture of anything.

But Schmandt-Besserat realised what had happened. The tablets had been used to record the back-and-forth of the tokens, which themselves were recording the back-and-forth of the sheep, the grain, and the jars of honey.

In fact, it may be that the first such tablets were impressions of the tokens themselves, pressing the hard clay baubles into the soft clay tablet.

Then those ancient accountants realised it might be simpler to make the marks with a stylus. So cuneiform writing was a stylised picture of an impression of a token representing a commodity. No wonder nobody had made the connection before Schmandt-Besserat.

Verification device

And so she solved both problems at once. Those clay tablets, adorned with the world's first abstract writing? They weren't being used for poetry, or to send messages to far-off lands. They were used to create the world's first accounts.

The world's first written contracts, too - since there is just a small leap between a record of what has been paid, and a record of a future obligation to pay.

These bulla, discovered in Iraq, recorded agricultural transactions in the 8th Millennium BC

The combination of the tokens and the clay cuneiform writing led to a brilliant verification device: a hollow clay ball called a bulla. On the outside of the bulla, the parties to a contract could write down the details of the obligation - including the resources that were to be paid.

On the inside of the bulla would be the tokens representing the deal. The writing on the outside and the tokens inside the clay ball verified each other.

We don't know who the parties to such agreements might have been - whether they were religious tithes to the temple, taxes, or private debts, is unclear. But such records were the purchase orders and the receipts that made life in a complex city society possible.

This is a big deal.

Most financial transactions are based on explicit written contracts. Insurance, a bank account, a government bond, a corporate share, a mortgage agreement - they're all written contracts - and the bullas of Mesopotamia are the very first archaeological evidence that written contracts existed.

Uruk's accountants provided us with another innovation, too.

More from Tim Harford

At first, the system for recording five sheep would simply require five separate sheep impressions. But that was cumbersome. A superior system involved using an abstract symbol for different numbers - five strokes for five, a circle for 10, two circles and three strokes for 23.

The numbers were always used to refer to a quantity of something: there was no "10" - only "10 sheep". But the numerical system was powerful enough to express large quantities - hundreds, and thousands.

One demand for war reparations, 4,400 years old, is for 4.5 trillion litres of barley grain, or 8.64 million "guru".

It was an unpayable bill - 600 times the US's annual production of barley today. But it was an impressively big number. It was also the world's first written evidence of compound interest.

In all it is quite a set of achievements.

The citizens of Uruk faced a huge problem, a problem that is fundamental to any modern economy - how to deal with a web of obligations and long-range plans between people who did not know each other well, who might perhaps never even meet.

Solving that problem meant producing a string of brilliant innovations: not only the first accounts and the first contracts, but the first mathematics and even the first writing.

Writing wasn't a gift from the gods. It was a tool that was developed for a very clear reason: to run an economy.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published13 March 2017

- Published30 January 2017

- Published16 November 2016

- Published9 March 2016

- Published14 June 2011