Would a bigger house make you happier?

- Published

The UK is often said to be experiencing a dire shortage of living space, but does having more room necessarily make people more content?

It is common to hear concerns about pokey new-builds and sky-high rents forcing people into ever smaller homes.

But the reality is that living spaces in England and Wales are actually larger than ever, with the average home increasing from 88 to 90 square metres, external between 2004 and 2016.

Instead, the issue is that the distribution of space has become more unequal.

Owner-occupiers often have a lot of space compared with younger renters, who may be sharing a home with several others. In 2017, about 28% of UK households contained one person, external, up from 17% in 1971.

Meanwhile, the proportion of families and individuals sharing private rented housing has almost tripled since 1992 to 6.6%, according to research by the Resolution Foundation think tank., external

So, does more space always mean happier occupants, or is there a cut-off point?

Status and the neighbours

A London-based colleague recently told me about her aunt coming to visit her from Hong Kong. Upon seeing her shoe-box bedroom, she was filled not with pity, but with envy. The aunt had grown up seven people to one room, and thought this living arrangement the height of luxury.

This illustrates how the level of space that we expect or aspire to can depend on what we are used to.

Even after people move to a bigger house, it may not take long for them to start to feel like they don't have enough.

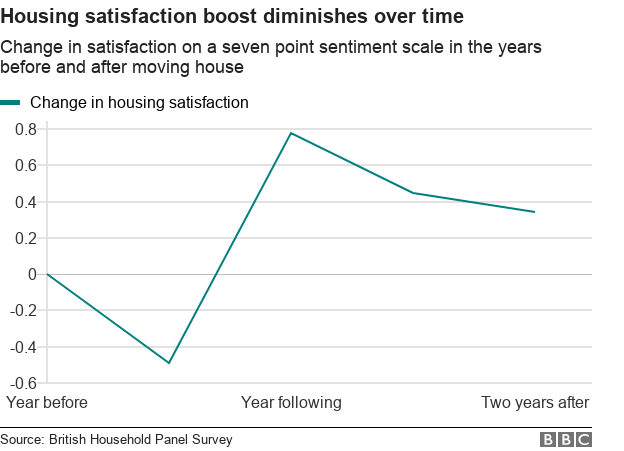

Surveying almost 1,000 people who chose to upsize their home, my research found, external that housing satisfaction initially increased after a move by 1.2 points on a seven-point scale.

But within three years, this rise had diminished by about 30% as people's space expectations increased.

You might think that people with very big houses would be more satisfied with their property.

But I found that any increase beyond four rooms per person resulted in no uplift in housing satisfaction at all.

This category is likely to include some older people who would like a smaller space but are reluctant to leave the family home.

But even for the average household, more space may not necessarily lead to more happiness.

Our space expectations are conditioned not only by where we have lived before, but also by our neighbours.

Because house size is a status symbol, we feel worse off when other people get larger houses.

A recent US study, external found that an increase in the size of the largest 10% of "superstar" houses had a significant negative effect on their neighbours, even if those people had also moved to bigger homes.

Previous surveys have suggested people would be prepared to have less living space overall, external if it meant they had more than others.

Are you 'normal'?

This is not to say that everyone is consciously competing with their neighbours over who has the biggest house.

Most of the concern about house size may stem from an underlying desire to fit in and do things which are considered "normal".

This could be having dinner around the family table or watching TV on the sofa - which requires us to have what we consider to be a "normal" level of living space. If home sizes increase then so does the amount of space we feel like we need just to keep up.

For example, if we all had space for a home gym then having friends round for a workout could well become as normal as having them round for dinner.

Counting the costs

As a nation, we do not seem to be getting any happier with our housing,, external even though living space and housing conditions, external have improved for many people.

The US-based study draws similar conclusions. It suggests that for people living in a detached house, satisfaction has stayed the same since the 1980s even as the amount of space per person has grown by about 40%, to more than 900 square feet.

Of course, more people moving into bigger homes does not come without costs.

Spending more on housing often means people incurring more mortgage debt, working longer hours, or commuting a longer distance, while building more homes has significant and irreversible environmental costs.

There is an overwhelming case for providing more genuinely affordable housing for those suffering the most cramped, unaffordable living conditions.

Beyond this, whether an increase in average living spaces would improve our wellbeing as a society is up for debate.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Dr Chris Foye is a knowledge exchange associate, external with the University of Glasgow, and the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence. His role involves building relationships between housing researchers, policymakers, practitioners and residents.

Edited by Eleanor Lawrie.