The real reason Father Christmas wears red and white

- Published

Eating KFC at Christmas is very popular in Japan - even in the air

A curious ritual takes place each year in Japan.

"Kurisumasu ni wa Kentakkii" - or "Kentucky for Christmas", is the habit of eating Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) on 24 December.

It began as an inspired bit of marketing in the 1970s, when KFC noticed that expatriates who craved Christmas turkey turned to fried chicken as the closest available substitute. Now a popular Japanese tradition, customers queue around the block, and some pre-order their meal as early as October.

Christmas, of course, is not a religious holiday in Japan, where a tiny minority of the population is Christian.

But "Kurisumasu ni wa Kentakkii" demonstrates how easily commercial interests can hijack religious festivals - from Diwali in India to Passover in Israel, but most notoriously, Christmas in America.

Why, after all, does Santa Claus wear red and white?

Many people will tell you that the modern Santa is dressed to match the red-and-white colours of a can of Coke, and was popularised by Coca Cola's advertising in the 1930s.

A good story, but the red-and-white Santa himself wasn't created to advertise Coca-Cola - why, he was touting the rival beverage White Rock back in 1923.

Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer was the one who was invented as a marketing gimmick.

The modern Santa Claus is actually much older, a patchwork character woven together from different sources.

These include Saint Nicholas, a 4th Century Greek bishop - who famously wore red robes while giving gifts to the poor, especially children - and the English folk figure "Father Christmas", whose original green robes turned red over time.

The Santa we know also owes much to the Dutch figure Sinterklaas - also based on Saint Nicholas - whose legend flourished in the once-Dutch city of New York, popular with prosperous Manhattanites such as Washington Irving and Clement Clarke Moore in the early 1800s.

Mr Irving and Mr Moore also wanted to turn Christmas Eve from a raucous partying of street gangs into a hushed family affair, everyone tucked up in bed and not a creature stirring - not even a mouse.

Mr Moore - who penned the line "'Twas The Night Before Christmas" in 1823 - did as much as anyone to create the American idea of Santa Claus, the red-robed patron saint of giving presents to everyone whether they want them or not.

It was in the 1820s, too, that advertisements for Christmas presents became common in the United States. By the 1840s, Santa himself was a frequent commercial icon in advertisements. Retailers, after all, had to find some way to clear their end-of-year stock.

The gift-giving tradition took firm hold.

In Boston in 1867, 10,000 people paid to see Charles Dickens give readings of his Christmas Carol - a story light on biblical details and heavy on the idea of generosity.

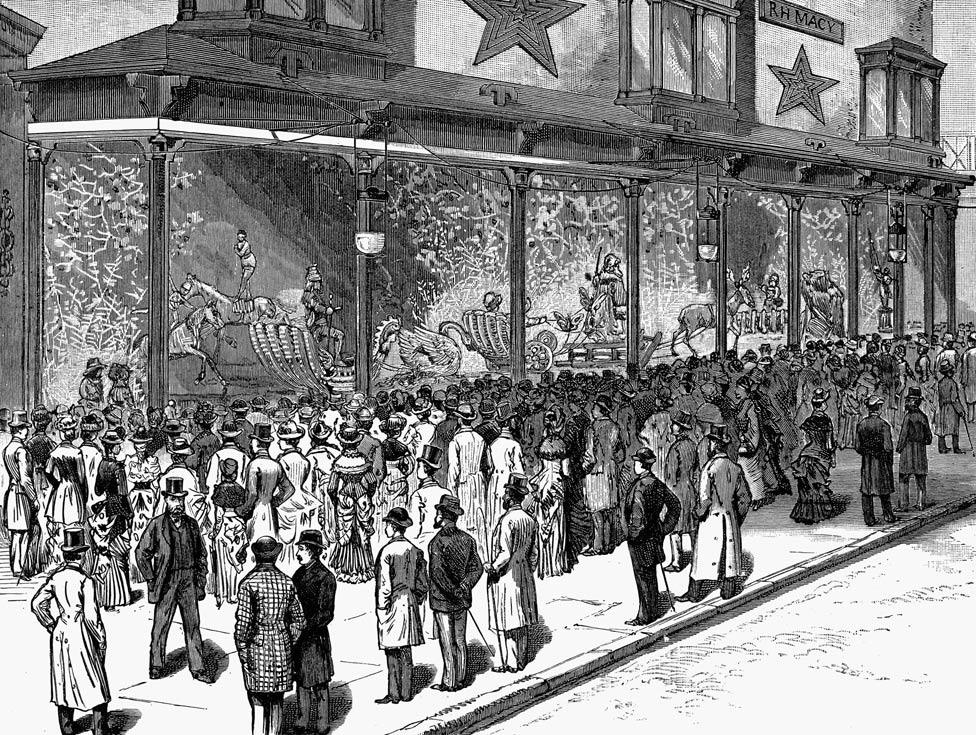

Down the coast in New York the same year, Macy's department store decided it was worth keeping the doors open until midnight on Christmas Eve, for last-minute Christmas shoppers.

Macy's in New York became famous for its spectacular Christmas window displays

The next year, Louisa May Alcott's novel Little Women was published. Its first line: "Christmas won't be Christmas without any presents."

The Christmas blowout, then, is not new.

Prof Joel Waldfogel, an economist and author of Scroogenomics, has been able to track the impact of Santa on the US economy back across the decades.

By comparing retail sales in December with sales in November and January, Prof Waldfogel has estimated the size of the Christmas spending bump all the way back to 1935, the era of the Coca-Cola Santa.

In fact, relative to the size of the economy, Christmas spending was three times bigger then than now. What is an everyday indulgence today would have been a once-a-year treat back in the 1930s.

Prof Waldfogel has also compared the US Christmas boom to other high-income countries around the world. Again, perhaps surprisingly, the US's December spending boom is not particularly large, relative to other countries.

Portugal, Italy, South Africa, Mexico and the United Kingdom have the largest Christmas retail boom relative to the size of their economies; the US is an also-ran.

Find out more

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

In the grand scheme of things, Christmas is a modest affair, financially speaking.

In the US, for every $1,000 (£790) spent across the year, only $3 is specifically attributable to Christmas. After all, you would have lunch anyway, pay your rent, fill your car with petrol and buy clothes to wear.

However, for certain retail sectors - notably jewellery, department stores, electronics, and useless tat - Christmas is a very big deal indeed.

A small fraction of a big number is still a big number - Prof Waldfogel reckons that at least $60bn or $70bn is spent on Christmas in the United States alone, and perhaps $200bn around the world.

Is that money well spent?

"There are worlds of money wasted, at this time of year, in getting things that nobody wants, and nobody cares for after they are got." So said the author of Uncle Tom's Cabin, Harriet Beecher Stowe, back in 1850 - an early example of what is now a common complaint.

Economists and moralisers do not often find themselves having common cause, but on the subject of Christmas we do: we agree that a lot of Christmas spending is wasteful.

Time, energy and natural resources are poured into creating Christmas gifts which the recipients often do not much like.

More from Tim Harford

Santa's gifts rarely miss the mark; he is, after all, the world's number one toy expert. The same cannot be said of the rest of us.

Prof Waldfogel's most famous academic paper The Deadweight Loss of Christmas, external tried to measure the gap between how much various Christmas gifts had cost, and how much the recipients valued them - beyond the warm glow of "the thought that counts".

He concluded that the typical $100 gift was valued at - on average - only $82 by the recipient.

This wastage figure seems to be fairly robust across countries. Two Indian economists who estimated the equivalent "deadweight loss" of Diwali, external suggested that $35bn is being wasted around the world in the form of poorly-chosen Christmas gifts.

To put it into context, that is about what the World Bank lends to developing country governments each year.

This is real money and it is really being wasted.

Much retail spending is now squeezed into the period between Black Friday and Christmas

And that is before pondering the strain put on the economy by squeezing the retail spending together in a single month rather than spreading it out - and the time and aggravation devoted to the process of shopping, which is not always pleasant during the December rush.

So other economists have examined alternatives to clumsy gift giving.

Gift cards and vouchers do not help as much as one might hope: they are often unredeemed, or resold online at a discount. If you must buy a gift card, note that vouchers for lingerie sell well below face value on eBay, but vouchers for office supplies and coffee hold up pretty well.

Wishlists fare better. Research suggests that recipients are generally delighted to receive an item they have already specified. Givers may be deceiving themselves to think an off-piste gift will be more welcome.

Santa Claus relies on a polite wishlist from good children. Who are the rest of us to think we can do better?

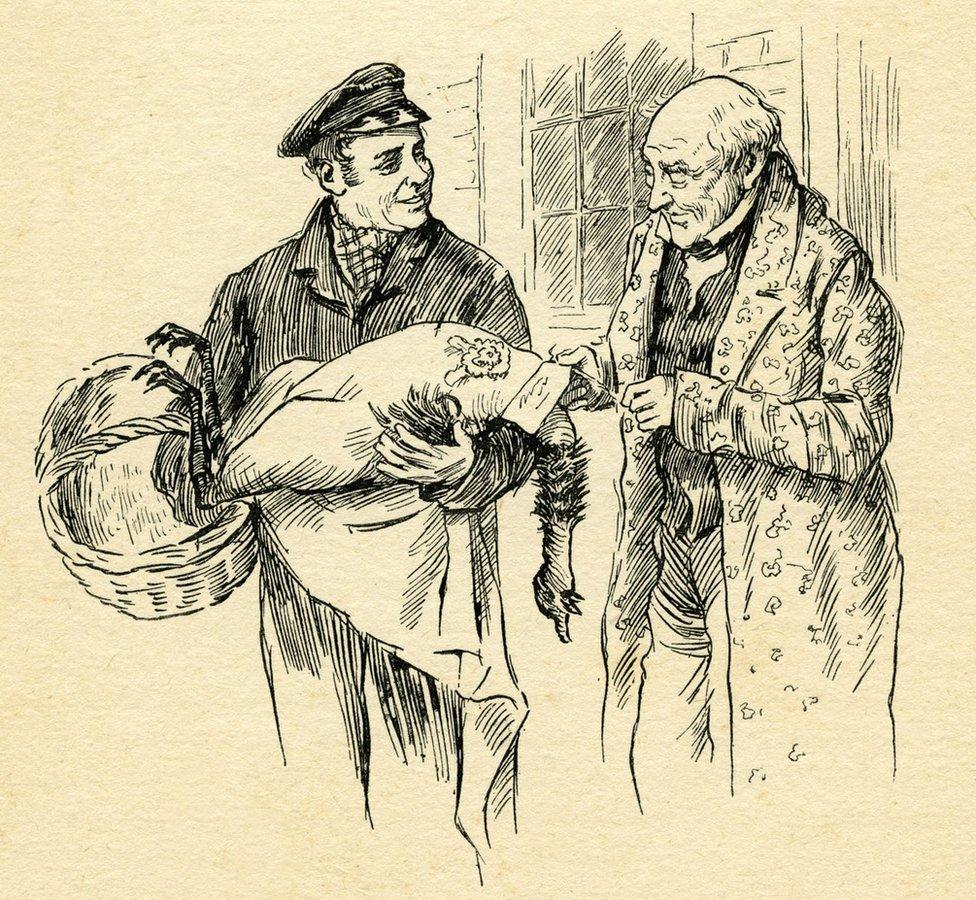

Dickens' Ebeneezer Scrooge famously encounters three ghosts who help him understand the "true" value of Christmas

Or we could learn from the reformed Ebenezer Scrooge, who, Dickens declares, "knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge".

On Christmas morning, the only physical gift he gave was a prize turkey. The Christmas spirits had shown him that the turkey was sorely needed.

Other than that, he gave people his company and his money - including a rise for Bob Cratchit.

Money! That's the true spirit of Christmas. God bless us, every one!

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy was broadcast on the BBC World Service.

You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published14 December 2018

- Published13 December 2018

- Published9 December 2016

- Published7 December 2016

- Published10 December 2015