Are you happy to share your health data to benefit others?

- Published

Could AI-powered health apps and remote consultations reduce unnecessary visits to the doctor?

From automated eye scans to analysing the cries of new-born babies, faster drug development to personalised medicine, artificial intelligence (AI) promises huge advances in the field of healthcare. But major challenges remain.

At the recent AI for Good Summit in Geneva, Switzerland, we were told how AI could speed up the development of new drugs, lead to personalised medicine informed by our genomes, and help diagnose diseases in countries suffering from underdeveloped health services and a chronic shortage of doctors.

But there are two main obstacles preventing access to this utopian destination.

One is that the AI being applied to the world's health problems isn't quite good enough yet. The other related issue is the lack of good quality digital data - less than 20% of the world's medical data is available in a form that AI machine learning algorithms can ingest and learn from, the WHO estimates.

As populations grow and age, more pressure is being put on doctors who are struggling to cope with the increase in administration that comes with more patients wanting to be seen more often. And in emerging economies, there simply aren't enough doctors to go around.

So many companies have been developing health advice and symptom checker apps as a way of filling the gap.

"Studies in the UK have found that 20% of people who go to the doctor don't really need to be there - the appointments are for minor ailments and injuries that could have been sorted by other means," explains Jonathon Carr-Brown, head of partnerships for Your.MD, a health information and symptom checker app.

WATCH: Could artificial intelligence replace doctors?

But the rise of such apps has caused concern among health professionals.

Last year, for example, Babylon, the company behind the UK's National Health Service app GP at Hand, caused a row by claiming its AI-powered chatbot was as good as a doctor - a claim that was disputed.

This is perhaps why companies like Microsoft, which has developed a chatbot or "virtual assistant" specifically for the healthcare sector, are being careful not to exaggerate the abilities of their creations.

"It's certainly not a replacement for your doctor, more of a support," explains Hadas Bitran, head of Microsoft Healthcare Israel.

"We want to help doctors decide who they need to help first. It's like a rule-based textbook for triage."

For Ai to reach its full potential more patients will need to share their health data

The chatbot comes equipped with medical content provided by trusted third parties, general symptoms checking capability, and natural language processing that can discern whether or not a patient is upset. If it detects heightened emotion it will refer the case to a human, says Ms Bitran.

Your.MD's Mr Carr-Brown also emphasises that his firm's app is not a replacement for a doctor.

"Just because AI can diagnose, that doesn't mean it should always do it. We need to focus on next steps advice rather than diagnosis, so we're moving to being more of a guide and companion."

It's a telling admission.

Dr Soumya Swaminathan, the World Health Organisation's (WHO) first chief scientist, believes there should be a global governance framework for AI in health. Indeed, the WHO and the International Telecommunications Union (hosts of the AI for Good Summit) have set up a joint focus group to look at how standards for AI in healthcare could be established.

"There is a risk that unevaluated apps could end up doing more harm than good," she warns.

But in emerging markets, where there are fewer doctors to go around, such virtual assistants and AI-powered apps could provide remote care, linking people up to doctors via video link and providing initial diagnoses, argues Ms Bitran, thereby preventing many wasted journeys over long distances.

"830 women are lost every day to problems in pregnancy and child birth, 90% in sub-Saharan Africa," says Alvin Kabwama, head of applied machine learning at Cognitive AI Tech Limited.

"They don't get access to essential urine tests other mothers get routinely in other parts of the world."

Sometimes the women have to walk 27km to the nearest health centre - a journey of five hours. "If she arrives late and the doctors have left, she has to walk back home," he says.

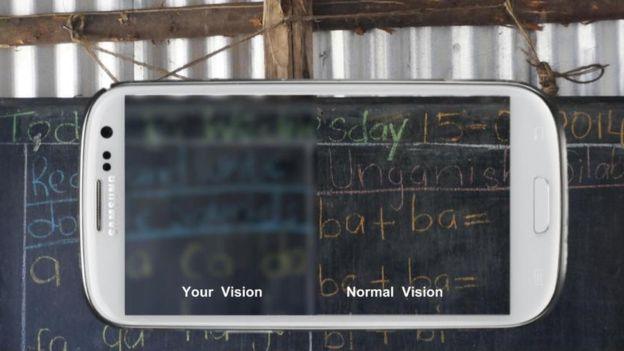

Smartphones are being used to diagnose poor eyesight and other conditions in remote areas

So in remote areas, smartphones are increasingly being used as diagnostic tools, testing eyes, ears, skin conditions and so on, and AI-powered machines are speeding up the diagnosis of urine and blood samples.

However, AI needs vast amounts of data to learn from and electronic health records are not the norm in many countries, making AI analysis even more difficult.

"In Senegal there is still a big reliance on paper forms that are often incomplete or illegible," says Ibrahima Khaliloulah, a doctor working in the country.

"Full electronic health records are essential, a goal Senegal hopes to achieve by 2030."

But even in developed countries, lack of access to digital health data is a big problem.

"Health data is a public good, but people have to trust the WHO and governments that it won't be used for commercial reasons without their consent or to discriminate against people," says the WHO's Soumya Swaminathan

And this is the dilemma.

People are particularly sensitive about sharing health data - even in anonymised form - yet AI needs as much data as possible to spot patterns humans can't, diagnose diseases more accurately, and target treatments more effectively.

AI is good at finding molecules with the potential to be developed into drugs, but these eventually have to be tested on humans in clinical trials, and finding suitable candidates is hugely expensive and time-consuming.

"About 80% of trials fail to meet their deadlines because they couldn't find suitable patients in time," says Microsoft's Ms Bitran, "and half never meet their recruitment targets".

Huge global databases of anonymised health data could help match patients with clinical trial requirements much more efficiently, thereby speeding up how quickly potentially life-saving drugs come to market.

So to maximise the undoubted benefits of AI in healthcare, we need to digitise as much health data as possible and persuade the world to share this data for the good of all.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external