The 'microworkers' making your digital life possible

- Published

Who are the "microworkers" behind your digital life?

"I used to have an office but sadly I had to close it down," says former dentist Michelle Muñoz of her life amid crisis-hit Venezuela.

With a collapsed economy and hyperinflation, "people don't have enough money to afford a dentist and have to worry about food, education and other things", she adds.

Two years ago she swapped her dental practice for online work as part of the global army of hidden "microworkers" - performing tasks that machines alone cannot.

Think of a day in your "digital life". Whether it's your phone's search engine recommending relevant restaurants or a music app's suggested playlist - none of this would be possible without microworkers.

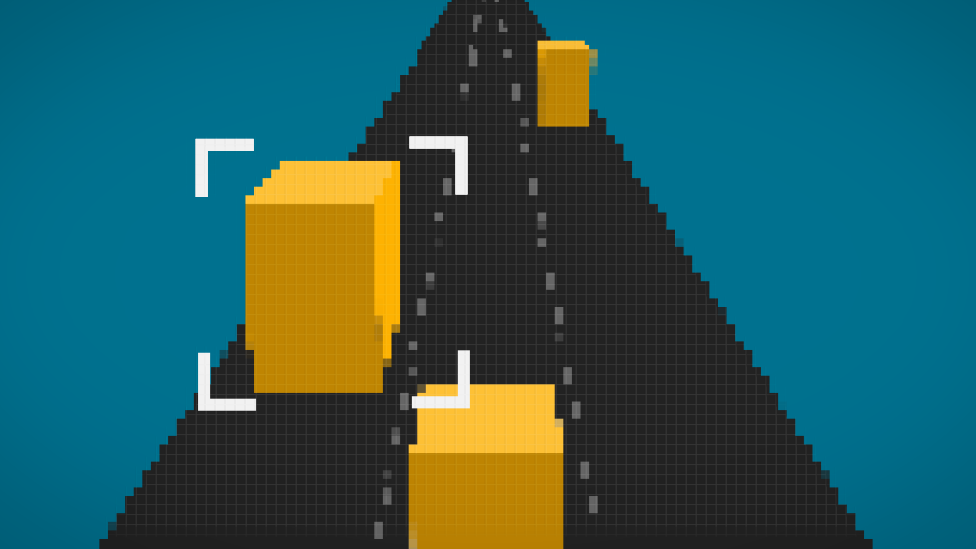

Microworkers like Michelle from Venezuela undertake simple, repetitive tasks online - such as drawing round a face to help train artificial intelligence systems to recognise people

They help provide data for machine learning algorithms that are the basis of artificial intelligence (AI) by adding the human element.

They might draw bounding boxes around footage of roads to teach driverless cars what a tree, obstacle or a moving person look like, or tag content with feelings so algorithms can learn what a "sad" song sounds like or whether a text or word is "worrying."

This work often gets a bad press as it's seen as poorly paid, but for many it is a solution. Michelle says microworking has been her only way of earning an income: "I do much better with this than as a dentist."

She tells the BBC of a good day when she earned about $80, which she used to buy the smartphone she now uses to work.

The 18th Century Mechanical Turk fooled chess players into thinking they were competing against a machine

Back in 2005, Amazon's CEO Jeff Bezos called crowdsourced microwork the "artificial artificial intelligence" when he set up the Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) the world's first crowdsourcing marketplace. It was named after an 18th Century hoax that fooled chess players into thinking they were competing against a machine, instead of the chess master hiding inside a large wooden box with a dummy on top.

Amazon first used it to weed out millions of duplicate pages as computers could not notice subtle differences. But as no one person could do this, they broke it down into small tasks that could be completed by thousands of workers.

There are no official numbers for how many microworkers there are, but tens of thousands are estimated to work on Amazon's MTurk every month, with up to 2,500 being active at any given time, external - mostly in the US and India.

An International Labour Organisation (ILO) survey of 3,500 microworkers in 75 countries, external found the average age was 33 and a third were women, though this dropped to a fifth in developing countries.

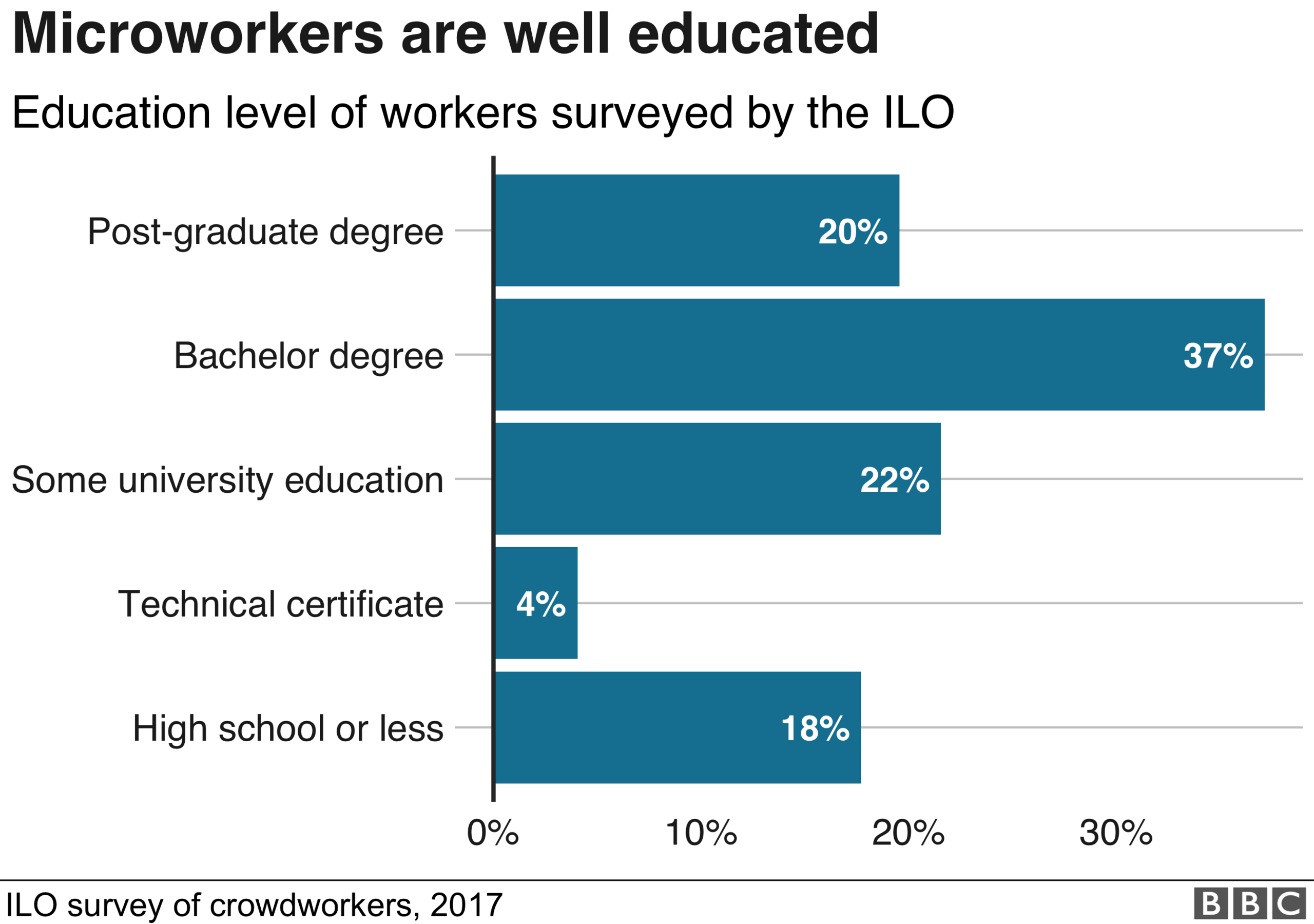

Microworkers are also educated: fewer than 18% had a high-school diploma or less, 37% had a graduate degree, 20% a postgraduate degree; more than half specialised in science and technology, 23% in engineering and 22% in IT.

For those in countries in crisis, microwork can be especially useful.

Yahya: "This allows you to work without having to apply and send a CV"

Yahya Ayoub Ahmed is a Syrian who fled the civil war and is now in the Darashakran refugee camp in Erbil, Iraq. In the camp, an organisation called Preemptive Love taught him the English and IT skills allowing him to become a microworker.

"You can use it remotely and generate income. Over here applying for a job is quite difficult, it's not like you can just Google a job," he says. "This allows you to work without having to apply and send a CV."

But there is an extra hurdle for workers in countries like Iraq, as tasks are mainly aimed at developed countries, says Allen Ninous of Preemptive Love.

"Most online crowdsourcing services restrict Iraqis from registering, and even if one could magically do so, there's no method of cashing out the wages since all withdrawals take place through a third party online banking system such as PayPal."

So they have to resort to special agreements with firms to overcome this.

It is even harder for people who work on their own from home. Venezuelan microworker Rafael Pérez describes a similar situation of being filtered out of many tasks he sees being posted.

Microworkers provide data for machine learning used in technology like driverless cars

He has also lost money many times from unscrupulous requesters who didn't pay him: "Once I earned $180 in 15 days - a lot of money - and they never paid. I emailed, I called - but you don't have anyone to complain to."

Michelle says at the beginning she too fell for scams, but she now puts websites through a test period before working with them.

Microwork has come under scrutiny because of poor pay: the ILO found workers earned an average of $4.43 an hour. And while US workers earnt an average of $4.70 (still lower than the minimum wage) workers in Africa got just $1.33 an hour.

Per hour of paid and unpaid work

US$4.70Northern America

US$3.00Europe

US$2.22Asia and the Pacific

US$1.33Africa

And these figures don't take into account workers spending an average of 20 minutes on unpaid activities for every hour of paid work.

This includes searching for tasks and answering test questions set by the requester for quality control. "I spend most of the day looking for tasks. Once one comes in, I have to sit down and do it," says Rafael.

Rafael says on a good day he can make about $8-10 a day. It means he can buy a small box of eggs, a kilo of cornflour and a kilo of beans. "You will not live very well, but you will eat well," he says.

Microwork is invisible to the many, and has attracted little public attention

Professor Paola Tubaro of CNRS, France's national scientific research centre, says microworking is not a temporary phenomenon but structural to the development of new technologies like AI, external.

"Even if machines learn, say, how to recognise cats and dogs, you still need to feed them more details to recognise." As these technologies expand so will the need for people to feed in the data, she says.

Currently there is no government regulation of microwork platforms, though the ILO has called for better regulation of the sector to ensure minimum wages and better payments transparency, are met.

"Microwork is invisible to the many and has attracted little public attention," argues Prof Tubaro.

"It cannot be fair if these people aren't paid enough or have no kind of social protection. If people work under the same conditions as 19th Century factories that's not something that our society would accept as right."

Back in Venezuela, Michelle agrees. She says there should be more "support and recognition" for microworkers. She says its the platforms that make the money from their work. "What we are being paid - at least here in Venezuela - is little."

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external