How 3D technology is capturing the world

- Published

With enough pictures and clever software you can catch immense detail

London design studio Sample & Hold has been asked to scan all kinds of things: a shoe, a carrot, the heads of every member of the Barcelona FC team.

The firm has even worked with a company in Knightsbridge, London, that makes casts of babies' feet and heads.

"Occasionally they have a client who wants a head scan of their kid," explains Sample & Hold director Sam Jackson.

Those scans have been used for bronze casts of the child's head, and the 3D scan speeds up that process.

Sample & Hold doesn't need lasers to do this 3D scanning. Instead, it uses plain old 2D cameras. The trick is to use lots of them - 67 in total.

Photogrammetry software combines data from multiple pictures

The subject, or object, is placed in a rig with each camera positioned in a sort of photographic sphere around them. With the click of a button, an image is captured from 67 different angles. These can then be merged together in computer software to form a 3D model.

It is called photogrammetry, the process of simultaneously capturing visual and spatial information. As a technology it is surprisingly old. People have been experimenting with different forms of it for more than 150 years but it is currently "having a moment", in part thanks to the low cost of digital cameras.

Different 3D scanning technologies have different strengths. As Mr Jackson explains, photogrammetry is particularly good at capturing the visual quality of objects.

"It's the colour information that's the important part," he says. Sometimes, though, the technique does not work quite as well as intended - for example with people whose skin is exceptionally smooth and clear.

"We've been in situations with models coming in who have very uniform skin, no blemishes whatsoever, it's very difficult to capture that kind of skin."

I explain that he would have no trouble scanning me in this regard.

Photogrammetry was used in the production of the latest Call of Duty computer game

Photogrammetry is increasingly being used to insert lifelike character models into video games and to digitise real-world scenery.

The designers working on Call of Duty: Modern Warfare have been praised for the "gritty" quality of the title's in-game environments. Photogrammetry helped to achieve that.

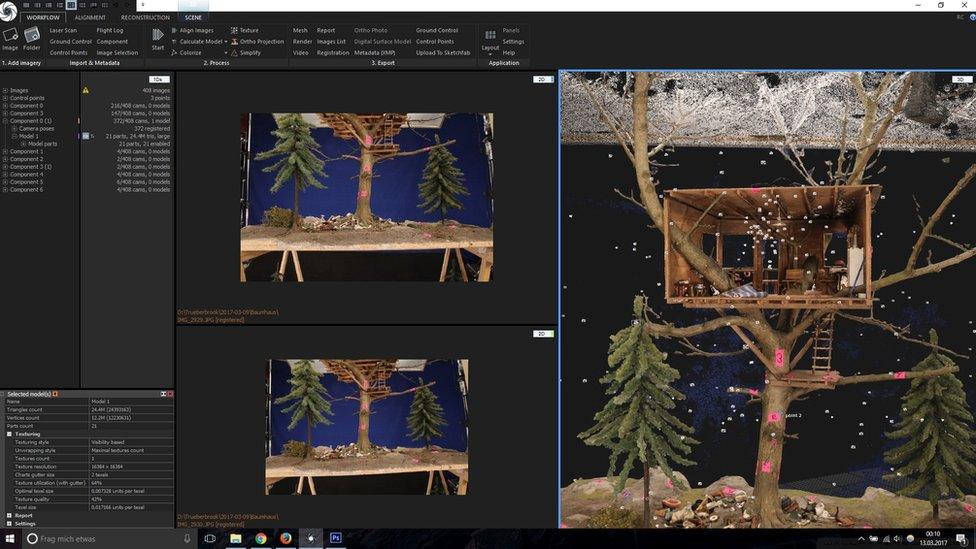

And a recent indie game, Trueberbrook, features scenes that were handmade as real models and then scanned in a variety of different light settings using photogrammetry. These were then digitised.

Other industries are now turning to photogrammetry to make cheap, 3D surveys of large sites or facilities. Often, this involves flying a small camera-equipped drone around the structure in question so that photographs can be taken from many angles.

"Everybody has a camera and cameras have dropped dramatically in price," explains Jan Boehm, an expert in photogrammetry at University College London.

Uplift Drones, a British company that trains drone operators, offers courses in aerial photogrammetry.

Instead of sending staff up onto council building roofs to check them, some local authorities in the UK are now using drones to scan them in 3D instead, says James Dunthorne, a consultant for Uplift.

Scan of Christ the Redeemer statue in Rio de Janeiro

"Instead of inspecting the asset physically it can be done on a computer," he explains.

Some clients he has worked with are taking photogrammetry to the next level by attaching exceptionally high-resolution cameras to drones. These are large pieces of equipment that traditionally would have been fixed to the underside of planes or helicopters.

Rail companies, for instance, use such cameras to make ultra-detailed 3D models of track. Staff can then check that the track is in place with all crossings and switches correctly aligned.

"The quality of data you're able to achieve from that is breathtaking," says Mr Dunthorne. "I'd call it photogrammetry on steroids."

Drone-based photogrammetry is cropping up everywhere. In the US, the Washington state transport department's aviation division recently trialled the technology as a means for detecting obstructive objects on the runway at two airports, Prosser Airport and Sunnyside Municipal Airport.

Industry combines drones and photogrammetry for high-definition 3D images

A spokeswoman for the department confirms to the BBC that the work will continue.

"We recently purchased our own drone with the intent to do our own work for photogrammetry versus hiring a contractor," she says.

Often, though, third-party contractors provide the drones or software to make photogrammetry surveys possible.

Pix4D, headquartered in Switzerland, makes software that converts aerial photographs into 3D models. Every year, the total area mapped by people using that software increases, explains spokeswoman Nikoleta Guetcheva.

"In 2018, our users mapped more than 450,000 sq km," she says. "This is ten times Switzerland."

Ms Guetcheva explains that this 3D mapping includes mines, farmland, communication towers, pipelines and even underwater assets.

Pix4D's clients like to make regular surveys of, for example, construction sites so that progress can be shown clearly in 3D. Or, a mining company might use photogrammetry to take measurements of the huge piles of earth or raw materials that are constantly being excavated.

"We've seen a great improvement in cameras in recent years… The stabilisation of drones is better and better," says Ms Guetcheva.

Depending on what you want to scan, and where, you might turn to a fixed wing or rotary wing drone. Fixed wing devices have a longer range but need adequate space to take off and land safely.

Polish firm FlyTech UAV makes a drone it calls "Birdie" that can be transformed from a fixed wing to vertical take-off and landing version with some attachments.

The company has recently helped utility firms make large 3D models of electricity cables and pylons. It's much cheaper than sending up a helicopter to do the same surveys, FlyTech says.

It's a way of mapping the world - one photograph at a time.