What happens when we're too old to be 'useful'?

- Published

"I customarily killed old women. They all died, there by the big river. I didn't used to wait until they were completely dead to bury them. The women were afraid of me."

No wonder. That's the account of a man from the Aché, an indigenous tribe in eastern Paraguay, as told to anthropologists Kim Hill and Magdalena Hurtado.

He explained grandmothers helped with chores and babysitting but when they got too old to be useful, you couldn't be sentimental.

The Aché are nomadic hunter-gatherers who traditionally lived in small groups, relying on wild forest resources for their survival

Brutally, the usual method was an axe to the head. For the old men, Aché custom dictated a different fate. They were sent away - and told never to return.

What obligations do we owe to our elders? It's a question as old as humankind.

And the answers have varied widely, at least if surviving traditional societies are any guide.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

As another anthropologist, Jared Diamond, points out, the Aché are hardly outliers. Among the Kualong, in Papua New Guinea, when a woman's husband died, it was her son's solemn duty to strangle her.

In the Arctic, the Chukchi encouraged old people to kill themselves with the promise of rewards in the afterlife.

A young Chukchi child with a sledge

But many other tribes took a very different approach: they were gerontocracies, in which the young do as the old say.

Some even expected adults to pre-chew food for their aged and toothless parents.

What does seem common is the expectation that, until your body let you down completely, you'd keep working. That's no longer true.

Many of us expect to reach a certain age, then receive a pension - money from the state or our former employers, not in return for work today but in recognition of our work in the past.

Pensions for soldiers date back at least as far as ancient Rome - the word "pension" comes from the Latin for "payment".

But only in the 19th Century did they spread far beyond the military. The first universal state pension came in Germany in 1890, thanks to the efforts of the German Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck

Bismarck told the German parliament in 1881 those who could not work because of age or ill health had a "well grounded claim to care from the state"

But the right to support in old age is still far from global.

Nearly a third of the world's older people have no pension, external and for many of the rest who receive some money, the pension is not enough to live on.

In many countries, however, generations have grown up assuming they will be well looked after in old age.

But it's becoming a challenge to meet that expectation.

And for years, economic-policy experts have been sounding the alarm about a slow-burn crisis in the pension system.

The problem is demographic. Half a century ago, in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a club of rich nations, the average 65-year-old woman could expect to live about 15 more years. Today, she can expect at least 20, external.

Meanwhile, the average family has shrunk from 2.7 children to 1.7, external - the pipeline of future workers is drying up.

All that has many implications, some good and some bad.

Pensions depend on contributions from current workers

But for pensions, the situation is stark - there'll be many more retirees to support and many fewer workers paying taxes to support them. In the 1960s, the world had nearly 12 workers for every older person. Today, it's under eight - and by 2050, it'll be just four, external.

Both state and private pension systems now look expensive. Employers have been scrambling to make theirs less generous. Forty years ago, most American workers were on so-called "defined-benefit" plans, which specify what you'll receive when you retire. Now, it's fewer than one in 10.

The new norm, "defined-contribution" schemes, specify what your employer will pay into your pension pot rather than what income you'll be able to get out of it. Such pensions don't logically have to be more miserly than defined-benefit schemes - but they usually are, often vastly so.

It's easy to understand why employers are ditching defined benefits - pension promises can prove expensive to keep.

More things that made the modern economy:

Ponder the case of John Janeway, who fought in the US Civil War.

His military pension included benefits for a surviving spouse when he died. When Janeway was 81, he married an 18-year-old. The army was still paying Gertrude Janeway her widow's pension in 2003, external, nearly 140 years after the war ended.

Economists can see trouble ahead - a bulge of workers is approaching retirement and their workplace pensions may be worth less than they'd expected. That's why governments around the world are trying to persuade individuals to save more themselves, external towards their old age.

But it's not easy to persuade people to focus on the distant future. One survey suggests under-50s are barely half as likely as over-50s to say retirement is their top financial concern.

When you're saving for your first house or raising a young family, you may not feel a pressing need to provide for the old person you'll one day become. Indeed, you may find it hard to conceive of that future old person as you.

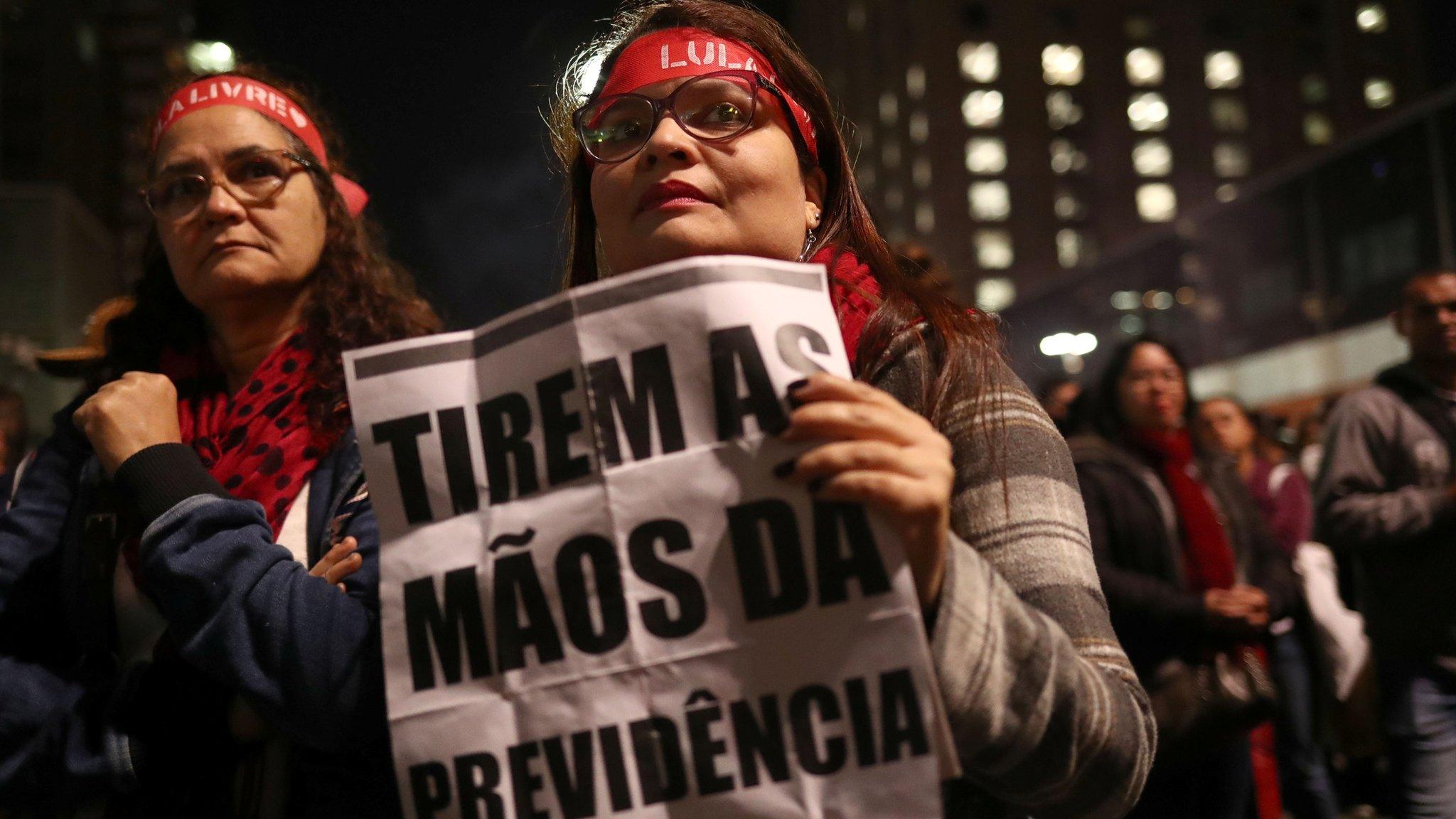

Paris Opera dancers joined widespread protests against President Macron's proposed pension changes in December

Behavioural economists have come up with some clever solutions, such as automatically enrolling people in workplace pension schemes and scheduling more saving from future pay rises. These "nudges" work pretty well - we could opt out but instead we tend to save through sheer inertia.

But they don't solve the fundamental demographic problem.

No amount of saving changes the fact we'll always need current workers to generate the wealth to support current pensioners - whether that's through paying taxes, renting properties owned by retirees, or working for companies in which pension funds are the major shareholders.

Some think we'll need a more radical shift in our attitudes to old age. There's talk of retirement itself being "retired", external. Perhaps, like our ancestors, we'll be expected to work for as long as we're able.

But the varied customs of ancestral societies should give us pause, because they appear to have evolved in response to some discomfortingly hard-nosed trade-offs.

Whether elders could expect lovingly pre-chewed food or an axe by the big river seems to have depended on whether the benefits they offered the tribe outweighed the costs of supporting them.

In tribes such as the Aché, those costs were higher - because they moved around a lot or food was frequently scarce.

Today's societies are rich and sedentary by comparison - we can afford the rising cost of pensions, if we choose.

But there are other differences, too. Once we relied on elders to store knowledge and instruct the young. Now, knowledge dates quickly - and who needs Grandma when we have schools and Wikipedia?

We might hope we're long past the days when levels of respect for old people unconsciously tracked some balance of costs and benefits. Still, if we believe a dignified old age is a right, perhaps we should be saying that, as clearly and as often as possible.

The author writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published13 November 2017

- Published5 December 2019

- Published11 July 2019

- Published24 May 2019