The little lights now packing a deadly punch

- Published

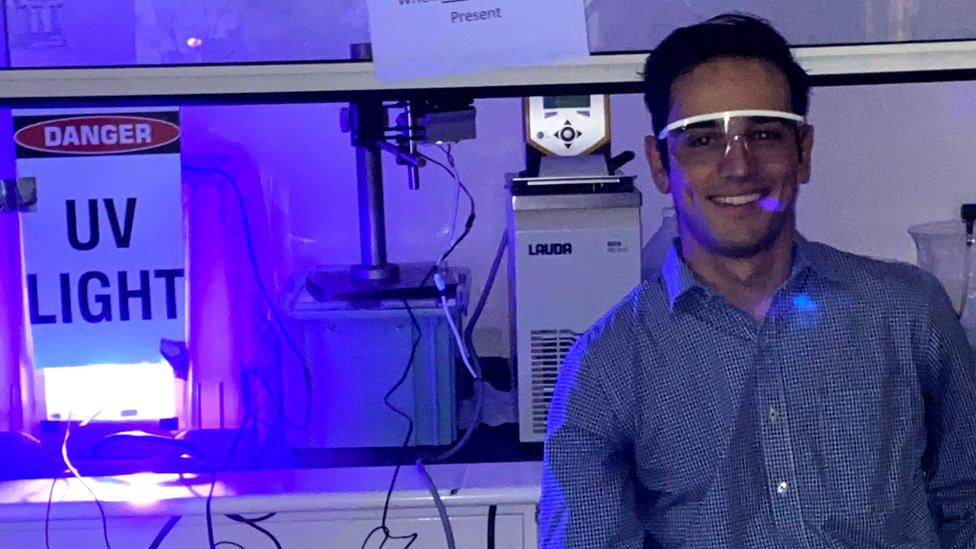

Christian Zollner has been trying to find new uses for LEDs

"The tech we are working on could transform water sanitisation techniques and offer access to clean drinking water to even remote developing regions via portable systems," says Christian Zollner from the University of California in Santa Barbara.

Mr Zollner has been working on light emitting diodes (LEDs), the long-lasting technology in modern lightbulbs. They are probably in the lightbulbs in your house, or the headlamps of your car.

Because they are tough and energy efficient, researchers are always trying to find new ways of using them.

Mr Zollner and his team have been working on LEDs that emit ultraviolet light, in particular UV-C light, which is deadly to bacteria and viruses, including the coronavirus.

His goal is to make those LEDs more powerful, robust and cheaper.

"Right now, UV LEDs are capable of a few milliwatts of power. Our aim is to make them 10 to 20 times more powerful.

"Our focus previously was mainly on using them for water sterilisation, but the Covid-19 pandemic has made us realise there is also a big market for sanitising surfaces and equipment. If there is another virus situation in say five or 10 years, this technology could be very useful."

At the moment his lights are powerful enough to cleanse a closed cabinet, but need to be 20 times more powerful to zap a whole room.

The light can also damage human skin and eyes, so the commercial applications are limited.

But one firm has found a use. Californian firm LARQ makes what it says is the world's first self-cleaning water bottle.

Its solution to prevent exposure to UV-C light is to ensure the tiny UV LEDs in the lids of its bottles only come on when the bottles are screwed shut.

Users must then push down on the lid to activate the technology, which the company claims eradicates more or less all bacteria and viruses in 60 seconds.

It might look like an ordinary bottle, but it can zap viruses

LEDs have come a long way since the first were produced in the 1960s.

Back then, the only light the semiconductor devices could generate was an infrared light invisible to the human eye.

Now, they cover the entire visible spectrum, as well as infrared and UV light and come in a dazzling array of forms.

Micro-LEDs that measure less than 1mm across are another of the latest variants.

Designed for use in high-end screens, micro-LEDs promise blacker blacks, brighter blues.

Samsung's giant new screen uses micro-LED technology

Samsung has been showing off its massive screen, external made of micro-LEDs at consumer electronics shows.

"Micro-LED display technology offers a huge improvement to standard LED panels due to its optimum brightness and image definition," says Damon Crowhurst, head of display at Samsung UK.

But the engineering involved is mind-boggling. The screens need millions of micro-LEDs, which means they are expensive - a 75-inch TV costs tens of thousands of pounds.

"Micro-LED screens cost about £1,000 per inch to make, so a 75-inch micro-LED television could easily cost the same as a new Porsche Cayenne," says Paul Gray, an analyst at global technology researcher Omdia.

"You have to ask yourself how many people will be prepared to pay that to get better contrast when they watch TV."

The crushingly high cost of micro-LEDs is one reason a number of manufacturers currently prefer mini-LEDs, which though still tiny measure more than 1mm across.

Apple, for example, is rumoured to be developing six new products with mini-LED displays, including both iPads and MacBooks.

In the short term, small-screen devices such as smartwatches are expected to be the biggest growth area for micro-LEDs.

"Small screens are a much easier proposition, as a 1cm micro-LED screen can be made on a single silicon chip," Mr Gray says.

"They are already being used in camera viewfinders. So for products such as smartwatches, we are looking at a much shorter timeframe."

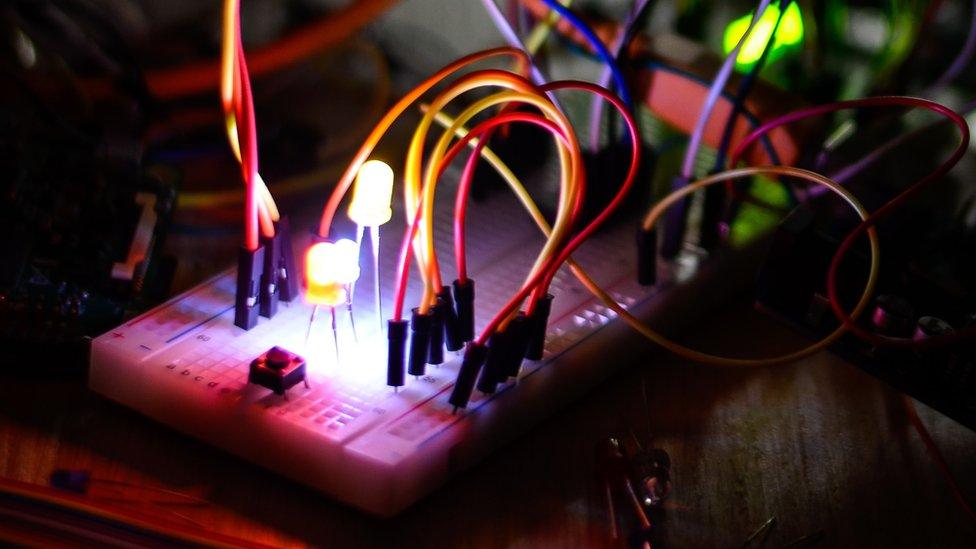

Researchers are trying to make LEDs more efficient

Researchers are finding ever more exotic ways to make the perfect LED - more light with less power.

UK-based start-up Kubos Semiconductors is developing LEDs based on a form of Gallium Nitride (GaN) with a crystal structure that is cubic rather than hexagonal, an approach it believes could solve long-term problems creating more efficient micro-LEDs.

At the moment, green and amber LEDs are up to three times less efficient than blue and red ones.

Known as the Green Gap, the phenomenon reduces the performance and increases the cost of lighting and displays.

"This will be very important in applications such as mobile phones and smartwatches where displays need to run off a battery," says Kubos chief executive Caroline O'Brien.

Elsewhere, researchers are working to reduce LED production costs and environmental impact.

An EU-funded study is experimenting with using naturally occurring fluorescent protein structures to create bio-LEDs.

Based in Austria, Spain, and Italy, the multi-university project began in January and is due to run for four years.

"The goal is to find a cheaper and more environmentally friendly way of producing LEDs by avoiding the need for inorganic phosphates that have to be mined in specific locations," says Gustav Oberdorfer, who is leading research at Graz University of Technology in Austria.

"We hope our LEDs will be used commercially in devices within the next 10 years, and believe they could both lower the cost of LED devices and make them much more sustainable."

So next time you turn on a light, think of the humble LED, which has come a long way since the 1960s and has a bright future.