Get ready for the 'holy grail' of computer graphics

- Published

Jason Ronald from Xbox

Ray tracing has always been the "holy grail" of computer graphics, says Jason Ronald, head of program management for the gaming console Xbox.

The technique simulates a three-dimensional image by calculating each ray of light and promises stunning lighting effects with realistic reflections and shadows.

The method finds where it bounces, collects information about what those objects are, then uses it to lay down a pixel and compose a scene.

While the techniques have been around for a long time, "we just haven't had processing power to deliver all of that in real time", Mr Ronald says.

In Hollywood, special effects have used ray tracing for a decade. For an important sequence, computers could churn overnight for a single frame.

To do this for games in real time, you need to condense that to 1/60th of a second. Processing speed has now caught up to the task.

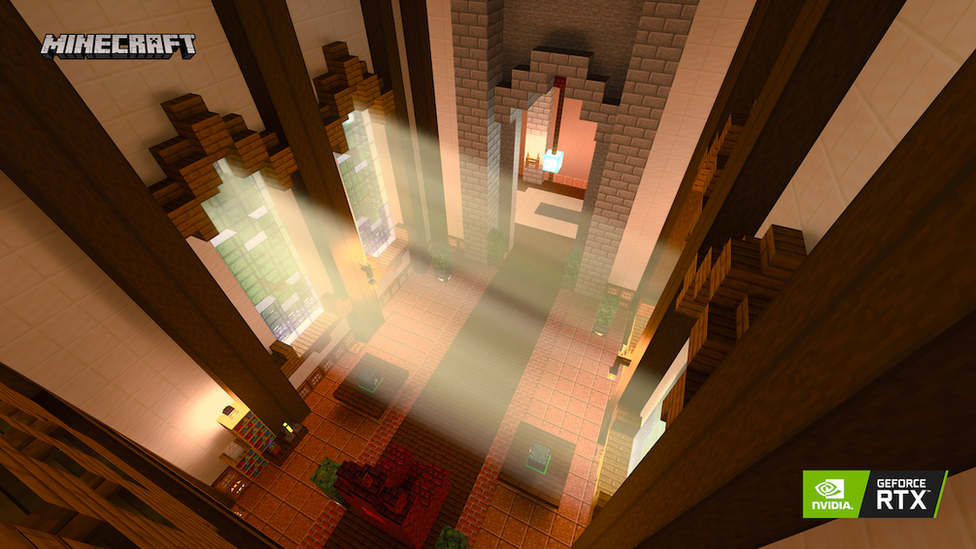

Ray tracing creates more realistic light and shadows

Tech company Nvidia announced last year their latest graphics processing units (GPUs) will handle real-time ray tracing.

Working with Nvidia, Microsoft developed a ray tracing update to Windows 10.

Microsoft and Sony have announced their upcoming consoles, the Xbox Series X and the PlayStation 5, will have ray tracing capabilities. Both of these systems are built on Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) hardware.

And now the tech is being incorporated into some of the world's most popular games.

Minecraft, which first appeared in 2009, allows players to construct vast intricate structures. Developed by Swedish game studio Mojang, it currently is the best-selling video game in history.

Minecraft's makers released an early ray-tracing version of their game on 16 April. A general release will follow near the end of the year.

"It looks very different from the traditional rendering mode, and it looks better," says Jarred Walton, hardware editor at PC Gamer.

The big problem, he says, will be price barriers for now. "The only way you can play it is with a PC that has a graphics card that costs at least $300 (£240)," he says.

Ray tracing requires expensive processor chips

Until now, developers used another technique called rasterisation.

It first appeared in the mid-1990s, is extremely quick, and represents 3D shapes in triangles and polygons. The one nearest the viewer determines the pixel.

Then, programmers have to employ tricks to simulate what lighting looks like. That includes lightmaps, which calculate the brightness of surfaces ahead of time, says Mr Ronald.

But these hacks have limitations. They're static, so fall apart when you move around. For example you might zoom in on a mirror and find that your reflection has disappeared.

Programmable shaders started appearing around 2001. They did a much better job at 3D lighting tasks but required much more computational power.

"If we put all that into one game, the most amazing processor in the world would've gone just no, it's too much," says Ben Archard, senior rendering programmer at Malta-based 4A Games, developers behind a 2019 post-apocalyptic game called Metro Exodus.

There were ways around that. If a programmer wanted to simulate the hazy light coming through fog, instead of working out all the points, they could just calculate a sample of them. (These are called stochastic, statistical, or Monte Carlo approaches.)

Underwater scenes are Kasia Swica's favourite use of ray tracing

But with these workarounds, "pretty quickly you lose that realism in a scene," observes Kasia Swica, Minecraft's senior program manager, based in Seattle.

Ray tracing does better with realistic, real-time shadows, or reflections lurking in water or glass.

"My favourite thing to do with ray tracing is to go underwater," says Miss Swica.

"You get really realistic reflections and refractions, and neat shafts of light coming through as well," she says.

With lockdowns around the world due to the coronavirus pandemic, the need for people to feel close while isolated "is going to accelerate" progress in technology, says Rev Lebaredian, vice president for simulation technology at Nvidia, in San Francisco.

"With virtual and augmented reality, we're starting to feel like we're in the same place together," he says.

So coronavirus will drive demand and progress, agrees Frank Azor, chief gaming solutions architect at AMD.

Impressive lighting is possible even without ray tracing

One "fiendish problem" for ray tracing has involved how shaders can call on other shaders if two rays interact, says Andrew Goossen, a technical fellow at Microsoft who works on the Xbox Series X.

GPUs work on problems like rays in parallel: making parallel processes talk to each other is complex.

Working out technical problems for improving ray tracing will be the main tasks "in the next five to seven years of computer graphics, at least," says Mr Ronald.

In the meantime games companies will use other techniques to make games look slicker.

Earlier this month Epic Games, the makers of Fortnite, released its latest game architecture, the Unreal Engine 5.

It uses a combination of techniques, including a library of objects that can be imported into games as hundreds of millions of polygons, and a hierarchy of details treating large and small objects differently to save on its demands on processor resources.

For most game makers such "hacks and tricks" will be good enough, says Mr Walton.