Coronavirus: What's it like to be laid off over Zoom?

- Published

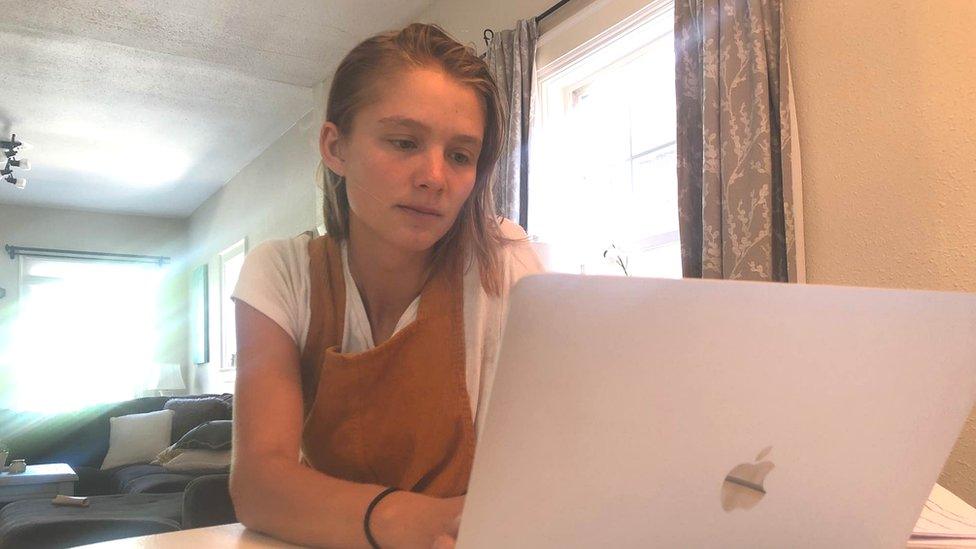

Ruthie Townsend found her firm's redundancy process upsetting

When travel start-up Pana held a meeting for all of its employees over Zoom, they explained that some staff would be laid off, and that there would be two further calls that morning - one at 09:00 for those who would be laid off, and one at 09:45 for those who would not.

Employees would know which meeting they were attending by the invites they would have received by email.

Sales executive Ruthie Townsend was invited to join the 09:00 call but, due to the shock of the news, she could not remember which call was for those about to be laid off, and which was for those being retained.

"Because it was such a highly stressful situation, it was hard to process what was going on so I got mixed up. I joined the 09:00 call as that was the invite I had, and once I realised that I was being laid off, I quickly turned off my video," she says.

Ms Townsend was on the call with 15 of her colleagues, and executives from the company then walked these employees through the benefits, the severance package and the next steps.

Ruthie Townsend worked for a travel firm

The company, based in Denver, Colorado, had been hit by the collapse in travel due to the coronavirus outbreak.

But there had been a feeling that redundancies would be a last resort, and Ms Townsend had no idea what was coming that morning.

That kind of shock is unfortunately commonplace at the moment, as companies are slashing staff numbers to cope with the economic fallout from the coronavirus.

Before the crisis managers would usually have met staff face-to-face, to give them the bad news.

Now video-conferencing tools, such as Zoom and Microsoft Teams (MS Teams), are being used to replicate the formality of the meeting.

Chris Malone, an audio visual technician at events company Sparq in the UK, feared for his role when it was explained to him that a HR representative would be on his next MS Teams call along with his line manager.

His instincts proved correct, as he was told he was going to be laid off.

For him, the use of a video call made the meeting formal, but more awkward than an in-person meeting or telephone call.

Chris found his video meeting "awkward"

"I think if you were doing it over the phone, it would mean you don't have to look at someone but when you have the video call, you get dressed up to make it feel formal and to look presentable.

"Even though it is a video call, the pressure is there - and as you're not in the room with them there isn't a natural chemistry, connection or body language you can read off, and there's a little bit of a delay, you're waiting for someone else to say something," he says.

However, Mr Malone believes that a one-to-one video call is still the best way a business can break the unfortunate news to an employee in the current circumstances.

For Ms Townsend, there were pros and cons to having more than 15 people on the same call as her.

"I don't think any way of making someone redundant over video conference is going to be ideal. If it's one-on-one, it's still going to be really hard and then your boss is going to see all of your emotions. I liked the group setting because I turned off my video, and I didn't have to say anything," she says.

However, she believes that the group setting prevented her from asking important questions at the time.

Sarah Evans, partner at law firm JMW, explains that communication prior to any announcement is key for employers.

"What many big businesses can do is conduct large meetings on Zoom, to make an announcement to the same people at the same time, so there's no miscommunication going around," she says.

This would make it clear that redundancies or the furlough scheme are being considered for employees, and would also make clear what this means for the business, and how they intend to follow-up with individuals.

Firing staff over a group call would not be allowed under UK law

It is key for employers to provide employees with time to absorb the information, ask questions and give people the opportunity to voluntarily be made redundant or furloughed.

"In redundancy cases, that would be at least a couple of meetings to go through opportunities to avoid redundancy and consider alternatives, and there's no reason why all of this can't be done on Zoom," she says.

The use of video, phone call or in-person, is not a legal matter; it's merely a matter of etiquette.

However, the group call, which Ruthie Townsend had experienced in the US, would not be allowed in the UK.

"That wouldn't cut it in UK law, as you have a right to individual consultation. There's nothing wrong with a group call to announce potential redundancies but you shouldn't be making people redundant in the same video call," Ms Evans says.

If this were the way a UK employer had acted, the employee might then have a case for unfair dismissal.

Recording video calls can create legal issues says Peter Binning

The option to record video calls could also prove problematic in these cases.

Peter Binning, a partner at law firm Corker Binning, explains that, generally speaking, anyone should ask for consent before recording a call of any kind.

However, regardless of whether consent was asked for, given or not given, a recorded conversation could still be admissible in an unfair dismissal case.

"Whoever wants to use the evidence has to be able to prove that it had been properly recorded and was genuine but it would be a matter for the court or tribunal to decide whether that evidence should be admitted," Mr Binning says.

And those wanting to snoop on people by deliberately joining a Zoom call where someone else is being made redundant would most definitely be breaking the law - as there are a number of criminal offences about intercepting communications in the regulations.

While video may create new problems, it is the best replacement for a meeting in person.

"It will feel more uncomfortable to look someone in the eye, and the level of emotional frustration and anger will be more visible, but it is essential to delivering the message in an open, fair and transparent way to another person," says Stuart Duff, an expert on the psychology of leadership at business psychology consultancy Pearn Kandola.