'It's your device, you should be able to repair it'

- Published

Suhaib started fixing phones at school

What would you do if your smartphone was damaged or stopped working? Take it to a repair shop or perhaps upgrade to a new one?

Not Suhaib. Unable to afford the repair cost he ordered a replacement screen, watched an online tutorial and fixed it himself.

"It took me around two hours. I was really nervous," says Suhaib (he prefers to keep his surname private).

It wasn't long before he became the person to go to at his Canadian school if you had a broken phone. "I was the guy fixing phones in class," he says.

Suhaib and other like-minded repairers are trying to help reduce the vast amount of electronic goods discarded every year.

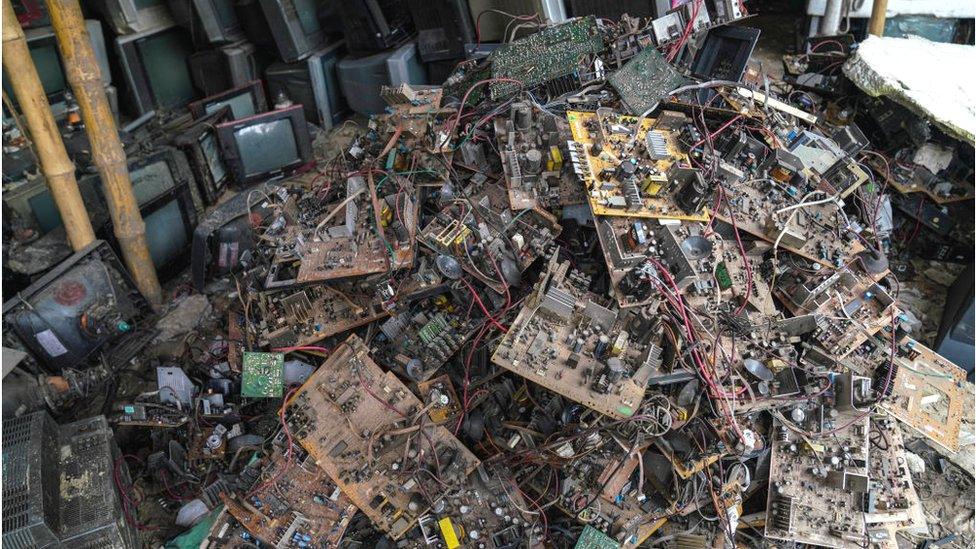

A record 53.6 million tonnes of electronic waste was generated worldwide in 2019, with less than a fifth of it being recycled, according to the UN's Global E-waste Monitor 2020.

By 2030, the report predicts global e-waste will reach 74 million tonnes.

Millions of tonnes of electronic waste are dumped every year

"E-waste is the world's fastest growing waste stream," says Rolf Skar, special projects manager at Greenpeace USA.

"By not recycling the precious metals we've already mined, companies now need to rely on destructive mining practices that scar the Earth permanently."

The European Environmental Bureau (EEB) says extending the life of smartphones and other electronics by just one year would be the equivalent of taking two million cars off the road,, external in terms of CO2 emissions.

Suhaib is one of the growing number of people mending their own devices and teaching others to do the same. He runs a YouTube channel called Phone Repair Guru where he posts tutorials of his repairs.

He is trying to tackle the understandable reluctance many of us have when it comes to opening up our faulty phones.

"I think me doing that has enabled people to have less fear when opening their device," he explains.

"It's your device, you should be able to repair it, there shouldn't really be anything stopping you."

Fridges, washing machines and TVs should last longer and be cheaper to run under new EU rules that will be introduced in the summer.

"The goal is to ensure that sustainable products become the norm," EU Environment Commissioner, Virginijus Sinkevičius, told BBC News.

"Reparability is a key element of striving for high-quality products that last."

Although the changes are being billed as a "right to repair" law, campaigners say more needs to be done.

"We can [now] say we have reparability requirements in Europe, but we can't say we have the right to repair," says Chloé Mikolajczak from Right to Repair Europe.

The law doesn't yet cover smartphones and tablets that she says are getting harder to fix. One problem is keeping older devices updated with new software.

But she hopes that some repair requirements for such devices will be introduced by 2023.

In its defence, the electronics industry says it is making products repairable - up to a point.

"We believe European consumers should have access to a high-quality, safe and secure repair option in all cases," says Cecilia Bonefeld-Dahl, director general of European electronics industry body DigitalEurope.

"However, given the high complexity of ICT (information and communications technology) products, it will not always be possible for consumers to carry out repairs safely and successfully.

"When designing the 'right to repair', it will be important to consider how to ensure quality and consumer safety, security and privacy as well as recognise the importance of manufacturer-led repair networks," she says.

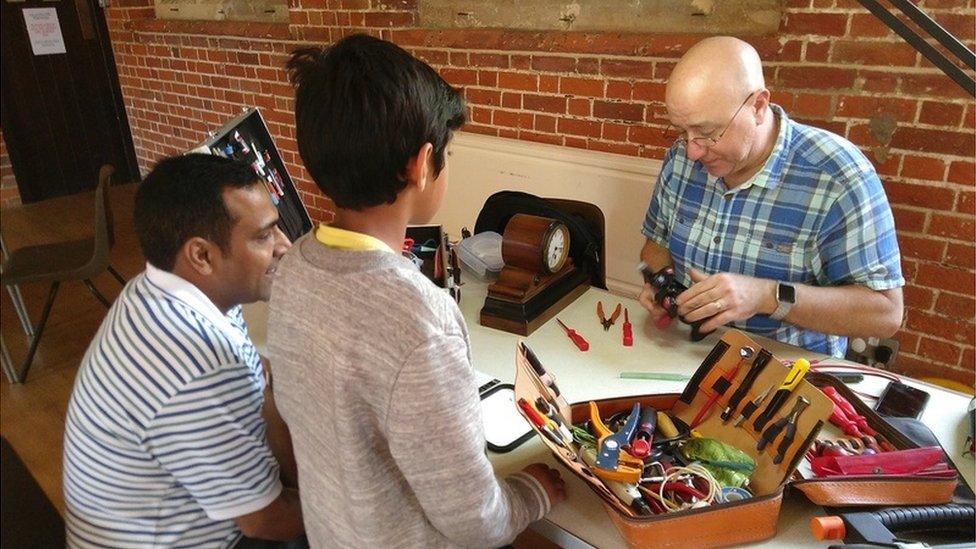

The Marlow Repair Café

In the meantime, repair cafés are doing the best they can.

Pioneered by journalist Martine Postma in Amsterdam in 2009, hundreds of similar cafés now exist across the globe.

One of these was set up in the UK by Frank Schoofs, who runs the Marlow Repair Café.

"[It was born out of] the frustration of having something that breaks and finding out you actually don't have the right tools, spare parts or manual."

Frank says he brought together volunteers "who still know how to repair things with people who have things that are broken and don't know how to repair them".

The café now runs events in church halls and libraries, and repairs are free.

The products that typically turn up include toasters, radios, clocks, kettles, smartphones, toys, watches and even at one point a large freezer.

"There's a social and community-building aspect to [repair cafés]," he says.

The Repair Café Bengaluru team has organised 45 workshops across the city

It's the community aspect that led Purna Sarkar to start the Repair Café Bengaluru, although the reasons for a repair culture in India are very different.

"In India, repair is not costly," she explains. "It is more pertinent to speak about right to livelihood for repairers."

She says "frugality" is deeply embedded in Indian culture. For generations repairers provided a valuable service helping to extend the life of domestic objects.

But markets have now become flooded with products that are less repairable.

Repair Café Bengaluru has arranged more than 45 workshops across the city with the help of around 15 volunteers. It also organises events at schools, hospitals, colleges and clubs.

Club de Reparadores founders, left to right: Melina Scioli, Marina Pla and Julieta Morosoli

In Argentina, Melina Scioli, Marina Pla, Julieta Morosoli and Camila Naveira run the Club de Reparadores in Buenos Aires.

"The ability to hack, improvise and creatively solve problems - which is key to repairing - is very much part of our local idiosyncrasy," says Melina.

Argentina's prolonged economic crisis has also often meant that imports of certain goods and spare parts have been halted.

"This probably has contributed to the local talent to reuse, repurpose, fix, and find ways around repair," says Melina.

Club de Reparadores is run as a non-profit project that promotes the organisation of independently run repair events around the country and in Latin America.

Argentina has a strong "repair culture"

"People of all ages and occupations come to share skills, knowledge and tools in order to extend the lifespan of objects... promoting collaboration among peers, a greater sense of ownership and empowerment, and a more critical consumer culture," Melina says.

Despite these successes, campaigners say only stricter regulations will really allow more of our household gadgets to be repaired.

Ugo Vallauri of the social enterprise, the Restart Project, says a systematic change is needed.

"It requires laws in place that prevent manufacturers from stopping [supporting] a product too early, or making it pretty much impossible to repair it by design."