How farmers and scientists are engineering your food

- Published

Franco Fubini, founder of fruit and vegetable supplier Natoora

"Flavour is a re-emerging trend, without a doubt," says Franco Fubini, founder of fruit and vegetable supplier Natoora.

You might be surprised that flavour ever went out of fashion.

But finding truly tasty fruit and vegetable varieties can be difficult, largely due to the requirements of supermarkets, he says.

"They started demanding that varieties have a longer shelf life, so for example in the case of a tomato, it has a thicker skin, so the skins don't split more easily; a tomato that perhaps ripens faster, that can absorb more water.

"So over time you breed your varieties for attributes other than flavour. The flavour attribute starts falling in importance, and as nature has it, if you breed for other traits you breed out flavour."

Mr Fubini's company specialises in seasonal produce selected for flavour, and sells its produce to restaurants and high-end shops around the world.

"Some of this rebirth comes from restaurants because chefs have quite a lot of influence," he says. "That and travel have both spurred on this rebirth of flavour, this search for flavour."

Breeders and researchers are leading this search, using sophisticated techniques to produce fruit and vegetables that have all the flavour of traditional varieties - while still keeping the supermarkets happy.

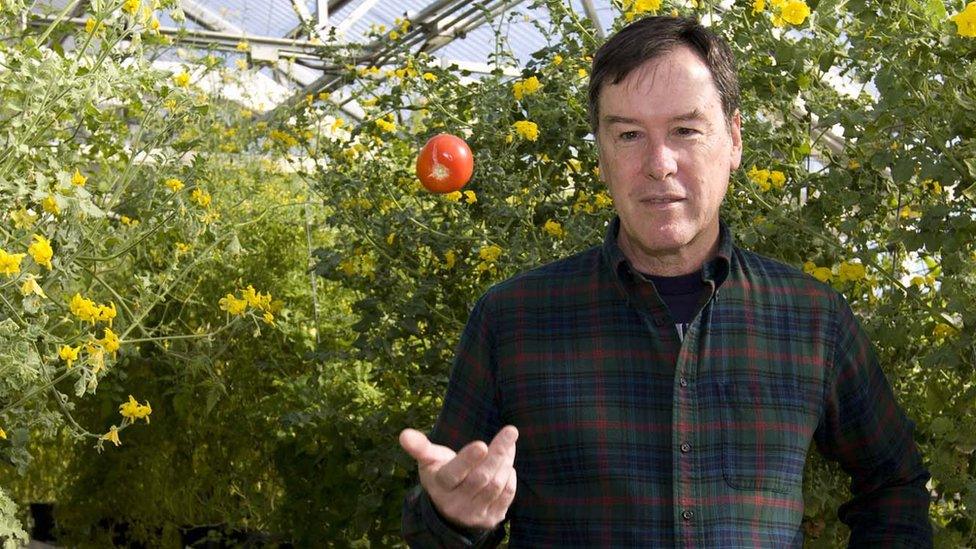

Harry Klee uses the tomato to understand the chemical and genetic make-up of fruit and vegetables

Prof Harry Klee of Florida University's horticultural sciences department is working to understand the chemical and genetic make-up of fruit and vegetable flavours - focusing on the tomato.

"The tomato has been a long-term model system for fruit development. It has a short generation time, great genetic resources and [is] the most economically important fruit crop worldwide.

"It was only the second plant species to get a complete genome sequence - a huge help in studying the genetics of an organism."

Plant flavour is a complex phenomenon. In the case of a tomato, it stems from the interaction of sugars, acids and over a dozen volatile compounds derived from amino acids, fatty acids and carotenoids.

Prof Klee wants to identify the genes controlling the synthesis of the flavour volatiles, and using this to produce a better-tasting tomato.

"It's not quite at the stage where we have completed assembling the superior flavour traits into a single line, but we expect to be there in another year or so," he says.

It is possible to use genetic modification (GM) to improve flavour by importing genes from other species, but in much of the world produce created this way is banned.

Pairwise is using gene editing technology to create new varieties of crops like raspberries

However, other forms of genetic manipulation are more widely accepted. US firm Pairwise is working on new fruit and vegetable varieties by using CRISPR - gene editing technology licensed from Harvard, the Broad Institute and Massachusetts General Hospital.

Rather than taking genes from other species, like GM, CRISPR involves tweaking existing genes within the plant by cutting and splicing.

"We're making very small changes in one or two pieces of DNA," says Pairwise co-founder Haven Baker.

Such gene editing is considered "non-GM" in most of North America, South America and Japan. However in Europe, where genetic modification is highly contentious, it is considered GM and is kept under strict regulation.

Having left the EU, the UK has launched a consultation on using gene editing, external to modify livestock and food crops in England.

Even in the US, where views are less entrenched, some growers are wary of genetic modification.

"We are not fans of it at all. While sometimes innovation done right maybe does work well, we believe in tradition and not necessarily messing with things - and going back to nature and the way nature functions," says Mr Fubini.

But some innovation would be extremely difficult without intervention at the genetic level.

One of Pairwise's first products, expected in a year or two, will be a seedless blackberry it says will have a more consistent taste than traditional varieties. It is also working on a stoneless cherry.

All this could be done through traditional breeding techniques, but as fruit trees take years to mature it would be a very long-term project.

"Some of the fruits we're interested in, like cherries where we want a pitless cherry, theoretically you could do it with breeding but it would take 100-150 years," says Mr Baker.

"The products we want to make and we think consumers want are not achievable in our lifetimes with conventional breeding, it's just too slow."

Seed supplier Row 7 has 150 cooks and chefs giving it feedback on crops like its Badger Flame beet

Some in the agriculture business are combining old and new techniques. US-based organic seed firm Row 7, runs breeding programmes to develop new and better tasting produce.

Its seed suppliers use traditional cross-pollination techniques, along with genomic selection - the ability to examine molecular genetic markers across the plant's whole genome - to predict traits such as flavour with reasonable accuracy.

In addition, it has a network of 150 chefs and farmers that evaluate its work.

"This community evaluates varieties that are still in development, providing feedback on their potential in the field and in the kitchen," says chief operating officer Charlotte Douglas.

One of its flagship products is Badger Flame beet; bred to be eaten raw and sweet without being earthy.

"This variety would have gotten lost, were it not for the advocacy of chefs and growers. It's expanding our understanding of what a beet can be, introducing new opportunities for exploration," says Ms Douglas.

Kale's strong taste is too much for some: we could soon see kale that tastes like lettuce

Some plants might be lumbered with the wrong kind of flavour. Take kale, for example, although the leafy green is nutritious, its powerful flavour can be off-putting.

Mr Baker and his team at Pairwise, are working on a sweeter and gentler plant.

"Kale is very nutritious, but people don't like to eat it. So we've used genetic engineering to produce leafy greens that have better nutrition, but that taste like the lettuces we're used to," he says.

In the case of kale, strong flavour is seen as a disadvantage, but generally speaking flavour tends to go hand-in-hand with nutrition.

"Breeding for flavour means breeding for deliciousness; it means breeding for nutrition because more often than not when you are selecting for complex flavour you're also selecting for nutrient density," says Ms Douglas.

"It means breeding in and for organic systems - the type of farming that produce the best possible tasting plants; it means breeding for more diversity."