Smart headbands claim to make people calmer. Do they work?

- Published

Emma Baumert says the FocusCalm headband helps her relax

Emma Baumert admits that when she first put on the high-tech headband she felt silly. "But I also felt so cool wearing it, because I'm such a nerd."

The 24-year-old from Illinois is a member of the USA Bobsled/Skeleton development team.

An all-round athlete, she is also a qualified weightlifting coach, and this year gained a masters degree in exercise physiology.

The headband she now uses is a neurofeedback or EEG (electroencephalogram) device. Growing in popularity among sports people, they measure the wearer's brainwaves.

As a stressed brain gives off more waves or signals, due to increased electrical activity, the idea is, that, together with meditation, the headbands can help the user train him or herself to be calmer. And then in turn boost their performance.

But are such devices, which are otherwise used by doctors to test for conditions such as epilepsy and strokes,, external really beneficial in helping people to reduce their stress?

Ms Baumert says she wanted to find out after trying out a headset called FocusCalm two years ago. "After using it myself, I was like 'I want to do more research on this'," she says.

Emma Baumert aims to compete for the US in the Winter Olympics

So, she contacted the firm behind the product, Massachusetts-based BrainCo. Given her relevant university studies, and her weightlifting and winter sports participation, they invited her to become a part-time, but paid, researcher for a few months in 2020. and again earlier this year.

Ms Baumert is now convinced the device works. "I got to visualise and learn how to have better control, and what training I need to do to get into a more relaxed state, while still being able to have very high explosive power output."

New Tech Economy is a series exploring how technological innovation is set to shape the new emerging economic landscape.

Max Newlon, president of BrainCo, explains that the headband uses an AI (artificial intelligence) software algorithm to monitor 1,250 "data points" in a person's brainwave signals. Connected to a mobile phone app, it then scores them on a scale of 0 to 100, with 100 being calmest.

Most of the time the average person apparently hovers around the 50 mark.

"It's a passive measure, there's nothing going into your brain," says Mr Newlon, who first started working on the technology in 2015. "We have people doing all different types of experiments, like spending time with their family... to learn about themselves and discover what puts them in that focused and calm state."

Like physical exercise making the body stronger, Mr Newlon says that people can learn to relax their brain, and that once the skill is acquired, it sticks.

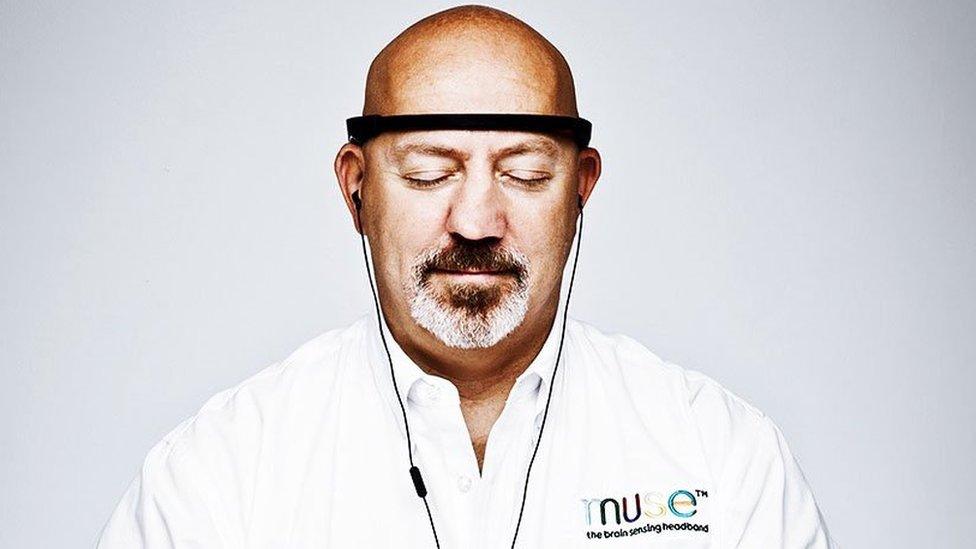

Another EEG headband developer, Canadian firm InteraXon, created its product - the Muse - in 2014.

The Muse headband also measures aspects of a person's sleep

It is also designed to help make you feel calmer, and in turn support meditation or better sleep.

In addition to measuring brainwaves it records heart rate, speed of breathing, and a person's posture. And it comes with an app that plays soothing sounds, such as that of a rainforest.

Derek Luke, chief executive of InteraXon, says its customers are either "trying to address an issue in their life", such as stress and anxiety, or "proactively trying to improve" at something, such as their performance in a certain sport.

This all sounds good, yet Dr Naomi Murphy, a UK clinical and forensic psychologist, is cautious of consumer EEG devices.

The headbands encourage people to work towards "norms" for an average brain, she says. "This can leave some people feeling over or under stimulated after using them - perhaps because their brains don't quite fit the 'average' brain," she adds.

"Whilst some people find measurements useful or reinforcing, many are attracted to 'neuro-tech' because they identify with a vulnerability, an anxiety about their performance, and the use of data can exacerbate this."

Derek Luke says that sportsmen and women use Muse to help boost their performance

Meanwhile, Prof Sandra Wachter of Oxford University, a leading artificial intelligence expert, questions whether EEG devices aimed at making people less stressed should ever be needed.

"Mindfulness training and meditation might be one of the areas where I see very little room that AI can improve traditional ways of practising," she says, citing Buddhist and Hindu methods as superior.

Measuring one's mindfulness against an average, misses the point, she says which is "to only listen to yourself."

"In addition, there is no such thing as 'ideal relaxation' or 'problematic stress levels scores' because every person is different."

Both the Muse (pictured) and FocusCalm are increasingly used by sports players

However, Dr Steve Allder, a UK consultant neurologist, is supportive of consumer EEG devices, especially when they are used by athletes.

"Having any mind practice is likely to provide a performance advantage," he says. "And using a tool that provides physiological feedback into the practice is likely to improve the depth of an individual's 'mind' control, so tools with 'neuro-feedback' are helpful.

"The holy grail of elite athletes is to consistently access the 'zone'. This type of practice will increase the chance of that."

Back in the US, Ms Baumert says that while the headbands are very helpful, athletes should not see them as a "magic trick".

"Take what you've learned, and then just put it right into practice," she says.