Bank of England expects UK to fall into longest ever recession

- Published

- comments

Mini-budget "damaged" the UK's reputation, says Bank of England boss

The Bank of England has warned the UK is facing its longest recession since records began, as it raised interest rates by the most in 33 years.

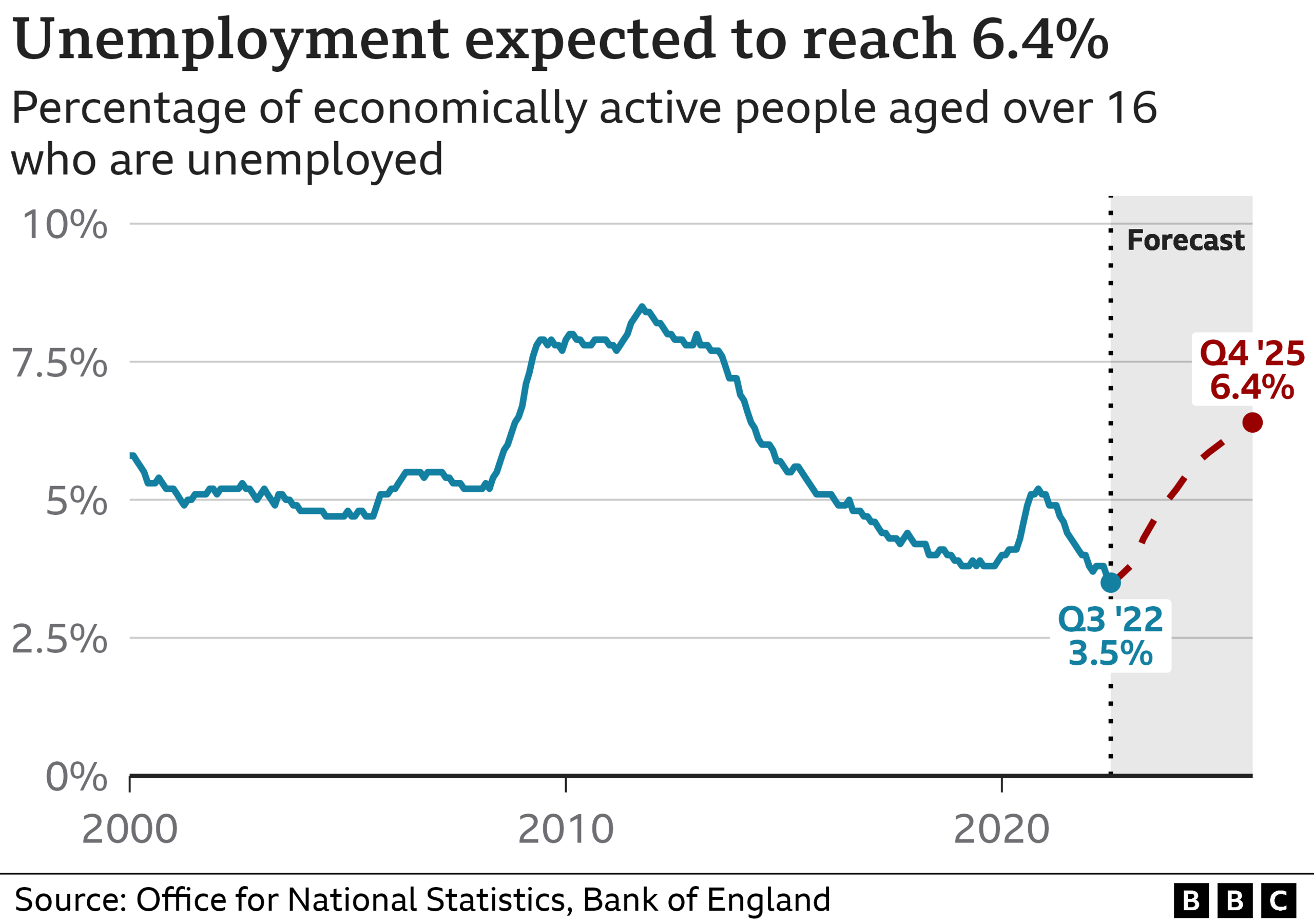

It warned the UK would face a "very challenging" two-year slump with unemployment nearly doubling by 2025.

Bank boss Andrew Bailey warned of a "tough road ahead" for UK households, but said it had to act forcefully now or things "will be worse later on".

It lifted interest rates to 3% from 2.25%, the biggest jump since 1989.

By raising rates, the Bank is trying to bring down soaring prices as the cost of living rises at the fastest rate in 40 years.

Food and energy prices have jumped, in part because of the Ukraine war, which has left many households facing hardship and started to drag on the economy.

A recession is defined as when a country's economy shrinks for two three-month periods - or quarters - in a row.

Typically, companies make less money, pay falls and unemployment rises. This means the government receives less money in tax to use on public services such as health and education.

The Bank had previously expected the UK to fall into recession at the end of this year and said it would last for all next year.

But it now believes the economy already entered a "challenging" downturn this summer, which will continue next year and into the first half of 2024 - a possible general election year.

While it will not be the UK's deepest downturn, it will be the longest since records began in the 1920s, the Bank said.

The unemployment rate is currently at its lowest for 50 years, but it is expected to rise to nearly 6.5%.

The interest rate announcement is the first since former Prime Minister Liz Truss and former Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng unveiled their controversial mini-Budget in September.

Their plans for £45bn worth of unfunded tax cuts - much of which have been reversed - sent the value of the pound tumbling and sparked market turmoil, forcing the Bank of England to step in to restore calm.

Mr Bailey told the BBC he believed that the mini-budget had "damaged" the UK's standing internationally.

He said that at a recent International Monetary Fund gathering in Washington "it was very apparent to me that the UK's position and the UK's standing had been damaged".

That same week, Mr Kwarteng was sacked as Chancellor.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt said: "The most important thing the British government can do right now is to restore stability, sort out our public finances, and get debt falling so that interest rate rises are kept as low as possible."

But shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves said families could not withstand such high rate rises "when we've got rising food prices, rising energy bills and now higher mortgage rates as well".

The latest rate hike - the Bank's eighth since December - takes borrowing costs to their highest since 2008, when the UK banking system faced collapse.

The Bank believes by raising interest rates it will make it more expensive to borrow and encourage people not to spend money, easing the pressure on prices in the process.

But while its latest rate rise will be welcomed by savers, it will have a knock-on effect on those with mortgages, credit card debt and bank loans.

'I'm nervous about the loan on my van'

Michelle, 58, from East Riding in Yorkshire has a loan on a van and is nervous about rising interest rates.

"My disposable income has gone down dramatically recently and I earn more than the amount to get benefits," she told the BBC. "They need to help the middle earners."

Michelle needs the van to get to work as there's no public transport near her. But if her loan repayment costs rise she fears she'll have to give up the vehicle.

"I can work from home, but like most places my place of work wants us back in the office at least three days a week and I've had to have talks with them about how I can afford that.

"It's a 60-mile round trip, it's expensive."

Those with mortgages are also feeling nervous. The Bank forecasts that if interest rates continue to rise, those whose fixed rate deals are coming to an end could see their annual payments soar by up to £3,000.

It said that it would increase interest rates if inflation remained high. Financial markets had been expecting rates to peak at 5.25% but the Bank does not expect them to rise this high.

The Bank's rate decision comes before the government unveils its tax and spending plans under new Prime Minister Rishi Sunak at the Autumn Statement on 17 November.

On Thursday, the pound slumped 2% against the dollar and the cost of government borrowing rose in response to the Bank's warnings.

The Bank has done something it doesn't normally do in the published minutes of its decisions - it has given guidance that seems to suggest a peak in interest rates of about 4.5% next autumn.

For those with a glass half-full - this is lower than the 6% assumed just a month ago in the post mini-budget market turmoil.

While government borrowing costs and the level of the pound has somewhat recovered after a series of U-turns since, mortgage markets and business loans are still showing some stress, adding to the prolonged hit to the economy.

The forecast predicts that the unemployment rate will rise, while household incomes will come down too.

It is a picture of a painful economic period, with the UK performing worse than the US and the Eurozone.

Indeed, what was forecast as a sharp energy recession just three months ago, is now a shallower, but more prolonged energy and mortgage shock.

Additional reporting from Emma Pengelly and Jessica Sherwood

Related topics

- Published3 November 2022

- Published3 November 2022

- Published10 May 2024

- Published3 November 2022