UK has no alternative to Bank interest rate rises to calm inflation - Hunt

- Published

- comments

The UK has "no alternative" but to hike interest rates in a bid to tackle rising prices, the chancellor has said.

Jeremy Hunt said inflation - the rate at which prices rise - was the "number one challenge we face".

He said the government would be "unstinting in our support" for the Bank of England "to do what it takes" to slow inflation.

Rising interest rates and mortgage costs weighed on UK economic growth in April.

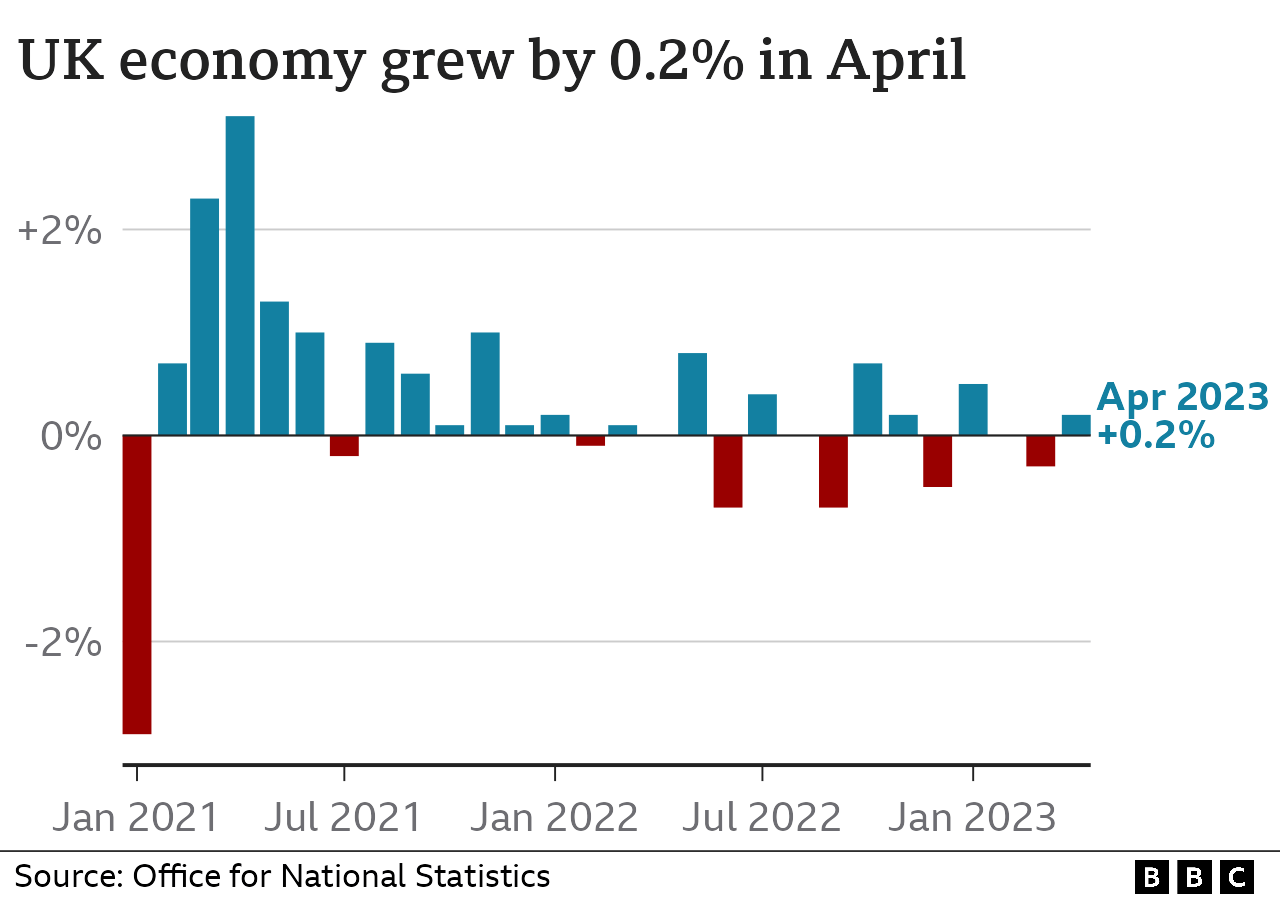

While the economy grew by 0.2%, the Office for National Statistics said that housebuilders and estate agents had a "poor month".

Borrowing costs have been steadily rising since December 2021 to a current 4.5% in an attempt to slow consumer price inflation, which stands at 8.7% - well above the Bank of England's 2% inflation target.

In theory, raising interest rates means it is more expensive for people to borrow and they have less money to spend. Consequently, they will buy fewer things which should slow the rate of rising prices.

An increase in interest rates means higher monthly mortgage, credit card and loan payments for some people. But higher rates should benefit savers - if banks pass them on to their customers.

Asked if he was following former chancellor John Major's dictum in 1989 that "if it isn't hurting, it isn't working", Mr Hunt said: "In the end there is no alternative to bringing down inflation, if we want to see consumers spending, if we want to see businesses investing, if we want to see long-term growth and prosperity."

The government has no say over interest rates since the Bank of England was granted independence in 1997.

The UK economy expanded in April after shrinking by 0.3% in the previous month. For the three months to April, it grew marginally by 0.1%.

The ONS said strong trade in bars and pubs boosted growth, but added the construction sector had faltered as rising interest rates and mortgage costs made house buyers more cautious.

As interest rates have risen and more people are coming to the end of fixed-rate mortgage deals, some lenders have been withdrawing certain mortgages from the market.

First-time buyers are being met with higher rates, leaving some priced out, and renters are also facing higher costs due to landlords selling up.

On Wednesday afternoon, HSBC, a major UK mortgage lender, temporarily withdrew new residential mortgages supplied through brokers.

"Over recent days cost of funds has increased and, like other banks, we have had to reflect that in our mortgage rates," an HSBC spokesperson said.

Hiking rates is meant to persuade consumers to spend less - as their cost of borrowing rises or rates on savings accounts increase - giving businesses less scope to raise prices.

But that mechanism may have become less effective over time.

Take mortgages. In the early 2000s, more than seven out of 10 residential mortgages were on variable or tracker rates, immediately impacted by rate hikes. Today, it's 15% of homeowners. Even adding in the 1.8 million who are re-mortgaging this year, means it's still, contrary to a couple of decades ago, the minority of mortgage holders who will be affected.

The impact of rate hikes is less widespread and may be taking longer to filter through.

Equally, banks and building societies have been particularly reluctant to pass on rate hikes to savers this time, as the Bank of England and outraged customers have noted. This may in part reflect savings institutions rebuilding margins after a period of ultra-low interest rates - but gives customers less of an incentive to stash spare cash.

Higher interest rates also should mean businesses have less scope to give workers inflation-matching pay rises than in the past - but a shortage of workers makes this less likely this time.

Even if, as some economists fear, interest rate rises are less effective this time, they remain the main tool for fighting inflation.

Ian Burns, who runs Cameron Homes, a housebuilder in Staffordshire, said people were being "very cautious" and were "taking longer to make decisions".

"Over the past three or four weeks, we've seen a slowdown in reservations," he told the BBC's Wake up to Money.

"We can't just continue to build houses if we don't have customers for them."

Stronger-than-expected wage growth for workers in the three months to April has raised the prospect that the Bank could raise rates close to 6% by the end of the year in its bid to reduce inflation.

On Monday, two-year government borrowing costs rose to levels higher than during the aftermath of last September's mini-budget.

When asked if this showed his plan was not working, Mr Hunt said: "We are in a very different situation to where we were last autumn. The IMF, the international commentators, think the British economy is on the right track."

But the New Economics Foundation, a think tank promoting social and economic justice, said the Bank should hold off on raising rates further and wait to see the impact of its previous increases.

Its economist Lukasz Krebel said that while UK wages were rising, they were still not keeping up with inflation, meaning people were poorer in real terms.

He added that rising prices were mainly due to supply side issues, such as worker shortages and Russia's invasion of Ukraine sending energy prices soaring.

"The UK government and the Bank should look to address underlying weaknesses that expose the UK to such inflation shocks - notably by supporting investment in clean energy and building retrofits to reduce our reliance on volatile fossil gas," he said.

Labour's shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves said the figures represented "another day in the dismal low growth record book of this Conservative government".

"The facts remain that families are feeling worse off, facing a soaring Tory mortgage penalty and we're lagging behind on the global stage."

Additional reporting by Raphael Sheridan

- Published13 June 2023

- Published13 June 2023

- Published11 May 2023