Oxford Rhodes statue row is part of global protest

- Published

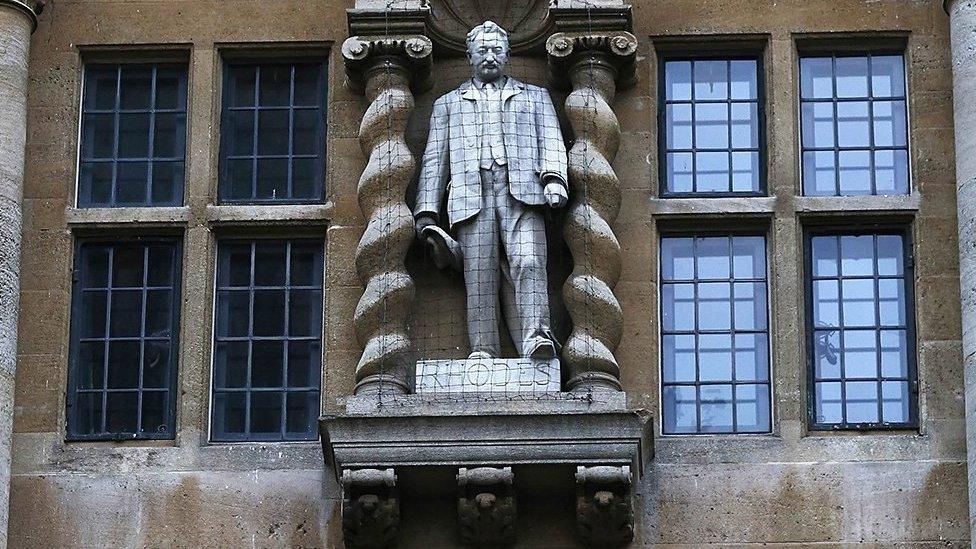

The Rhodes statue is going to remain on the front of Oriel College

How did a statue of a 19th Century politician on the front of a 14th Century college become such a 21st Century argument?

The decision by Oxford University's Oriel College to keep its statue of Cecil Rhodes was meant to draw a line under an angry dispute over emblems, cultural identity and how universities should deal with their own long histories.

Since the BBC website revealed in December that the college was consulting about whether to pull down the statue, there has been a constant bombardment of opinion, much of it aghast at the idea of "rewriting history" by getting rid of Rhodes and any uncomfortable links to a colonial past.

But don't expect the protest to disappear.

The Rhodes Must Fall campaigners attacked the college's announcement as "outrageous, dishonest and cynical" and promised to "redouble" their efforts.

Their indignation has been further inflamed by the college's promised six-month "listening exercise" over the fate of the statue not even making it to six weeks before it was prematurely ended with a statement put up on the college website, external on Thursday evening.

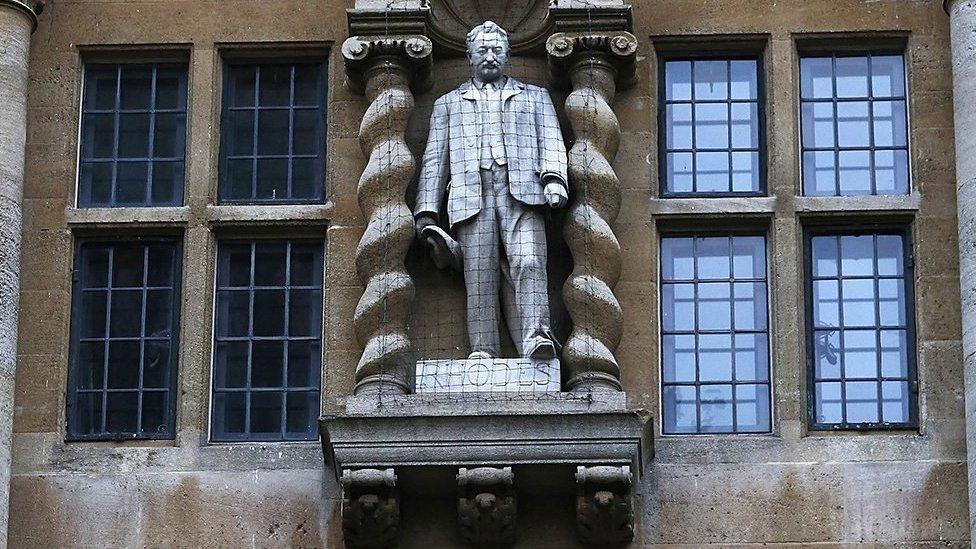

The statue of Cecil Rhodes has been taken away in Cape Town

There is another reason that such disputes will continue - and that's because they are part of a much bigger international student movement, fighting over symbols, statues and language.

And through social media many of these ideas are being enthusiastically shared between campaigners.

The Rhodes Must Fall campaign at Oxford follows the Rhodes Must Fall student campaign in South Africa, which saw a Rhodes statue in the University of Cape Town being dragged off its plinth as a symbol of the imperial past.

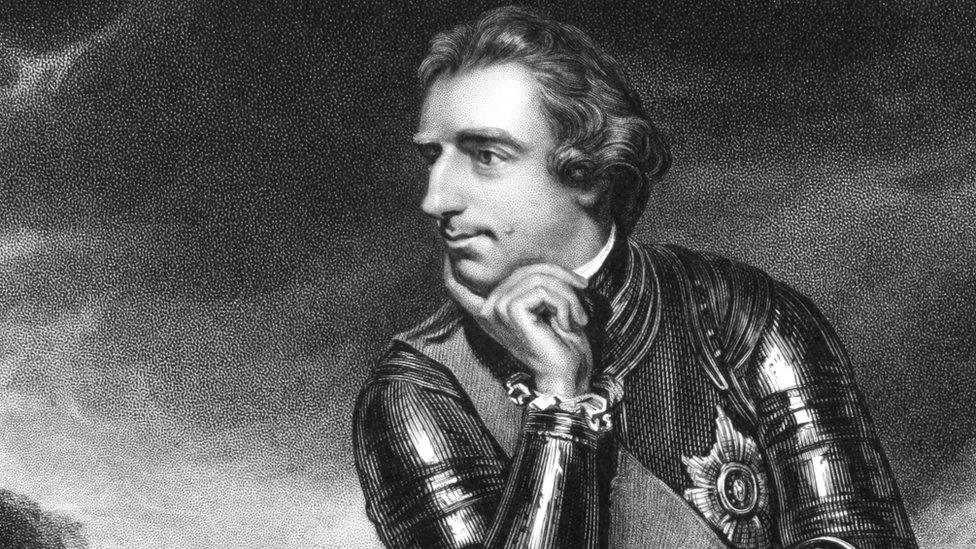

Why is Cecil Rhodes such a controversial figure?

But the biggest outbreak of culture wars has been in the US, where dozens of universities have been gripped by battles over symbols, race and identity.

And the student protesters are often winning.

In Harvard, the term "house master" for those running college houses has been ditched, because of connotations with slavery and "human subjugation".

There have been waves of protests over racism on US campuses

The university's law school is still weighing up a Royall Must Fall campaign, which wants to change the college's crest, which uses the coat of arms of the 18th Century Royall family who were notoriously brutal slave owners.

This week, Amherst College in Massachusetts accepted student demands and agreed to stop any links with Jeffery Amherst, an 18th Century general, accused of advocating deliberately infecting native Americans with smallpox.

Students had campaigned against the use of Lord Amherst as a symbol and unofficial mascot - and the college now says the campus hotel, the Lord Jeffery Inn, will also have to be renamed.

Earlier in this academic year, the president of the University of Missouri resigned amid student protests over the handling of racist incidents on campus.

These battles about race and identity - present and historic - have raged across campuses.

Amherst College has accepted student demands to remove any links to 18th Century general Lord Amherst

In Princeton, a school named after Woodrow Wilson has been the focus of protests and sit-ins, because of claims the former US president held entrenched racist views.

In Yale, there has been a campaign to rename Calhoun College, to remove links with John Calhoun, a 19th Century defender of slavery.

Fuelling the fire on these protests have been arguments over concepts such as "safe space" and "no platforming", where students have sought to prevent views or opinions that they deem offensive.

This has triggered furious arguments over free speech and the need for universities to be open to controversial views, even if they are uncomfortable, unpopular or even hateful.

Oxford's new vice-chancellor Louise Richardson says universities have to engage with uncomfortable ideas

The president of a university in Oklahoma thundered back: "This is not a day care, this is a university.", external And he accused students of becoming "self-absorbed and narcissistic" in their attitude towards any views they didn't share.

But these rows are showing no signs of stopping. They are a potent mix of identity politics, social media lobbying and consumer power.

In the UK, another dimension has been added by the government's drive against campus radicalisation, with bans on hate speech and extremist speakers - raising arguments about what is provocative and challenging and what is offensive and illegal.

Oxford is part of this global jigsaw. The university saw its new vice-chancellor, Louise Richardson, installed this month.

She argued in her inaugural speech that university needed to be intellectually stretching and meant students "engaging with ideas they find objectionable".

And statues too?

- Published29 January 2016

- Published20 January 2016

- Published17 December 2015