The men who had millions of lives in their hands

- Published

Foch and Haig meet again: Eric Becourt-Foch and Lord Astor remembered their military ancestors

In the commemorations of World War One there have been many stories from the descendants of those caught up in momentous and awful events.

These personal accounts, remembering the faces in grainy photographs and names on headstones, are usually of ordinary soldiers who fought in the trenches.

But a ceremony in London this week brought together descendants of two of the most iconic commanders from the war, the decision-makers whose orders sent millions into battle.

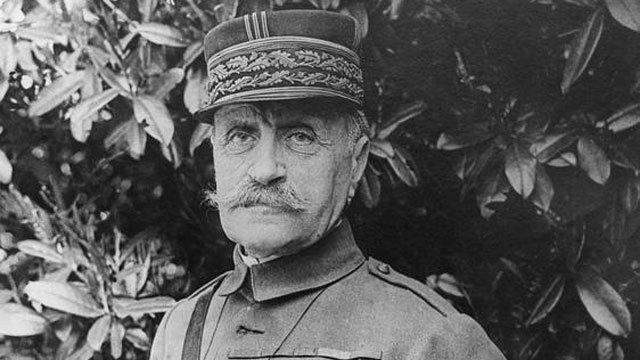

This latest war commemorations mark the point 100 years ago when a French marshal, Ferdinand Foch, was made supreme allied commander on the Western Front.

Haig and Foch worked together on the Western Front, with Foch appointed supreme commander in 1918

His great-grandson, Eric Becourt-Foch, was at the ceremony along with Lord Astor, grandson of one of most famous figures of the war, Field Marshal Douglas Haig.

The ancestors of these two men sent colossal armies into battle, with casualties on a scale not seen before or since. They literally had the fates of millions of lives in their hands.

Were they distant from the suffering of the front-line soldiers?

Mr Becourt-Foch said his great-grandfather had his "own share of sacrifice" and their family has never been sheltered from the loss of war.

Within the first month of the war his only son had died in battle. On the same day in August 1914, his son-in-law, Mr Becourt-Foch's grandfather, was also killed.

His grandson, Mr Becourt-Foch's father, fought and died with the Free French in North Africa in World War Two.

Eric Becourt-Foch said that his family had many wartime losses

"It cannot be a good thing. But we were attacked by the Germans, we had to defend ourselves," he said.

The ceremony in London was held at the statue of Marshal Foch near to Victoria Station - and marked the stage in the war in 1918 when the Western allies switched to a single, co-ordinated command to take on the Germans.

Mr Becourt-Foch says that when his great-grandfather went to receive the baton of field marshal from King George V, the conversation was in French. Foch, now in charge of British forces, spoke little English, but King George V was able to speak French.

They knew that the Germans would try to divide the allies, strategically and militarily, so Mr Becourt-Foch says his great-grandfather had to keep British and French forces together, "whatever it costs".

Marshal Foch spoke in French to King George V when he took over command

The connection continued after the war. Marshal Foch was a pall bearer at the funeral of Field Marshal Haig in 1928.

His grandson, Lord Astor, says there was a strong mutual respect between the two commanders. "He cried all the way through the funeral."

Haig's reputation has been under constant revision, following the historical cycle of being revered, reviled and then rehabilitated.

His name became associated with the terrible casualties of battles such as the Somme.

"I accept mistakes were made - but they learned from their mistakes and they built on them and we won the war in the end," said Lord Astor.

Lord Astor says his grandfather Lord Haig was "revered" in his lifetime by his soldiers

"We defeated the most powerful army in the world, the German army, and we should record that with pride.

"A lot of the focus has been on the problems - Passchendaele and the Somme - but we also should focus on the victories."

He defends his grandfather's approach to the war - as he commanded an army of two million men.

"He was accused of not being defensive enough, but what was the alternative - to sit in the trenches? You had to try and break out somewhere."

The posthumous criticism of Haig hurt his family.

"My mother was very affected - she was only eight when her father died - and she was shaken by some of the stories about him.

"But by the time she'd died, a lot of that had changed," he said.

Haig on the Western Front in 1916

Lord Astor says his grandfather was highly respected by his soldiers and later criticism failed to recognise how much he was admired at the time.

"He was revered in his lifetime. When he died, there were two million people on the streets of London."

The soldiers who had served under him lined the routes of his funeral, he says.

"They wouldn't have done that if he was unpopular," adds Lord Astor.

Eric Becourt-Foch in front of the statue to his great-grandfather

The ceremony in London marked the point when a common leadership was needed by the Western allies, with Foch's appointment backed by Haig.

Both Mr Becourt-Foch and Lord Astor emphasise the need to maintain the partnership between British and French military forces.

But now, says Mr Becourt-Foch, there is also "strong reconciliation" with Germany.

And while diplomatically stepping around the Brexit debate, he says the era after World War Two has helped to build "European unity".

French and British soldiers took part in a ceremony honouring Marshal Foch

The two families' names remain synonymous with World War One.

The Haig Fund used to be printed on remembrance poppies. In towns and villages across France there are thousands of streets named after Foch.

As the commemorations approach for the last stages of the war, Lord Astor says: "I think my main reason for remembering is for all the dead, there were very few families that didn't lose a member."

There are two more major commemorative events this year - marking the centenary of the Battle of Amiens and the armistice. Descendants of those who fought at Amiens can apply for tickets for a commemorative service, external in Amiens to be held on 8 August.

- Published22 January 2018

- Published15 December 2017

- Published11 November 2017

- Published26 October 2017