Art is everywhere, but who is looking?

- Published

Sir John Everett Millais' Ophelia in Edge Lane, Liverpool

John Singer Sargent's Gassed on display in Great Howard Street

Winifred Margaret Knights' Portrait of a Young Woman at a bus stop in Linacre Lane

Edward Burra's The Snack Bar (bottom right) competes for space with a Persil advert in Renshaw Street

Works of art have replaced adverts on 22,000 billboards, bus stops and other poster sites across the UK. How many people will stop to look?

Art is everywhere for two weeks only. The nation's favourite paintings have escaped from galleries and are on roadsides, in train and Tube stations and in shopping centres across Britain.

That is the idea behind Art Everywhere, a scheme cooked up with the art and advertising establishments, in which 22,000 commercial poster sites have been taken over by reproductions of 57 artworks.

On a wet Tuesday morning in north Liverpool, a roadside poster comes into view - a 6ft (1.8m) work of art up a pole.

The blue-black image is by James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Nocturne: Blue and Gold - Old Battersea Bridge, painted in 1872, shows a boatman in the gloom under the bridge.

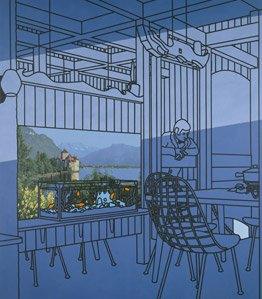

Patrick Caulfield's After Lunch, 1975, is owned by the Tate

'Quite good... I wouldn't buy it'

It is a fitting image near Bootle docks on a grey day. Beyond that is another poster, After Lunch by Patrick Caulfield, which was painted in 1975. Within his simple view of the interior of a restaurant is a picture of - or a portal to - a realistic, colourful chateau view.

In the real world, the traffic on Stanley Road splashes past. The posters overlook a storage unit and tool hire warehouse on one side of the road and a Victorian girls' institute-turned-boxing gym on the other.

"It's not very interesting, but it's all right," is the verdict on the Caulfield of one passer-by, 27-year-old Carly Louise Grimes. "It's actually quite good. It's good. I wouldn't buy it."

Ms Grimes says she likes art and goes to the city's Walker gallery "now and again".

The next person to come along, 61-year-old George Bishop, also says he likes his art, especially Monet and Hockney.

"I'm not too sure about that," is his reaction to the Caulfield. "That's personal choice. I don't have a problem with it. I'm quite happy to put artworks on the sides of buildings. It brightens the place up."

On the drive back towards the city centre, another artwork comes into view. It is Gassed by John Singer Sargent, which normally hangs at the Imperial War Museum but has been enlarged for a 12m (39ft) poster and exhibited beside a four-lane road.

At its base is a sign advertising charcoal, logs and cat litter. It is hard to tell whether any motorists take any notice, but nobody has stopped to gawp at its account of the aftermath of a mustard gas attack in World War I.

Allan Ramsay's Portrait of an African sits next to George Frederic Watts' Hope

These poster sites were designed to be seen from a moving vehicle, whereas that was probably not uppermost in Sargent's mind.

It merits a gawp - the detail of the wretched, blinded soldiers, with uninjured companions playing football in the camp in the background, is hard to make out as you whizz past in a car.

Glum expression

But it is raining. A roof is one definite advantage of a traditional gallery.

Moving through Liverpool, the artworks occasionally appear around corners, although they would be easy to miss if you were not looking for them.

Winifred Margaret Knights' Portrait of a Young Woman (1920) is on the side of a bus stop. Her hair and clothes mark her out as being from a different age, but her glum expression would not be out of place among those sheltering from the downpour.

On the southern edge of the city, Gassed looms over another main road before more raised posters appear beside a row of car dealerships.

Whistlejacket is a portrait of a famous 18th Century racehorse by George Stubbs, a son of Liverpool. Further along, Portrait of an African dates from the same era and is attributed to Allan Ramsay.

Ramsay campaigned for an end to slavery, and the painting's (probably accidental) siting next to the docks of Liverpool, once Europe's biggest slave port, gives it extra potency.

A short distance down the road, David Hockney's A Bigger Splash adorns another bus stop.

David Hockney makes A Bigger Splash on a bus stop in Sefton Street

Waiting at the bus stop, 26-year-old Joseph Dagnall is on his way for an interview with the Royal Marines. He says he is not into art and does not know what to think of the picture.

The organisers of Art Everywhere hope the project may tempt new people into galleries. But Mr Dagnall shakes his head when asked whether this image would persuade him to go to the forthcoming Hockney exhibition at the Walker.

Attention-grabbing gimmicks

Asked how it compares with images that usually appear on bus stops, he points out that Hockney is in competition with normal adverts that are still dotted around. "It just blends in," he says. "The first thing that grabs your attention [with an ad] is the text.

"If you look at that," he says, pointing to an ad for a fast-food chain on a bus stop over the road, "there's lots of information on it. But when you're looking at this, it's just an image."

That is not a criticism, just an observation that people are less likely to notice a poster unless it grabs them by the lapels. That rings true later when I seek out more art in the city centre.

Edward Burra's The Snack Bar is visible for precisely six seconds at a time

The only works I find are two side-by-side on bus stop panels.

There is Stubbs' equine portrait again, and Edward Burra's The Snack Bar. But there are four or five ads in each panel, with the images changing precisely every six seconds. Burra and Stubbs are sharing space with Persil, McDonald's and Sky.

Even if anyone were taking any notice of them - which they are not - six seconds is barely long enough to register what they are, let alone appreciate them as works of art.

And that is the problem when art is in a space normally reserved for advertising. It must compete with all the other ads, with their increasingly sophisticated moving images and other attention-grabbing gimmicks.

The art does not stand a chance. On billboards and bus stops, it becomes just another thing for people to ignore.

That is not to say that Art Everywhere is not a worthwhile experiment, in the spirit of taking art to the people.

For art lovers, spotting these masterpieces in the wild is a thrill. Others will undoubtedly stop to look and marvel over the course of the next two weeks.

But while galleries are temples to art and refuges from the pace of modern life, outside their walls is a more hectic world.

- Published8 August 2013

- Published8 August 2013

- Published8 August 2013

- Published7 June 2013

- Published30 June 2013