How virtual reality may change your life

- Published

The band Miro Shot explored virtual reality with their audience in Amsterdam in May

Virtual reality (VR) is being touted as a big growth area for film-makers, engaging audiences in ways traditional film can't. But it is also being explored everywhere from rock music to psychiatric treatments. Is it all just a passing fad - or could VR really change the way we see the world about us?

In film-making it's hard to avoid talk of VR as the next big thing. A report this April claimed it could add $7bn (£5.4bn) to film-industry revenues this year and by 2021, that figure might have risen 10-fold.

However, performer-composer Roman Rappak and his new band Miro Shot are at the forefront of bringing VR to rock music.

Giant blue head

In May, Rappak premiered a VR show at the Centre for Contemporary Art in Amsterdam, funded by a Dutch grant.

Around 10 people at a time took their seats as Rappak and the other musicians stood ready to perform on stage. Before a note of his composition Lifeforms was played, audience members were helped into VR headsets through which they experienced a performance of around eight minutes.

The band became graphic versions of themselves before the audience was suddenly flying over an empty landscape and then a giant blue head of a woman emerged.

The show is designed to appeal to every sense: Electric fans wafted specially-concocted fragrances over the audience. Some people were quicker than others to work out that the event is 360 degrees: It's a good idea to look up or down and turn to see what's behind you.

Rappak says VR intensifies the usual concert experience.

"It's everything that's exciting about a concert but more intense. There are the colours, the sense of place, the aromas, the beats. If you're at a gig and love it that will transform you. With virtual reality it's magnified."

Rappak is impressively ahead of the game in his ambitions for VR and music - but some non-performance uses are surprisingly well-established.

Prof Daniel Freeman of the University of Oxford says using VR to treat anxiety disorders goes back to the early 1990s.

"VR has the potential to revolutionise how we treat certain mental health problems and phobias," he says.

"Many of the problems are linked to our environment in some way, such as a fear of enclosed spaces. With virtual reality we can now put people in the physical situation which disturbs them. Then we coach them in the best way to overcome these anxieties."

Visiting Europe's largest permanent virtual reality facility

Prof Freeman says VR could potentially help people deal with conditions like acrophobia (fear of heights) and even depression.

"Therapists have been using VR to treat patients with claustrophobia," he explains. "We can use a headset gradually to populate a lift, allowing the patient to control their tension level. What we're working on in Oxford is a programme which doesn't even require a therapist to be there. VR could bring the benefits of therapy to more people.

"With depression, therapy would for now probably complement evidence-based treatment with a skilled therapist. But VR can certainly help people re-engage with the world and be stimulated by it."

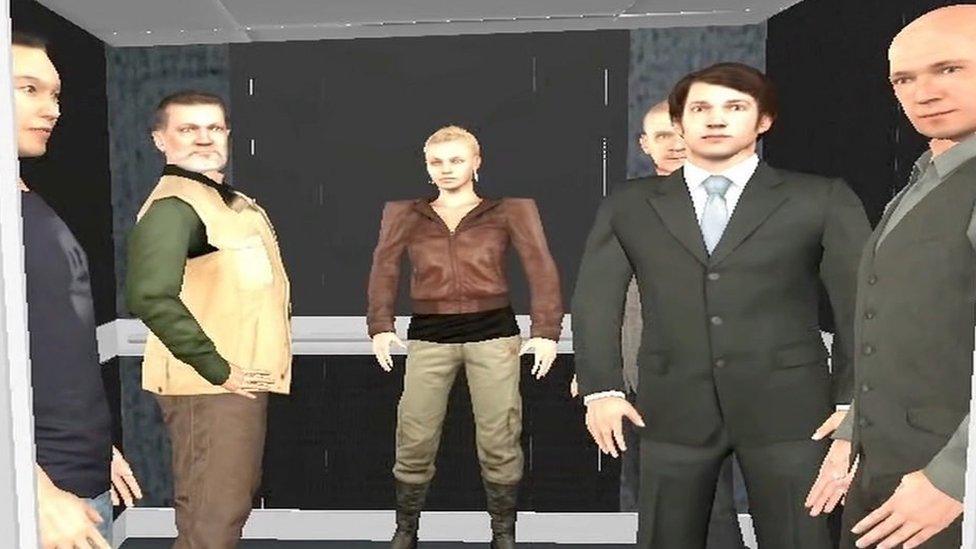

Virtual reality people in a lift

The VR recreations were of everyday situations. A London Tube train and a lift could each be made more or less crowded in a carefully controlled experiment.

"There's still research to be done but for certain patients the potential benefits are great."

If clinical psychologists were quick off the mark, journalism is coming late to the VR party. Zillah Watson of the BBC has just written a report for the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism called VR for News: The New Reality?, external

"The Reuters Institute was keen to cut through some of the hype about VR and ask some difficult questions: How can VR ever be monetised for news and how compelling is it currently for audiences?" she says.

"What really got newsrooms excited was when, in November 2015, the New York Times decided it was getting into VR and launched an app.

"The newspaper wanted to discover new and exciting ways to tell stories. VR compels you to think in a completely different way about journalism which has to be a good thing - but the practicalities are complicated."

Watson says there are problems even with what is meant by VR. "Full VR - at least at this stage - involves putting on a headset which is tracked and, as you look around, the scene you see is rendered in real time and you feel you are there.

"For now, what is branded VR in news is in fact largely 360 video which people watch on their computer screen or on a phone. People watching news basically don't want to put on a headset. It's a problem - though technology will develop."

Notes on Blindness was released in 2016

Watson thinks the best VR material available is often at the features end of the news spectrum.

"A fantastic piece to seek out is Notes on Blindness, which isn't hard news at all. It illustrated the audio diaries of the academic John Hull who, in the 1980s, had to come to terms with blindness.

"Virtual reality is a challenge for TV news where traditionally it's assumed a story is mediated through the reporter. But if an editor wants to hear from refugees somewhere, then for VR it could work just as well - or better - if the refugees tell their own stories."

Watson says journalistic VR is in a fusion period. "Virtual reality is taking baby steps and no one yet is sure what the public demand is."

'Storytelling mechanism'

Toby Coffey, head of digital development at London's National Theatre, is convinced that VR will become part of what its audience expects.

"Twenty-two years ago I wrote a dissertation about virtual reality in the treatment of repeat offenders - so it's all older than people think," he says.

"But about four years ago it was clear modern VR was becoming important and when Rufus Norris arrived to run the National he wanted to explore it as a storytelling mechanism."

The theatre had rave reviews this year when it co-presented the VR piece Draw Me Close at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York.

Written by Jordan Tannahill, it's an extraordinary one-on-one piece where the viewer - wearing a headset - moves through a physical set of a child's bedroom and interacts with what may be a memory of Tannahill's own mother.

The mother is played by an actress in a motion-capture suit (which means purists would say the piece isn't VR but augmented reality).

Draw Me Close involves an actress in a motion capture suit who interacts with you live

Coffey says he still doesn't know what the National will offer in terms of VR. "Like everyone, we're feeling our way and we're still not at the mass adoption stage.

"I'm looking forward to when someone will buy a National Theatre ticket and VR will be a major part of the experience. But I can't say if it will physically be in one of the National Theatre auditoriums.

"There's one-on-one storytelling, such as Draw Me Close, but also there's social VR. That can be where a group of people wear individual headsets and see the same thing but are cut off from everyone else.

"Or there's what I call social social VR, where people are aware of one another even with the headset on and that's really what I'm looking at."

Almost everyone in VR talks of how quickly technology is changing and how ambitions are changing too.

Rappak says a huge part of the attraction of VR is that for now, nothing is certain.

"In 2017, VR is about a headset which you strap to your skull. But a couple of years from now it could be glasses or some new kind of contact lens. It's important not to get obsessed with the technology because the one certainty is it will change within months.

"There's lots being written about virtual reality and I'm sure some predictions will prove completely wrong. But VR is almost totally unexplored which is why it's an amazing opportunity."

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published26 June 2017

- Published3 February 2017

- Published5 May 2016

- Published11 November 2016

- Published18 May 2016