Viewpoint: Does deafness contribute to dementia?

- Published

Recent scientific research has suggested there could be a connection between hearing loss and the brain, contributing to greater cognitive decline as we age.

More people suffer problems with their hearing than any of the other senses. Whether the reasons are genetic, caused by exposure to damaging levels of sound, or simply growing older, about one in seven people in the UK suffer some form of hearing disorder.

Such hearing impairment often causes communication problems in social situations, but can also result in disadvantages in education, employment and even earning potential.

According to 2005 estimates by the World Health Organization (WHO), about five million people worldwide are suffering from profound hearing loss, and 50% of all people over 65 are affected by age-related hearing loss (presbycusis).

Presbycusis is set to increase significantly over the next 20-30 years as the population ages. Prof Adrian Davis, of the British MRC Institute of Hearing Research, predicts that approximately 100 million Europeans will be hearing impaired by 2025, external.

We know that some forms of hearing loss can be prevented, and that the early diagnosis (through universal new-born hearing screening), treatment and management of hearing loss in children lead to major improvements in life outcomes.

Exposure to workplace noise in places like factories is falling in modern societies, yet hearing loss is expected to increase in prevalence and impact over the next decade. One reason is a rise in exposure to social noise.

This sort of noise tends to be unregulated and the lifestyle choices we make - such as wearing headphones, especially when travelling on noisy public transport where we tend to crank up the volume - are likely to impact on our future aural health.

'Social stigma'

The perceived social stigma of wearing a hearing aid - usually associated with old age - is believed to be off-putting for many. Add in the fact that the treatments available for hearing loss - hearing aids and cochlear implants - do not restore normal hearing mean that fewer than 15% of people in the US who would benefit from wearing a hearing aid are using one, external. The figures are believed to be similar in the UK - leaving the vast majority of those with hearing problems suffering in silence.

An estimated 10 million people in the UK have some form of hearing loss

As difficult as it can be for those who struggle to follow conversations in social situations, the problems could be more serious. Recent research suggests that if left untreated, hearing loss might contribute to an acceleration in cognitive decline - relating to our understanding, reasoning and perception skills - as we age.

In a recent study of the cognitive abilities of those in their 60s, Prof Frank Lin, from the Centre on Ageing and Health at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, found that after adjusting for factors that might influence performance on cognitive tasks - socio-economic background, education attainment or medical history, for instance, and excluding those with moderate or severe deafness, participants with greater hearing loss showed poorer scores on standard cognition tests, external.

The reduction in performance on these tasks associated with a 25-decibel hearing loss (classified as "mild") was equivalent to an ageing effect of seven years in cognitive abilities.

Whether hearing loss is truly a cause of cognitive decline or merely a risk factor associated with the ageing brain, the decline of cognitive abilities into dementia is set to explode financial models of health and social care in Western societies and requires urgent attention.

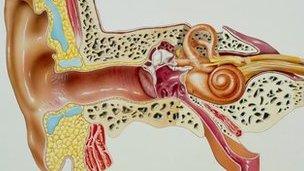

More direct evidence from studies of experiments with animals and humans, however, suggests that we may have to alter the very concept of what we mean by hearing loss, and that current tests - particularly pure-tone audiometry which measures our ability to perform "pin-drop" hearing - may not be sufficient to pick up the early signs of a decline in hearing function.

A recent study of mice exposed to two hours of "disco" noise, for example, revealed temporarily-reduced hearing sensitivity, of the type experienced following a loud party or after visiting a club. Several weeks later, although hearing sensitivity had recovered to normal levels, activity in the auditory nerve connecting the inner ear to the brain remained impaired.

This was particularly noticeable over the range of sound levels associated with everyday tasks, external such as listening to the television or chatting at the dinner table.

Such "hidden" hearing loss, not evident in the audiogram (a test that measures hearing sensitivity), is also apparent in human listeners who experience persistent tinnitus, but otherwise normal sensitivity, external. This suggests tinnitus might be just one manifestation of a hearing problem associated with everyday tasks.

Together, the evidence suggests that, left undiagnosed and untreated, deafness and other hearing problems will have an increasingly detrimental impact on the well-being of individuals and society at large for some time to come.

- Published12 September 2012

- Published6 February 2012

- Published5 July 2012

- Published20 June 2012

- Published21 November 2012