Medieval skeletons give clues to leprosy origins

- Published

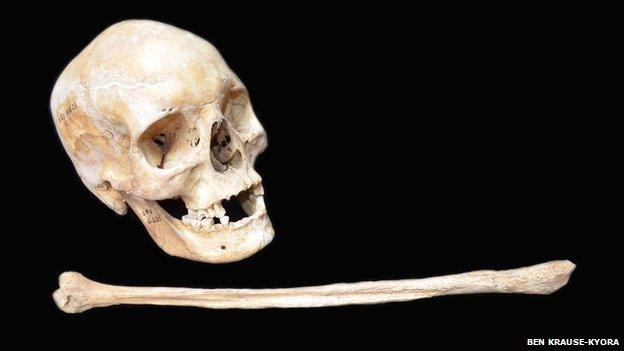

As part of their study, scientists extracted DNA from skeletons that were 1,000 years old

The genetic code of leprosy-causing bacteria from 1,000-year-old skeletons has been laid bare.

Similarities between these old strains of the bug and those prevalent today have given scientists unique insights into the spread of the disease.

It has revealed, for example, the key role played by the medieval Crusades in moving the pathogen across the globe.

The researchers tell Science magazine, external they hope their study will lead them to the ancient origins of the leprosy.

In medieval times, a sufferer of leprosy was likely to be an outcast, secluded from society in quarantined colonies. Then as now, there was a social stigma with having the disease, but it can be cured if caught early. If left untreated, it can leave sufferers deformed and crippled.

The scientists in this new study compared the genetics of the disease-causing bacterium Mycobacterium leprae found in five medieval skeletons from Europe with 11 modern strains.

The DNA comparison showed that one type of leprosy found in Europe 1,000 years ago is the same as one present in the Middle East now.

This strengthened the view that the disease spread during the Crusades, said Johannes Krause, from the University of Tübingen, Germany, one of the authors of the work. This was a period when Christian armies fought for control of what they called the Holy Land.

It remains unclear which direction the disease spread, but "lines of evidence suggest an Asian origin of the disease", as the earliest evidence of leprosy comes from a 4,000-year old skeleton found in India, external.

"This skeleton can only tell us it was present in Asia around 4,000 years ago, but we do not know where the origin of the disease is," Prof Krause told BBC News.

Another of the medieval strains is similar to one found in the Americas today. This suggests the disease was not something the first American settlers carried with them when they originally migrated from Asia, but is a more recent development that was probably introduced when Europeans colonised the continent, added Prof Krause.

"One really surprising finding was that the DNA was so well preserved, better than any ancient DNA I have ever studied," he said.

"This opens up the possibility to study the evolution of the disease in much older remains, to understand how it evolved and adapted to humans."

The medieval remains were taken from graves in the UK, Denmark and Sweden

Leprosy infections in Europe today are minimal as an estimated 95% of the population have developed immunity, but globally leprosy remains a significant problem with 225,000 new cases recorded annually

"The bacterium is still pathogenic, the same way it was 1,000 years ago, but our social conditions have changed and we have much better medical treatment. But at the same time, it's still a very prevalent disease," said Prof Krause.

Leprosy was endemic in Europe until it almost disappeared in the 16th Century, explained another member of the research team, Stewart Cole from the Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne in Switzerland, (EPFL).

"It's been proposed that [bubonic plague ("Black Death")] killed off a large part of the European population, including those suffering from leprosy.

"One of the interesting things about this paper is that the medieval and current strains are the same, whereas leprosy disappeared fairly rapidly from Europe.

"It's clear that leprosy has created a strong selective pressure on the immune system. The European Caucasian populations have acquired resistance to leprosy, they have certain characteristic mutations in genes that make them less susceptible," Prof Cole told BBC News.

Helen Donoghue, from University College London, UK, was not part of the team. She said the study of old skeletons was invaluable in understanding the origins and the evolution of disease.

"We can understand how people with leprosy lived in the past by traditional archaeological and anthropological methods, such as evidence of stigma by having separate burial sites; looking at movement of people by stable isotope analysis and using historical records for the use of leprosy hospitals and seeing who cared for them.

"The beauty of studying the DNA from ancient diseases is that it enables direct comparison of the genetic composition of past and present genomes.

"This provides direct calibration of the timescale for changes over time and enables us to look at the evolution of the pathogenic organism in relation to its human host."

- Published10 June 2013

- Published27 April 2013

- Published26 April 2013

- Published2 June 2012

- Published25 November 2011

- Published12 October 2011