Saving lives on the Ebola front line in West Africa

- Published

Baby Marian has tested negative for Ebola, her brother (left) has recovered from the fever

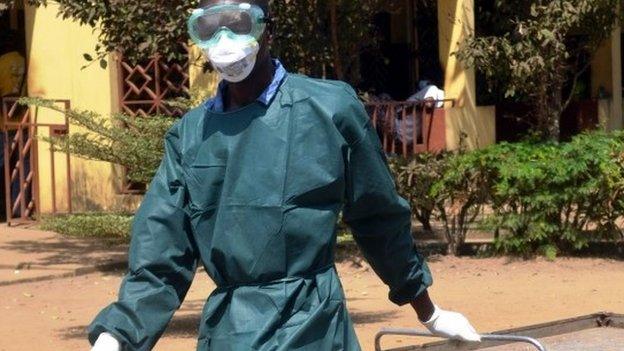

We arrive at the Ebola Treatment Centre in the forested town of Gueckedou in South East Guinea to a grim scene.

A tiny bundle is wrapped in white plastic sheeting, and stone-faced men are loading yellow disinfectant cans into a pick-up truck.

We are invited to see the heart-breaking task they are about to perform.

We drive for a few minutes into the forest. When we arrive, a small hole is already prepared.

Ebola survivor: "I was asking myself whether I was going to live."

This is the final resting place of the latest victim of Ebola: a four-month-old baby boy called Faya.

He caught the virus from his mother, who died a few weeks earlier.

His is the 20th anonymous grave in this dark and lonely clearing.

"I was there with him just before he died," says Adele Millimouno, a Medicines Sans Frontieres (MSF) nurse recruited from a nearby village.

"I had been feeding him milk. I stepped away, just for a short break, but then I was called back and he was dead. I was totally devastated."

Villagers had to bury a four-month-old victim of the disease

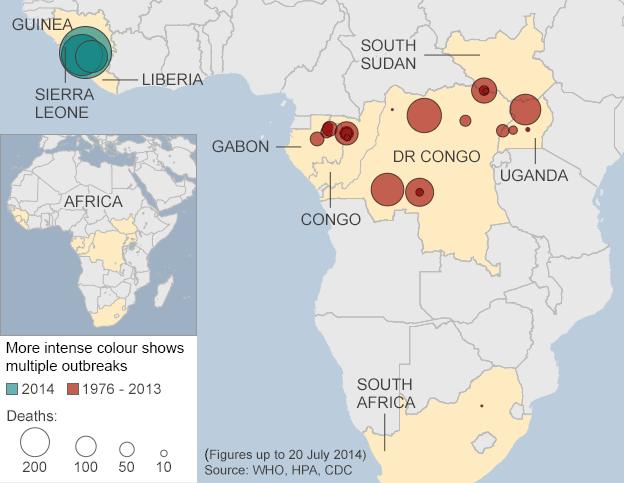

This is just another day on the front line of the latest Ebola outbreak. Gueckedou was where the first case of the disease was reported in March.

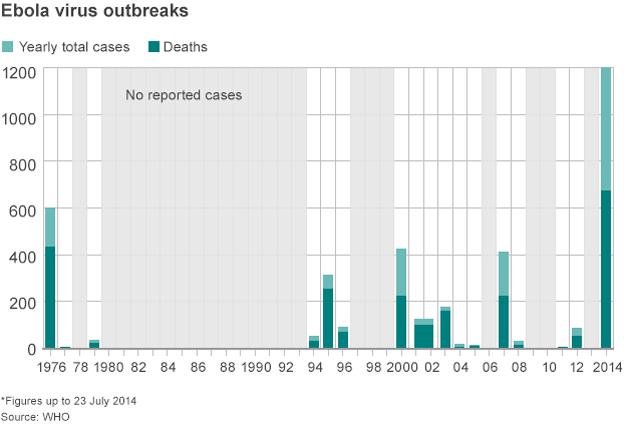

Medical charities dealing with what is now the worst Ebola outbreak in history say they expect the crisis to continue until at least the end of the year.

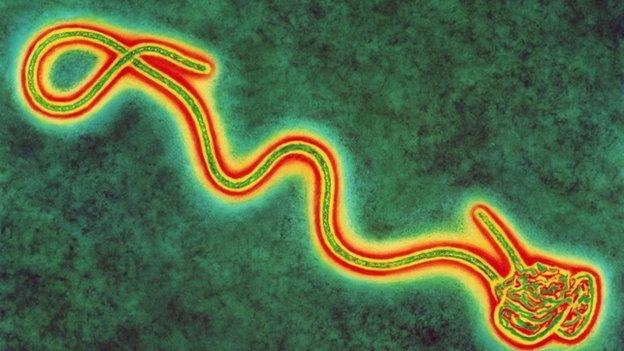

More than 670 people have died from Ebola in West Africa.

Last week Nigeria became the fourth country to confirm a death from the deadly virus.

Medicines Sans Frontieres and the International Federation of the Red Cross, which between them have almost 400 international staff fighting the outbreak, say the situation across West Africa remains out of control.

A treatment centre in Gueckedou, run by MSF, had - until 22 July - treated 152 Ebola patients, of which 111 have died.

It is the survivors that Adele says give her the strength to continue this harrowing work.

"I muster the courage to come and work here to help save my community.

"I feel very proud of our work. We have been able to save around 40 people."

The next morning we drive in a convoy with health officials to a village 12km away called Kollobengou.

The last time health workers tried to get into this village they were attacked and told not to come back.

At the scene: Healthcare worker Adele Millimouno

"Lots of people died in front of me. It was a very difficult time for me especially when the young children died. Sometimes I went outside and cried.

"Some people before they die, we hold their hands, we touch their heads, we sit by them for a little while."

Many believed medics were actually bringing the virus into communities, and harvesting organs from the dead.

Others who did believe the virus existed were too scared to get help.

Now, after negotiations with community leaders - and another death in the village overnight - they have agreed to allow medics in.

As we enter, the fear is palpable. Residents slowly come out of their huts and congregate in the centre of the village.

The local ministry of health official in charge of co-ordinating the fight against the virus stands up and urges people not to be afraid and to allow health workers to ask them questions and assess people who could be sick.

Children try to put on a brave face in Gueckedou

They also distribute soap and chlorine. The virus is killed off easily if people maintain good personal hygiene.

But as one resident pointed out: "How can we wash all the time if we have no clean water to wash with?"

Eventually, two families bring out two very sick relatives. They are quickly taken away to the treatment centre.

Health workers were already aware of four deaths from Ebola in the village. It emerges that there have been three more.

A total of 48 others have had close contact with Ebola victims. They will now have to be monitored every day for the three-week incubation period to check they don't develop the illness.

There are still two villages in Gueckedou which are not allowing health workers in. This is a huge improvement from a couple of months ago when 28 villages were resisting help - but it is still a major concern.

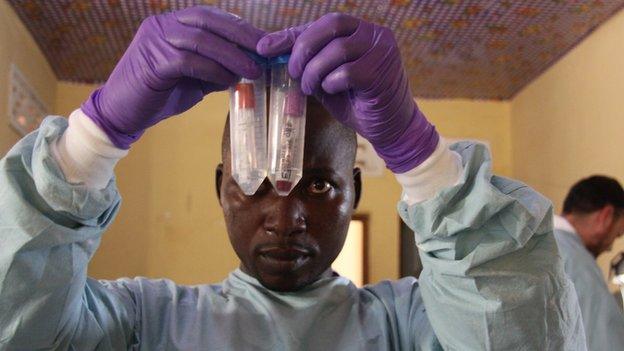

Tulip Mazumdar takes a look around a makeshift laboratory trying to battle the outbreak

Tarik Jasarevic, from the World Health Organization, says unclear messages from health workers about the virus at the start of the outbreak is partly to blame for villages closing their doors.

"People heard there is no vaccine or treatment for Ebola so many thought 'why would we go to a treatment centre if there is no treatment?'

"Then people who did eventually go, some of them died. So there was a perception that if you are taken from your village it means a certain death.

Health workers had to win the trust of the community

"We didn't put enough emphasis on the fact there are survivors and the sooner you go to the treatment centre the better chance you have of surviving, and you are not risking the health of your family. Because those taking care of sick people are exposed the most."

Dr Abdurahman Batchili is the Ebola outbreak co-ordinator for the ministry of health in Gueckedou and the surrounding forest region.

He said the situation had improved with fewer patients registered each day.

"The population is starting to be aware of the dangers of this outbreak. We hope with this momentum that in one or two months at the latest, we will end this outbreak.

"However at our borders, there is a critical situation in countries such as Sierra Leone so we have to remain vigilant along our borders."

In three days to 23 July there were 71 new cases in Sierra Leone and 25 in Liberia, compared to 12 in Guinea.

Each week thousands of people pass between the many hundreds of kilometres of the border that Guinea shares with Sierra Leone and Liberia, but there are only 13 Ebola screening posts along its length.

WHO: West Africa Ebola outbreak figures as of 27 July

Guinea - 319 deaths, 427 cases

Liberia - 129 deaths, 249 cases

Sierra Leone - 224 deaths, 525 cases

Medical charities say hope that the latest outbreak will be over soon is unrealistic.

Antoine Gauge, head of the MSF emergency response in Guinea, says: "We are very sceptical that the outbreak will be done by the end of the year.

"Ebola has no limits between borders. People here are travelling, they have family in Sierra Leone and Liberia. For sure in Guinea, we are at a more advanced stage of the response, but we can't say there will be no cases here soon."

It's visiting time back at the treatment centre and 13-year-old Alfonz - himself an Ebola survivor after getting treatment early - has come to see his little sister, Marian.

A nearby WHO laboratory carries out testing of samples

He watches her on the other side of an orange plastic barrier. He is not allowed to touch her. Instead, she is held by a health worker kitted up in a full biohazard suit.

It's good news though, initial tests for Marian have come back negative.

But Ebola is a cruel and indiscriminate virus.

The children's mother is sick, and may not survive.

As this crisis rages on, there will, sadly, be many more stories like hers.

Follow @tulipmazumdar on Twitter.

- Published28 July 2014

- Published1 April 2014

- Published8 October 2014

- Published13 November 2014